Since the birth of our daughter in May, I’ve been thinking about the village that it will supposedly take to raise her. I’m curious about where - or what - that village is today.

A meme I saw on social media depicted Tom Hanks in his role in the film Castaway, edited so that instead of being alone on a desert island, he was walking through an empty city shouting:

“IS ANYONE OUT THERE?”.

The creator, a mother, had added a caption:

“Me trying to find the village that was supposed to help me raise my children”.

I clicked on the comments - there were hundreds of responses of all kinds:

“Hyper independence is a narrative that is pushed on mothers” / “the world our grandparents and parents grew up in no longer exists” / “our lives are too busy” / “there is no village” / “the village is there but it takes work / “I struggle with ‘it takes a village, because for those of us who don’t have one, it highlights feelings of isolation” / “loneliness and isolation are a reality of our modern way of living, mothers especially feel this”.

It seemed that other mothers were thinking about their village – or lack of it - too.

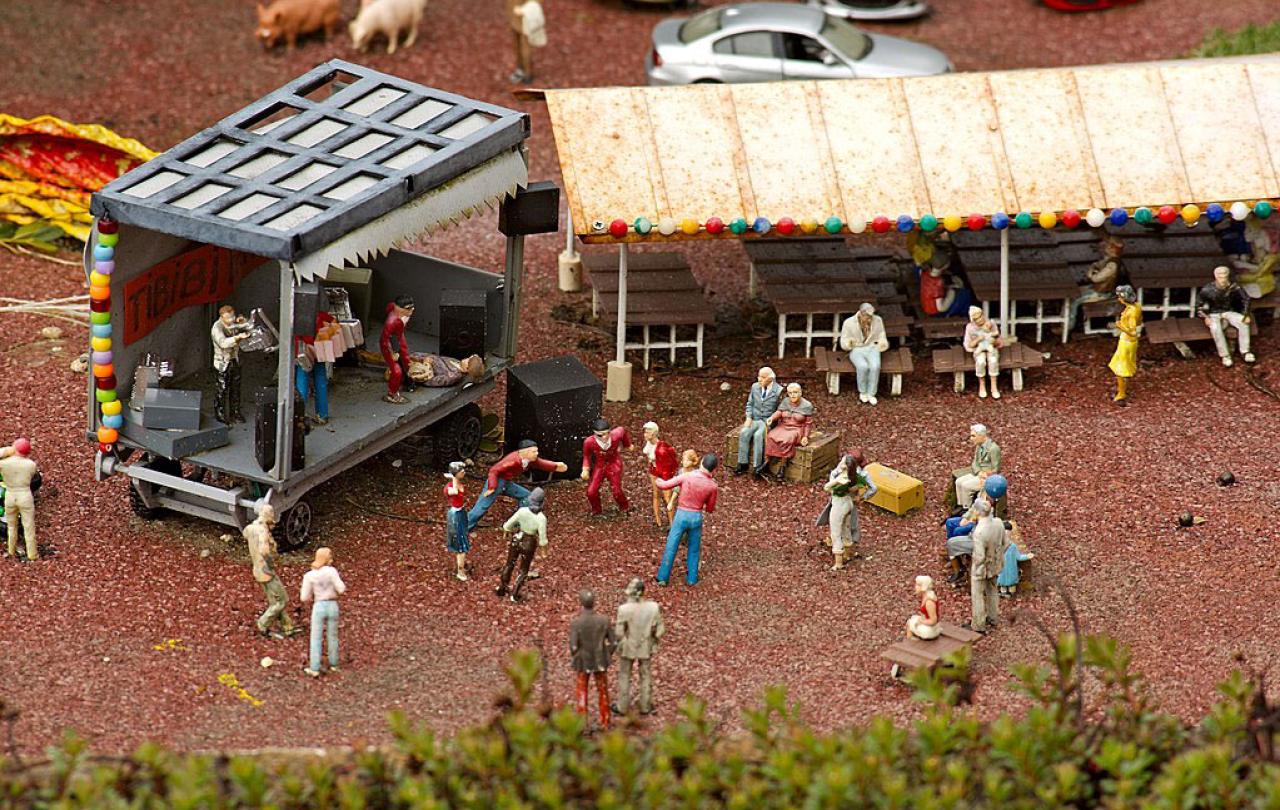

My husband and daughter and I live in an actual village in rural Devon. In the summer, we went out into the garden, and - hearing a noise from the back of the house - turned to see one of our neighbours at the top of a ladder fixing a broken roof tile. Another neighbour was standing at the bottom of the ladder holding it in place. We hadn’t asked them to fix it - we’d only mentioned needing a new roof tile in passing. My heart swelled. Though not directly caring for our young daughter, they were easing the load by caring in the way they knew how.

Online community is vital for me, and it is also lacking. Physical local community is vital for me, and it is also lacking.

That act of neighbourliness made me wonder whether the village that will help raise our daughter is the literal village we live in. Here, there are people who care for this place and the people in it. Here, there is soil into which I can plunge my hands, anchoring me in this time, this place, amongst these people, all of it working to create a web of interdependence and care which I hope will steady us all in the face of a burning and unknowable future. But we’ve only been here a couple of years, and our stories don’t yet intertwine with the roots of the place. That takes time, and interdependence takes my little family being the village for others as well as benefitting from it. And there are days when I feel I have little capacity to reach out to others.

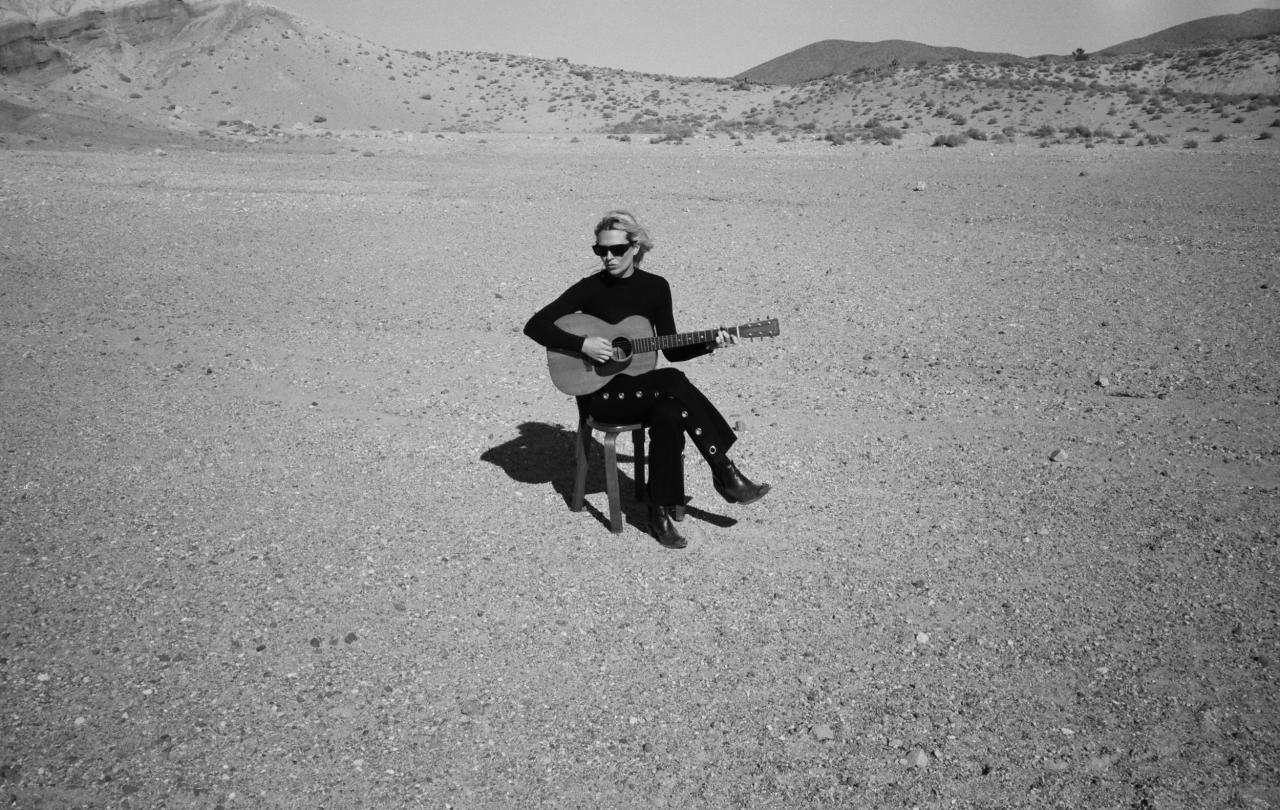

Living in a small rural village can also be hard. A welcome is not guaranteed, relationships often have to bridge real difference. And whilst historically the village was a physical place with clear edges, family roots, and familiar neighbours, that’s now not most people’s reality. My husband and I have lived in various places over the years, our scattered friends part of our journey still, even at a geographic distance. Whether or not a scattered village is possible, it knows me in a way that our local village does not and perhaps cannot. It is part of a social fabric that will weave around our daughter, despite not being immediately accessible day to day.

Or perhaps the village is increasingly virtual, made up of likeminded connections we draw near to online. Here I find not hands-on help, but understanding, ideas, encouragement, and a sense of possibility, even amongst people that don’t know me especially well. I find sustenance here, but I also know I close off real life encounters - and a more nuanced and unfiltered understanding of the world, of difference, of community - by investing in self-selecting online communities. And I want my daughter to encounter difference, to know that people can love and be loved even when they are nothing like her.

Online community is vital for me, and it is also lacking. Physical local community is vital for me, and it is also lacking.

They invite me to wonder but also to ‘think little’ as farmer and author Wendell Berry advocates, at the scale of this person, this relationship, this place.

And so I wonder what the village is, what it is becoming, and how we find it. Because whilst we’re told it takes a village to raise a child, in practice we often move to follow jobs, we live in isolated units and hear messaging that praises individualism and self-sufficiency and being able to do and have it all. And it can be as hard to call on the village as to find it in the first place - it can even be hard to accept the help of the village when it’s right there offering itself to us, so strong is the pull to look like we’re holding it all together, or to not burden others (I say this from experience). So we carry on trying to do it all ourselves.

I find myself turning to ancient things for guidance. The Christian idea of communion – a table, bread, and wine shared in community – is beautiful to me, both in how it is practiced and what it represents. Bread and wine grow and are consumed in a particular place, at a particular time. The community that shares it is knowable, together at this particular time in the world. That this entrance into faith depends so much on place and time feels significant. Communion could easily be a mystical, cerebral, hard-to-grasp idea. But crucially it’s also personal, accessible, locatable. And church - not the idea or the institution but the local gathering place - can be a place where we find this access too, as can gardens and fields and food; tethers that remind us of this created earthy peopled world. To me, these things call me back to living here and now. They invite me to wonder but also to ‘think little’ as farmer and author Wendell Berry advocates, at the scale of this person, this relationship, this place. There is a tendency to think big when it comes to solutions to world crises when perhaps thinking little - at the scale of the ‘village’ - is more actionable, more sustainable, more appropriate – a solution that works here might not work there, and that’s ok. Berry says in multiple thoughtful ways that ‘what we stand on is what we stand for’. His is a call to know place, to invest in place, to be in place, despite (and perhaps because of) the challenges that come with doing so.

I think the local is going to become more important - calling us to find our way back to community in a time of division and overwhelming global challenges.

‘Thinking little’ might happen in a street, a church, a garden, a neighbourhood. A place where we can root into literal or metaphorical soil, where isolation can turn to relation, where interdependence becomes easier to live out. It need not be an either/or between this and geographically distant or online communities though - I think online spaces offer their own care in the world as it is. But the communion table shows me hospitality as well as mystery, and Jesus – whose body communion draws us closer to – shows us a truth built locally, relationship-by-relationship. It calls us to the challenge and beauty of caring and being cared for in our own here and now.

Perhaps the early Christians had it right by being deeply invested in place, and in something beyond place too. They lived locally whilst acting globally and spiritually, ready to leave if the call should come. They were ready to build the church, person by person into something whole. God, after all, calls us to be a collective, to love our neighbours and in return, to feel love. I think the local is going to become more important - calling us to find our way back to community in a time of division and overwhelming global challenges, when faceless corporations would rather we relied on them than each other. As part of that, I think it’ll become important to engage with local civic bodies too, to all feel able to take part in placemaking and decision-making, especially when national government seems increasingly out of touch (my time as a District Councillor has given me a whole new lens on what living locally means).

Working out what the village might mean – as a mother, a citizen, a neighbour – as our daughter grows is an ongoing journey and it’s a theme I’ll return to here. But what I know is this: that I want us to be part of an ecology of care. I want us to offer and more graciously receive that care. I want us to be like the trees outside my window: linked together, rooted in place whilst reaching upwards and outwards to the light that is sometimes hard to see, but is always there.