In Pride and Prejudice, Mr Bennet has a conversation with his favourite daughter, Lizzy, about her older sister’s heartbreak. He says,

‘Your sister is crossed in love, I find. I congratulate her. Next to being married, a girl likes to be crossed a little in love now and then. It is something to think of, and it gives her a sort of distinction among her companions.’

It’s one of those lines, genius as it is, that I would hate were it not written by Jane Austen. But it was, so I don’t. I do, however, like to think that his words are outdated. His thoughts, an artefact. That such a notion may have been true when women were unable to have any kind of aspirations that transcended romantic (and not-so-romantic) attachments, but we’re definitely over that now. I sit smugly in the knowledge that Mr Bennet’s words are a jibe that I can affectionately roll my eyes at; witty, yet redundant.

At least, that’s what I did think. Now, annoyingly, I’m not so sure. What changed my mind? Well, Taylor Swift’s latest album dropped. And now I think that Austen, as usual, was onto something.

The Tortured Poets Department has broken more records than I can count, many of which were broken before it was even released. Love it or hate it (I happen to be in the love it camp), Taylor is going to make it pretty darn hard for you to ignore it. Housed within this juggernaut of an album are thirty-one songs that seek to remind us that it’s better to have loved and lost, than to have never loved at all. Thirty-one songs that offer a masterclass in melodrama. Thirty-one songs that prove Mr Bennet right.

Somewhere along the line, have we been taught that tragedy is a signifier that our love is some kind of epic thing that is happening in the universe?

Here’s the theory, the premise, the pop-culture context you need to understand this album’s intentions: ‘The Tortured Poets Department’ was/is a WhatsApp group that Swift’s past-love, Joe Alwyn, was/is a part of. And so, this album is their story; it’s the story of their relationship crumbling, their hearts breaking, their understanding of one another disintegrating. Whether the lyrics are filled with fact or fiction, it doesn’t really matter. We’re soaking it up - every reference, every hint, every clue. These tortured poets have captivated us.

Agony, tragedy, ecstasy, torment, regret: that’s the currency this album deals in. Heartbreak, I suppose. This record-shattering album is about heartbreak. And it got me thinking, why are we so obsessed with love hurting? Why are Romeo and Juliet something to aspire to? Why is tragedy some kind of signifier of ‘real’ love? Why, as Mr Bennet says, do we like being ‘crossed in love now and then’?

The key lyric that holds the first song on Taylor’s album together sums it up pretty well, as Taylor melodramatically declares – ‘I love you, it’s ruining my life’.

Firstly - no it’s not, Taylor. You’re Taylor Swift, a life less ruined no-one could find. But secondly, why is that tumultuous kind of love something to idolise? I’m genuinely wondering. Because, admittedly, I’m as guilty of this as anyone.

Maybe it’s a way in which we feel as though we’re living a meaningful story, it’s our main-character-syndrome rearing its head. Somewhere along the line, have we been taught that tragedy is a signifier that our love is some kind of epic thing that is happening in the universe? That our relationship is re-arranging the cosmos somehow? That this pain is so powerful, stories will be told of it? Afterall, many of the greatest love stories end in agony, do they not? Would we care about Titanic’s Jack and Rose, La La Land’s Mia and Sebastian, or Fleetwood Mac’s Stevie and Lindsay had they lived happily ever after? Perhaps not. If a beige life is to be avoided at all costs, the torture of heartbreak is, I suppose, a particularly vibrant shade.

Taylor’s whole album is an ode to Romanticism: its lyrics are dramatic, beautiful, grand and religious.

Or perhaps it’s a sensation thing, akin to our obsession with jumping out of airplanes or walking over hot coals. Maybe we just want to feel. And according to most psychologists, heartbreak is one of the most powerful and emotive experiences one could face – a plane could not get high enough, nor coals hot enough, to compete. The science behind it is fascinating. I truly had no idea.

Which leads me onto my second question – why don’t we care for the science of it?

Why, when it comes to explaining what we’re feeling, do we declare our ‘heart to be broken’ as opposed to ‘the right side our brain is experiencing a deeply distressing emotional sensation following a shattering of an emotional attachment, triggering feelings of loss and inadequacy’?

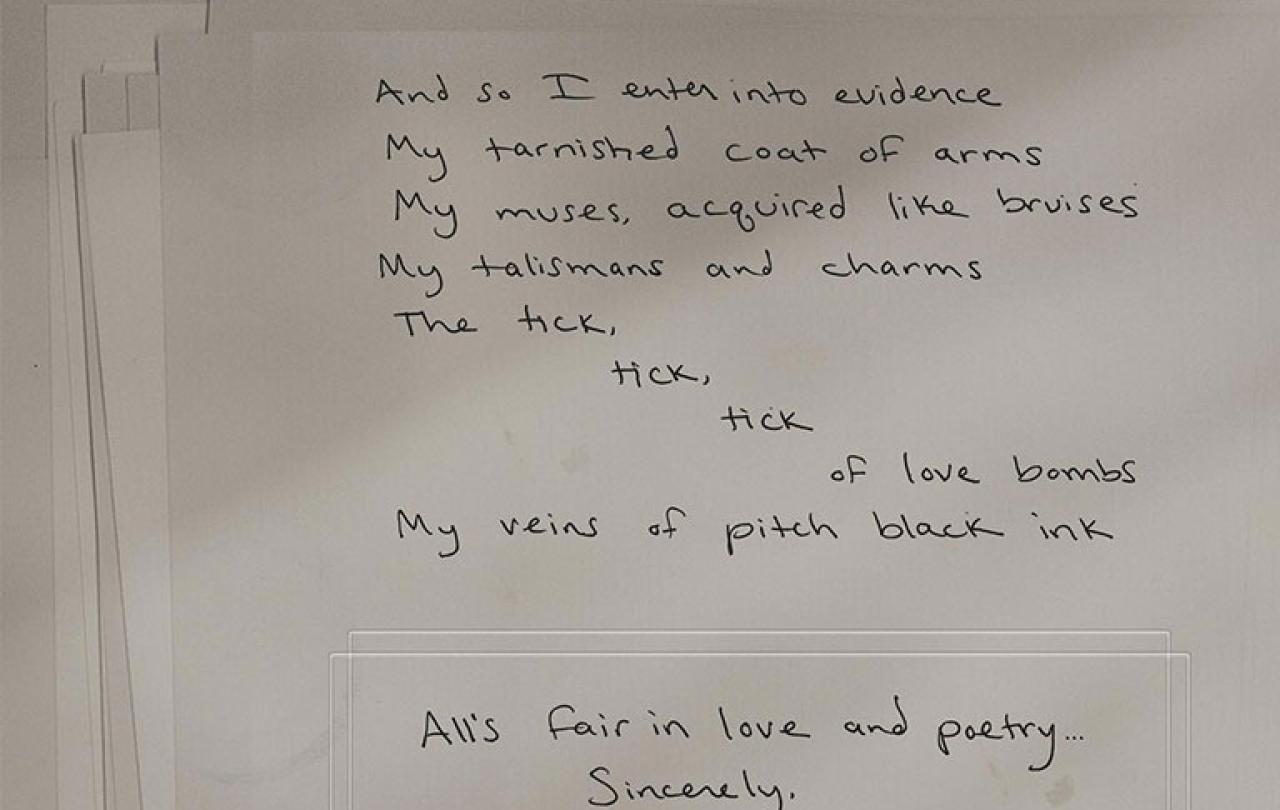

Interesting, isn’t it? How that second definition somehow feels less true. Maybe we have Romanticism to blame for that - the poets, philosophers and writers who shunned reasonable, practical, scientific language in favour of the tragic, the grand, and the sublime. Taylor’s whole album is an ode to Romanticism: its lyrics are dramatic, beautiful, grand and religious.

In her song, Guilty as Sin, Taylor writes –

What if I roll the stone away? They’re gonna crucify me anyway. What if the way you hold me is holy… I choose you and me, religiously.’

Yes, she’s comparing her crush on a man to the crucifixion of the Son of God. If this isn’t over the top, I don’t know what is. In many ways, this album knows it’s being silly, over-dramatic and naïve. But it also knows that to be those things is to be as honest as possible. It is shunning human-sized explanations of heartbreak, and is instead desperately searching for the deepest, highest, grandest language it can find - because that kind of language just feels truer. And I find it pretty fascinating that such language still has Jesus all over it.

All of it has got me thinking, we don’t really want everything controlled, measured and understood, do we? We don’t really want to be the most powerful thing we know. I think that’s a myth. A convincing one, I grant you. But one that has cracks in it. Romanticism is one such crack. School of Life says this about the Romantics, ‘Romantics don’t believe in God, but they go in search of the emotions one might find around religion’. Awe. Transcendence. Our own small-ness in the face of something great – that kind of thing.

They don’t believe in God, but they crave him. Interesting.

I think maybe that’s (at least partly) why we want our love stories, the good and the bad, to engulf us, to be something we must succumb to, to be written in the stars – predating our awareness of it and transcending our control over it. We think, at least to an extent, that love and heartbreak, they happen to us. They’re a sacred hand that we have been dealt and must grapple with. This is Romanticism - and apparently it hasn’t gone anywhere, Taylor Swift and her band of tortured poets have just proved it.

Perhaps Mr Bennet was right after all; perhaps we do have an odd thing about heartbreak. But hey, don’t blame women. Blame the Romantics and that God-shaped hole within them… and within us too, apparently.