Do you value authenticity? Do you distrust herd-instinct? Do like it when people walk the talk and practice what they preach? Have you, or someone you know, ever faced an existential crisis, rejected cultural religion, or taken a leap of faith?

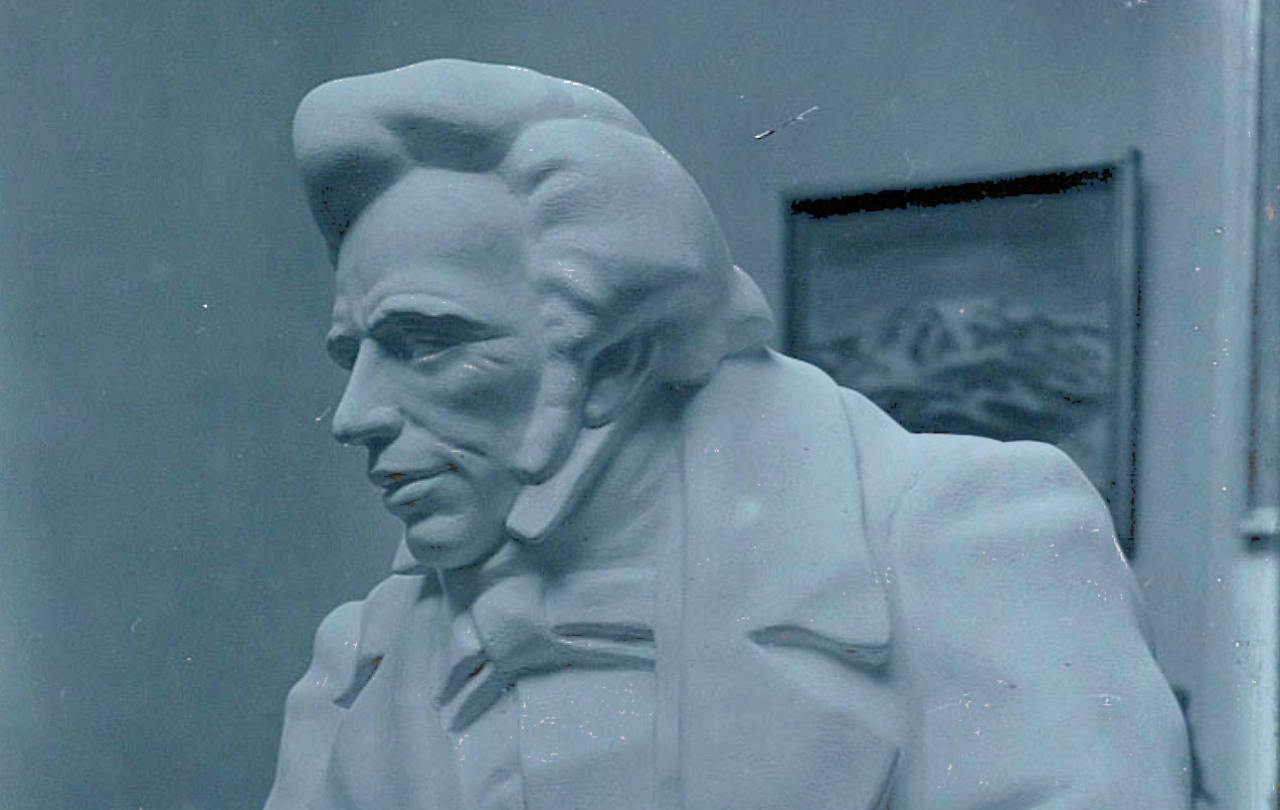

If you can answer yes to any of these questions, then you have been shaped by the words and life of the Danish thinker and rabble-rouser Søren Kierkegaard. He died in 1855, never knowing an audience for his philosophy outside of his native Copenhagen. Yet today, more perhaps than any other, Kierkegaard stands as the philosopher you never knew you knew.

Søren Kierkegaard (SOO-ren KEER-ka-gor) lived during the Danish Golden Age, the most civilised era of Europe’s most civilised country. Danish science, poetry and thought were at their highest, political ideas were thriving and the economy booming. Copenhagen’s chattering classes were at their most confident. It was into this coterie of smug satisfaction that Kierkegaard burst like a bombshell. The result was a man of deep contradictions. A literary genius who poked holes in literary pretensions. A brilliant philosopher who openly mocked philosophy. A religious thinker who wrestled with faith, God and questions of ultimate meaning yet he despised priests and theologians above all else. He is one of history’s most profound Christian thinkers who devoted his entire life to attacking Christendom. The weapons in Kierkegaard’s arsenal of this attack are the gifts he has bequeathed to the modern world.

Authenticity

For Kierkegaard, the main problem with 'Christendom' was the way that all matters of ultimate personal meaning were answered by one’s membership in the group. To put it bluntly: Europeans and Americans assume they are Christian, not because they have made a compelling decision regarding faith, but simply because they are European and American. The result is a boon to nationalism, but a blow to 'authentic existence'. Our modern culture values pliant civilised citizens above all else. People are rewarded for aligning their purpose according to that of their nation, and punished when they deviate from the path, for example, when they make ultimate life choices that put them in a collision course with the values of their home culture. The outcome is that modern life amounts to not much more than herd-instinct. We live in mobs which require personal authenticity to be subsumed into the crowd. As a result, Kierkegaard saw that the modern civilisation Christendom built is largely inauthentic and deeply inhuman.

It is only by rejecting the false identity offered by pliant membership of the herd that one can find one’s authentic self.

The Leap

His solution for all this civilised inauthenticity was 'the leap', often understood as 'the leap of faith'. For Kierkegaard, 'leaping' is what happens when you risk jumping out of your comfort zone for the sake of becoming a real person. The leap is away from meagre safety and out into the unknown. When people make the leap, two things happen: one, they find themselves. And two, they find their enemies. It is only by rejecting the false identity offered by pliant membership of the herd that one can find one’s authentic self. And yet the herd hates being rejected. People who refuse to let their inherited culture and nationality dictate their whole story will soon find that nation and culture do not offer unconditional love. The leap of faith is a leap into the unknown which offers fulfilment, but it is also a leap away from that which falsely offers security.

You have a say in who you are and who you will become.

Existentialism

Kierkegaard is often described as “the father of existentialism”, which is simply another way to describe a philosophy based on the assumption that your existence matters. “You” are more than the country you were born into, the race you are a part of, or the religion you inherited. Your existence matters more, and your authentic identity is grounded in more, than simply being a cog in a faceless system. You have a say in who you are and who you will become. Existentialism then, is a way of living and thinking which attempts to recognise the responsibility you have for your own existence. For Kierkegaard, most human beings elect not to face the existential questions of their own life, content to remain in the warm bath of the herd. But there will always be a minority for whom meaning and truth matter more than the cold comfort of common sense. Kierkegaard was deeply suspicious of the “sense” that we all share “in common.” The wisdom of the crowd might be good for all sorts of things when it comes to daily life, but it is spectacularly bad when it comes to matters of ultimate meaning.

For daring to suggest that the Danish Golden Age might be smoke and mirrors, Kierkegaard was pilloried by the popular press.

Kierkegaard recognised that existential minorities are rare, good, and often deeply unpopular in their lifetimes. His two favourite examples were Socrates and Jesus: public thinkers who loved authenticity and other people above all else, and were killed as a result by the powers that be. It was for this reason that Kierkegaard felt himself on a “collision course” with Danish Christendom, the religious patriotic culture of his day.

Sure enough, when he died in 1855 it was in the midst of public outcry and demonisation by the established church. The attack came from two fronts, but the undercurrent was what today we would recognise as “nationalism”. For daring to suggest that the Danish Golden Age might be smoke and mirrors, Kierkegaard was pilloried by the popular press. Mean-spirited cartoons lampooning his physical appearance were published weekly, and children were encouraged to mock him in the streets. It is said that a whole generation of boys were not called “Søren” because of the association with his name. For their part, the official representatives of Danish Christianity were also appalled at Kierkegaard’s cheek for pointing out that their beloved apparatus of church, state and patriotism bore zero relationship to the way, words and life of Jesus. The culture that Christendom was proud to have built, was, for Kierkegaard, the very thing that was stopping people from discovering their true selves, authentic existence and real love. Behind the sentimental language of the love of nation lurked a hard-hearted herd mentality built on exclusion, hypocrisy and pride.

‘Here was someone who was seriously wrestling with this terror, this suffering and this sorrow. It resonated deeply with me.’

Kierkegaard’s existential protest against religious nationalism was largely unheeded in his lifetime. Yet in 1944, the world war still raging, US President Franklin D Roosevelt called an aid into his office. “Have you ever read Kierkegaard?” asked FDR. “Well, You ought to read him. It will teach you about the Nazis. Kierkegaard explains the Nazis to me as nothing else ever has. I have never been able to make out why people who are obviously human beings could behave like that... Kierkegaard gives you an understanding of what is in man that makes it possible for these Germans to be so evil.”

In 1959, Martin Luther King Jr. was invited to write about his path to peaceful and lasting social change. In Pilgrimage to NonViolence he wrote about discovering the philosophy of Kierkegaard: “Its perception of the anxiety and conflict produced in man’s personal and social life […] is especially meaningful for our time.”

In 1965 a young African-American man, barred from using his main library due to racist nationalism, gets his reading from a different source: “In reading Kierkegaard from the Bookmobile...here was someone who was seriously wrestling with this terror, this suffering and this sorrow. It resonated deeply with me.” Cornel West would go on to study philosophy, eventually becoming a leading public intellectual and activists for racial justice. T

To this list of Kierkegaardians we can also add Ludwig Wittgenstein, TS Eliot, Jean Paul Sartre, Dorothy Sayers, Flannery O’Connor, and Hannah Ardent, to name but a few. Surely the Inkling, author and publisher Charles Williams was correct when he wrote of Kierkegaard in 1939: “His sayings will be so moderated in our minds that they will soon become not his sayings, but ours.” If you value authenticity, if you mistrust the herd instinct of crowds, if you have had an existential crisis, if you or someone you know has ever taken “a leap of faith” then you are living and thinking with words and along lines laid down by Søren Kierkegaard, whether you know it or not.