It is two years since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, on 24 February 2022. We are still sleep-walking, with the British public and political class yet to grasp its implications. The risks of large-scale conflict have surged, and the British military is inadequately prepared for the operations it may soon be called on for. One day, swords will be turned into plowshares. But right now, in this imperfect world, we need more swords. Even if not widely enough, some have realised that the global order has changed. But fewer still are willing to act on that realisation.

The Russian assault in February 2022 was designed to shock. Repeating the plan which the Soviet Union had used in Afghanistan in December 1979, armoured columns advanced on the capital on multiple axes, preceded by an aviation assault into an airport just outside the main capital, intended to allow invading forces to ‘decapitate’ the government. The 2022 attack was also accompanied by strikes on key targets in Kyiv itself, with Russia mimicking the ‘shock and awe’ campaign with which coalition forces had initiated the invasion of Iraq in 2003.

The international situation has been parallel, with an immediate shock, galvanising intensive and often heroic action—but the resolve for which has withered with time. Some moments of demonstrated resolve among the public during the early months stand out in my memory. The students in Oxford who were fundraising not just for blankets for refugees, but for body armour, night-vision goggles and, if I remember rightly, even weapons. The stranger who bought a decrepit caravan from me for scrap saying, quietly and undemonstratively, that she would not buy fuel from Shell because it was blood oil. And, the 12-foot-tall statue in Oxford’s Broad Street of a Ukrainian soldier expressing the city’s solidarity.

This was echoed at the national level. In a welcome act of leadership, Boris Johnson, then Prime Minister, declared that Putin “must fail and must be seen to fail”. This gave the necessary direction for a series of forward-leaning policies, both economic and military, to support Ukraine.

The shock was short-lived, however, and in its place are concerning questions about both public and political resolve. The underlying issue is the significance of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. While the immediate consequences of this conflict are felt by Ukrainians, it matters more widely—to both the British and the global public. Realising these consequences, and then taking the appropriate action to address them, is now urgent. That action involves serious investment in defence industries, defence capability, and the military.

The lights on the dashboard of global security are all flashing—some amber, and some red.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine matters more widely in at least the following four ways.

First, it has incurred immediate costs on consumers globally. This sounds bland but is not. Soaring energy bills have cost lives, with the Economist estimating that the war indirectly killed more people in Europe in winter 2022 than Covid-19 did; so too do soaring food costs in countries which desperately need a steady, cheap supply of grain.

Second, the current course of the conflict in Ukraine has dramatically raised the risk of a confrontation between NATO and Russia, which may include either or both of conventional or hybrid conflict. Russia has not succeeded in turning Kyiv into a satellite state. But, unless NATO dramatically increases its supply of materiel, including high-end capabilities, the most likely outcome of the war is that Russia will successfully ‘freeze’ the conflict while controlling approximately a fifth of Ukraine, including the most economically productive part of the country in the East. Such success increases the likelihood of a revanchist Putin, seeking to establish Russian control over its claimed ‘historic’ borders and having put his economy on a war footing, attacking perhaps the Baltic states. Or Russia may simply seek to disrupt NATO countries in forms of conflict that fall short of conventional war, but risk escalation, as witness the recent Estonian arrests of ten people alleged to be part of a Russian destabilisation operation. The collective self-defence pact embodied in NATO’s Article 5 means that UK forces will be involved in any response to such aggression.

Third, the current inability for the US and Europe to act decisively, due to domestic political irresolution and polarisation, in the face of a clearly deteriorating security environment, emboldens potential adversaries. This is evident daily at the moment, with Republican politicians refusing to approve the $60 billion support package for Ukraine proposed by the Biden administration; as a result, the Ukrainian army has just withdrawn from Avdiivka, because it lacks the artillery shells to defend it. In a post-2016 timeline, and from an external perspective, the West now looks decadent.

Fourth, that Russia is likely to succeed in its war aims (unless something changes on the battlefield) further undermines the norms of non-aggression which are central to our currentrules-based international order. The domestic political trajectories of Russia, China, and Iran are not presently encouraging. All have stated goals which would see change in who controls relevant territories, and none rule out the use of force in achieving their goals.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, then, is an inflection point. The lights on the dashboard of global security are all flashing—some amber, and some red.

But Javelins do not descend ex nihilo from the clouds: they need to be manufactured by advanced industries.

In the face of such a deteriorating security environment, the urgent task for a responsible government is to ensure that it has the required military capability. This capability must be at minimum sufficient to defend its own citizens. It must also be sufficient to protect more widely those whom it has undertaken treaty commitments to defend. And, as a contribution to the wider public good, it is desirable that that capability should be sufficient to defend other innocent parties globally, subject to appropriate authorisation. Central to this capability is having a defence industry which will develop and manufacture the arms required.

The defence industry has frequently attracted criticism and controversy, with the most damaging charge being that it sells weapons to authoritarian regimes in corrupt deals. Exporting arms to regimes that will use them repressively, through corrupt contracts, is plainly wrong. But responding to this criticism does not require banning or otherwise abolishing the defence industry. Rather, the correct response is to reform it and then regulate it effectively, on the grounds that if war itself can sometimes be just, then the production of the tools required for war must itself be just.

If the state is, as St Paul had it, commissioned to punish the wrongdoer, ‘not bearing the sword in vain’, someone must make the swords.

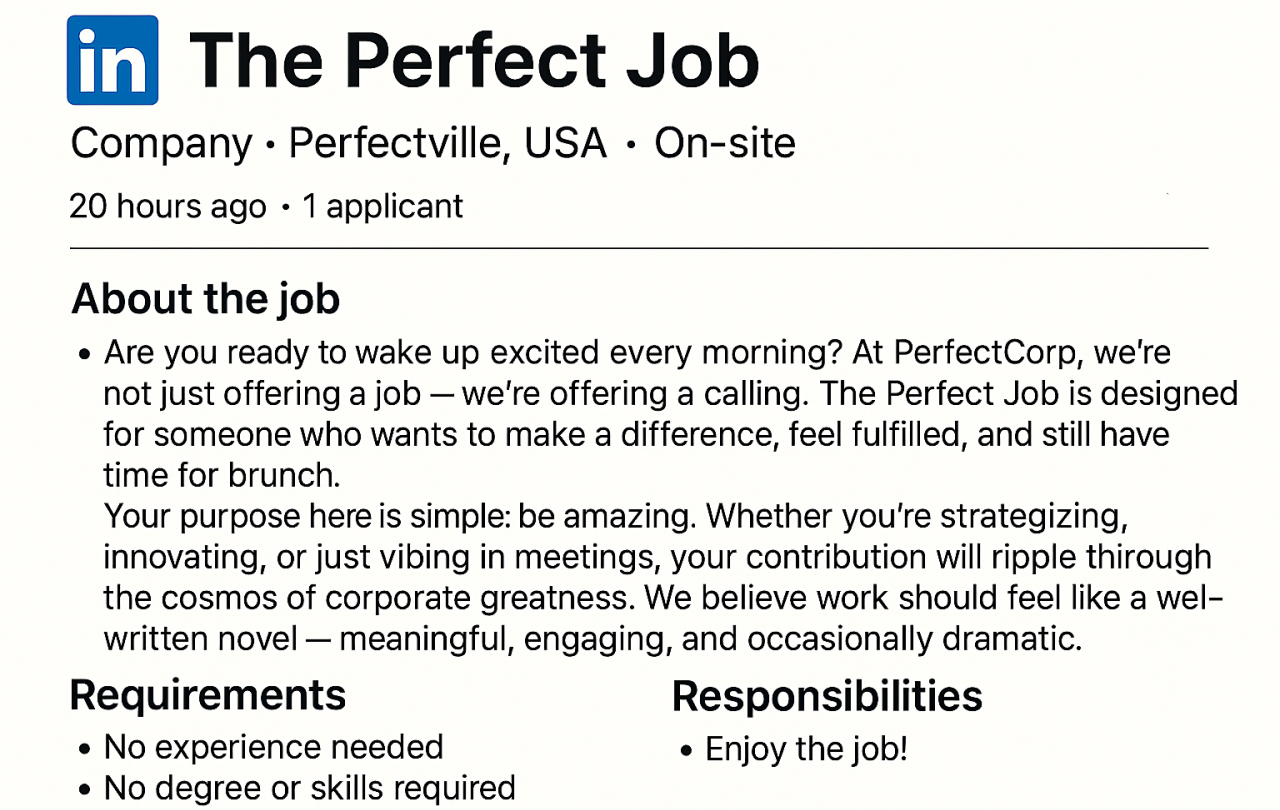

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 was a paradigm of wrongful aggression; if war is ever justified as, I think, an imperfect world forces us to accept, it is in such circumstances. Those who would contest such aggression, in defence of innocent lives and sovereign states, need the weapons to be able to do so, and they need the best weapons that are available. One of the immediate actions that Ben Wallace, then UK Secretary of State for Defence, took in response to the invasion was to surge Britain’s stocks of man-portable anti-tank weapons to Ukraine. One of these, the Javelin weapon, literally gained iconic status, in the meme of ‘St Javelin’, styled as an Orthodox saint. But Javelins do not descend ex nihilo from the clouds: they need to be manufactured by advanced industries.

The defence industry, then, may certainly play a valuable role in a country’s economy. But more than that, in a world of predatory and repressive states, and violent non-state actors, it is a moral necessity. Isaiah foresaw, prophetically, a time when swords will be turned into ploughshares and spears into pruning hooks. But this side of that new reality, we need states that protect the innocent, and without a defence industry to equip the state to do so, the innocent lie vulnerable. If the state is, as St Paul had it, commissioned to punish the wrongdoer, ‘not bearing the sword in vain’, someone must make the swords. The peace dividend at the end of the US-Soviet Cold War has been spent, and we are in ‘the foothills’ of a new one, as the late Henry Kissinger described it. Ploughshares later; it must be swords now.

How long have we got? It is a basic principle of military planning that, while you should structure your own operations around the enemy’s most likely course of action, you should also, and crucially, have contingencies for the enemy’s worst-case course of action. That worst-case may be with us sooner that we think. In the lead-up to the recent Munich Security Conference, the Estonian intelligence chief estimated that Russia is preparing for confrontation with the West ‘within the next decade’; the chair of Germany’s Bundestag defence committee indicated five to eight years; and the Danish defence minister suggested three to five years.

With procurement timelines for advanced equipment—such as main battle tanks, frigates, and next generation fighter aircraft—typically taking over a decade, the urgent priority is for defence investment now. The UK’s Armed Forces are in a parlous state, as the recent cross-party report by the House of Commons Defence Committee makes clear. This investment in defence will not be cheap, and the difficult political task is deciding what spending to cut to allow for this uplift. But this debate cannot wait, and politicians must lead the country now in the required mind-set shift. Poland is the only NATO country to have convincingly demonstrated that it understands the times we live in, by investing seriously in its army. The UK government certainly wills the end, of ensuring the country’s security. The present question is whether it wills the means.

The St Javelin icon meme