Suicide is a tragedy that leaves devastation in its wake for individuals, families and communities - but it remains shrouded in stigma. Whilst those who die by suicide are grieved and mourned amongst their communities, those who experience suicidal thoughts or who survive suicide attempts are often dismissed as ‘attention-seeking’ or ‘dramatic’.

The truth is, our response as a society to suicide is one which often ignores those who are most vulnerable until it is too late. According to the UK Office for National Statistics, the number of people dying by suicide has risen steadily since 2021, and whilst some of this can be attributed to the way in which deaths are recorded, it also represents a real and urgent need to change the narrative around suicide and the suicidal.

As the need has risen, we have also seen that services seeking to support those struggling with rising costs and rising demand.

Just 64 per cent of urgent cases and 72 per cent of routine cases were receiving treatment within the recommended time frames and the proportion of NHS funding being allocated to mental health falling between 2018 and 2023 highlights that the parity of esteem for mental health promised back in 2010 seems to grow further away.

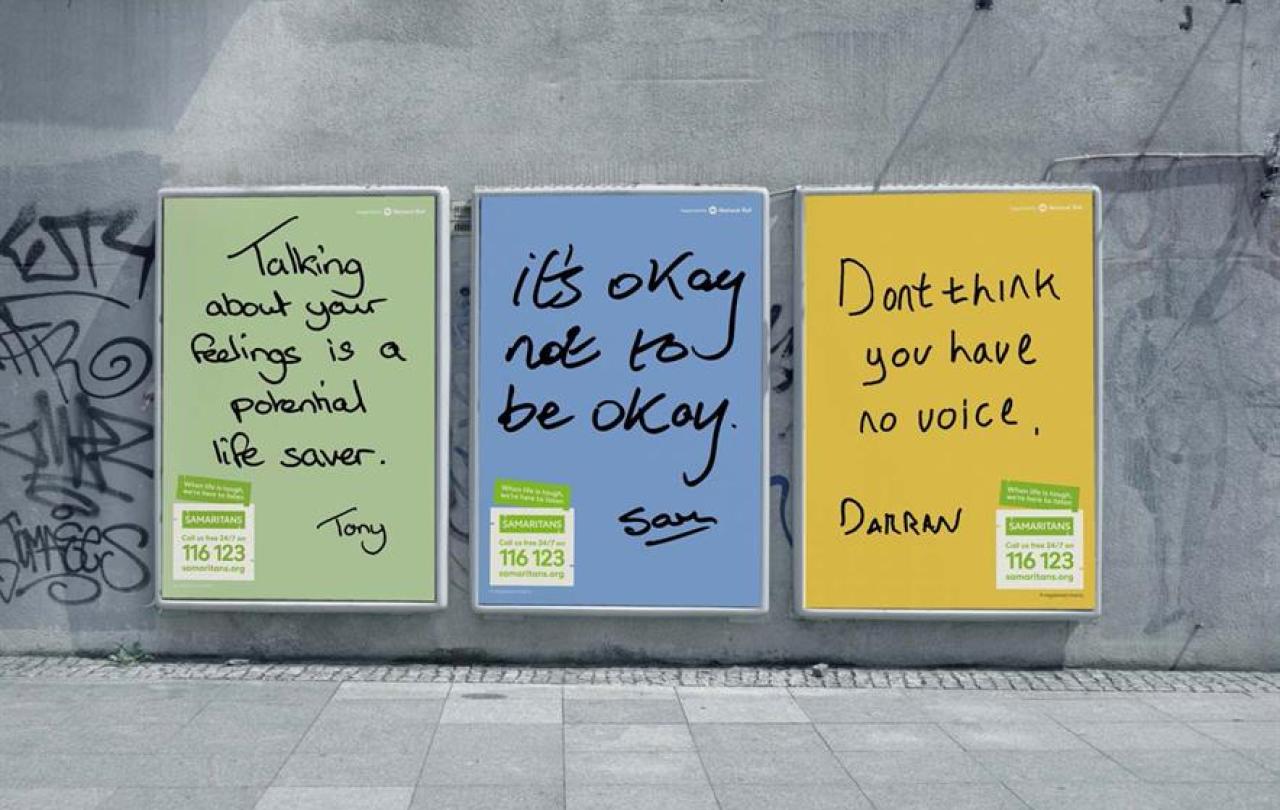

Against this backdrop, for over seventy years, the Samaritans have been synonymous with suicide prevention, working where the health service has struggled to be. It’s sometimes been referred to as the fourth emergency service and has been providing spaces, mainly staffed by volunteers, in person, on the phone and online for people to express their despair in confidence.

And yet earlier this year, it was announced that over the next decade, at least 100 of its branches would be closing, moving to larger regional working and piloting remote call-handling.

Whilst this might be an understandable move considering the economic landscape for the Samaritans, it risks not only a backlash from the volunteers upon which Samaritans relies but also reducing the community support that locally resourced hubs provide.

Suicide prevention cannot be done in isolation; it has to be done in and with community.

Even the most well-trained and seasoned volunteer might find particular calls distressing, and the idea that they would have to face these remotely, without other volunteers to support them, is concerning.

I think this needs to be a wake-up call, not just for the sector - but society as a whole. Because when it comes to suicide, we need to work together to see an end to the stigma and a change in the way people are supported.

Suicide prevention cannot be left up to charities, we all have a role to play.

It matters how we engage with one another, because suicide can affect anyone. There are undoubtedly groups within society who are at a higher risk (for example, young people and men in their middle age).

Still, nobody is immune to hopelessness, and even the smallest acts of kindness and care can help to prevent suicide.

In the Bible story of the Good Samaritan, from which Samaritans take its name, Jesus tell the story of a man brutally robbed and left for dead on the roadside. A priest and a Levite avoid the man and the help he so clearly needs, but a Samaritan (thought of as an enemy to Jesus’ audience) was the one to not only care for his physical wounds, but also pay for him to recuperate at an inn.

We need to have our eyes open to the suffering around us, but also a willingness to help. It probably won’t be by giving someone a lift on a donkey as it is in the story(!) but it will almost certainly involve asking the people we meet how they are and not only waiting for the answer, but following it up to enable people to share.

It might require us to challenge the language used around suicide; moving from the stigmatising “committing suicide” with its roots in the criminalisation of suicide which was present before 1962 to “died by suicide”, and shifting from terms like “failed suicide attempt” to “survived suicide attempt” so that those who must rebuild their lives after an attempt are met with compassion and not condemnation.

Above all, we need to be able to see beyond labels such as “attention seeking” or “treatment resistant” to reach the person whose hope has run dry, and allow our hope to be borrowed by those most in need, both through our language and our actions.

Support Seen & Unseen

Since Spring 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,500 articles. All for free.

This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief