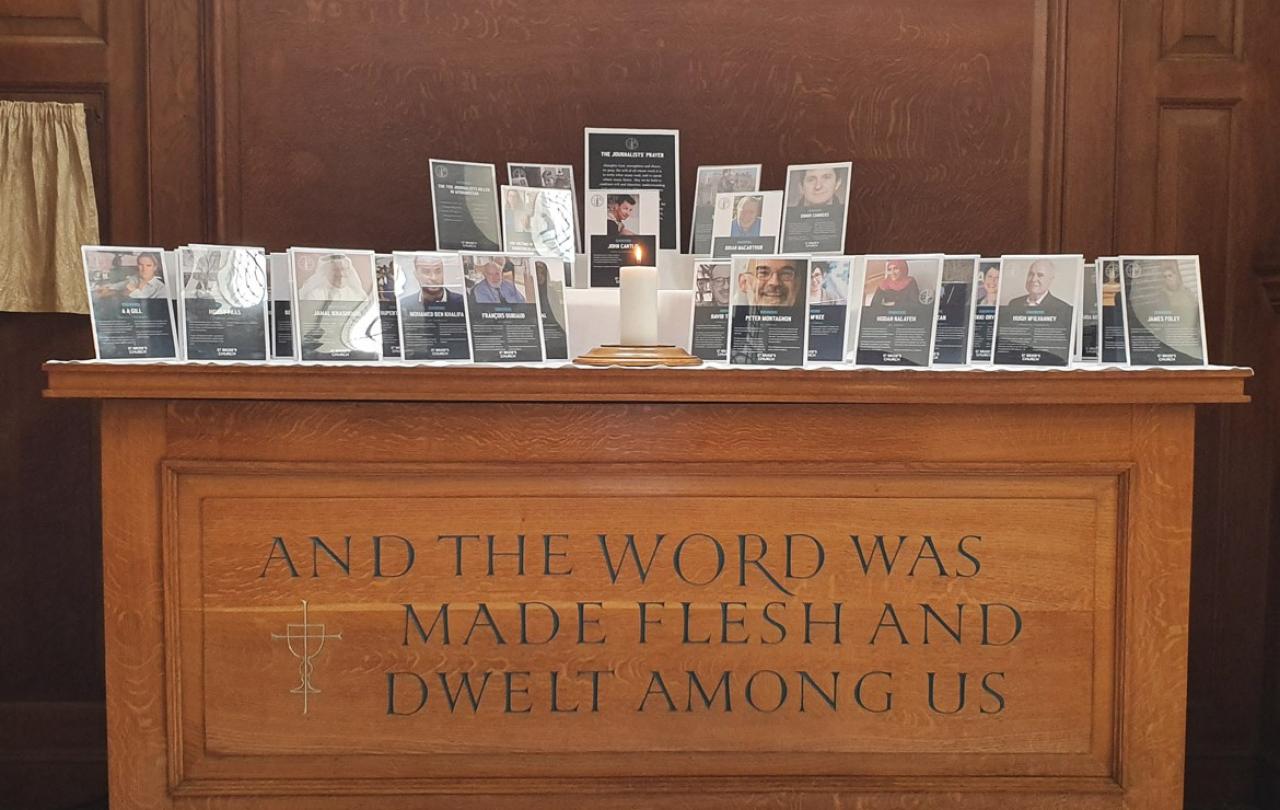

The Journalists’ Altar at St Bride’s church, on London’s Fleet Street, bears the Perspex tombstones of reporters and their colleagues who have died in wars and conflicts around the globe, in the act of bringing news to us.

This solemn memorial is joined by new ‘stones’s for Anas al-Sharif and his four-man crew from Qatar-based al-Jazeera, who were killed in a targeted strike on their tents at the gates of the Al-Shifa hospital in eastern Gaza City.

It was worth checking that they’re included on the altar, as there’s the sneaking suspicion that someone might have decided that honouring them in this way would be inappropriate or even inflammatory. The Israel Defence Forces (IDF), who killed them, would certainly take this view, having described al-Sharif, one of the few television correspondents bravely to have remained in northern Gaza, as a “terrorist” who “posed as a journalist.”

Journalist rights groups, such as the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), as well as, unsurprisingly, Al Jazeera itself counter that this is baseless. The CPJ adds “there is no justification for [the] killing.”

Of course there isn’t. Al Jazeera is pro-Arab and consequently pro-Islam and, therefore, anti-Israel. Al-Sharif may have had links with Hamas in the past, but he and his colleagues were demonstrably non-combatant. If we start killing journalists who are biased against us, we’re entering very dark moral territory indeed.

I worked for The Observer when it was owned by conglomorate Lonrho and it promoted proprietor Tiny Rowland’s best interests in Africa and in his battle with Mohammed Al-Fayed for ownership of Harrods. News Corporation’s titles aren’t famous for exposing and criticising the activities and opinions of the Murdoch family.

It might be a stretch for even their fiercest critics to suggest that Rowland or the Murdochs had committed acts of terrorism, but the point is that journalism, good or bad, is never truly independent. That al-Sharif and his friends had associations with Hamas is largely irrelevant. Indeed, journalists must have contacts with the dark side.

If we’re at risk for our allegiances, then it’s not just us but freedom itself that is under threat. Imagine if we could be arrested for sympathising with supporters of Palestine Action, currently a proscribed terrorist organisation in the UK. That, worryingly, begins not to sound too farfetched.

Journalism, when it works properly, shines as a light in the world’s darkness, revealing what’s really going on. It’s what makes it a less trivial professional activity than many other walks of life. The Journalists’ Altar bears testament to that.

The light shining in darkness is central to the Christian tradition, revealed in the prose poetry of the opening sequence to John’s gospel (a line of which appears on the Journalists’ Altar). It is inextinguishable, exists only because darkness exists and is revealed in the human capacity for love, the triumph of hope over despair and lives led self-sacrificially.

That’s way too much freight for humble old journalism to carry. But it is true that journalism shines a light in human affairs, the better to reveal what lies in the darkness so that we can examine it. In that endeavour, it shares an interest in truth

A late and lamented Observer desk editor of mine once told me dolefully, when I wailed that lawyers were preventing a story I knew to be true, that “there’s your truth, there’s my truth and there’s the truth.” I don’t think he meant to mark the difference between subjective and an objective, absolute truth, but he did define the truth game that we’re in.

As it took Gaza’s territory, Israel’s government long ago ceded its moral ground – quite an achievement given the scale of the atrocities committed by Hamas on Israel’s people on 7 October 2023. It simply cannot afford to allow the light of what is true to shine in the darkness of Gaza. So, it bans foreign correspondents from reporting from within the Strip.

“Democracy dies in darkness” has been the slogan of The Washington Post since 2017, a line it lifted from its Watergate heritage. There’s been a fair bit of chortling and downright rage at this conceit since its newish proprietor, Jeff Bezos of Amazon, declined to allow the Post to back the Democrat candidate against Donald Trump at the last US election (those pesky owners again).

But it’s not really democracy that dies in the dark. It’s just that we can’t see in the dark. We need light to do that. Journalism, for all its weaknesses and absurdities, provides some of that light. Israel, Gaza and the deaths of five Al Jazeera journalists show that it’s a light that isn’t inextinguishable. That’s more than a worry.

Al Jazeera’s anchor Tamer Almisshal nailed it: “Israel, by killing and targeting our correspondents and team in Gaza, they want to kill the truth.” Our democracies need to ensure that doesn’t happen.

Support Seen & Unseen

Since Spring 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,500 articles. All for free.

This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief