Small Things Like These is a novella by the Irish writer Claire Keegan. Published in 2021, it compresses a remarkable story into 128 pages. Acclaimed widely by critics and readers, it follows Bill Furlong, a fuel merchant living in the small County Wexford town of New Ross in 1986, as Christmas approaches. While delivering coal to the local convent, Bill makes an alarming discovery. Memories of his childhood begin to press in on him and he finds himself in an existential crisis.

Like her previous (very short) work, Foster, Small Things Like These is an understated book with a searing moral clarity. And just as Foster was adapted for the screen – in the astonishing Irish-language film The Quiet Girl – a movie version of Small Things Like These is now likely showing at a cinema near you.

The movie is built around a stellar performance from Cillian Murphy. It would be criminal if his name is not featured among the shortlists when awards season comes round. Many of the film’s most arresting scenes feature close-ups of his face as Bill wrestles with the implications of his discovery and the phantoms of his past. The effect is that the film serves as an almost literal portrait of what it means to be a decent person.

The story begins with Bill making a delivery to the convent. He sees a mother drop off her screaming daughter to the back door, where she is met and manhandled inside by a nun. The teenager protests passionately, but to no avail. The viewer understands that this girl has “fallen pregnant”, to use the Hiberno-English idiom that was so common in the twentieth century. She has been dispatched by her family to this institution to serve out the months of pregnancy and to remove any shame or taint from their reputation. Bill watches as the girl shouts out for her father, who is entirely absent.

And, after a tense interaction with an aggressive nun, he goes home to his five girls and his wife, clearly shaken.

A few days later, unable to sleep, haunted by memories of his own childhood being raised by a single mother, with an absent father, relying on the kindness of a wealthy local landowner, he begins his deliveries before dawn. As he deposits peat briquettes in the coal shed of the convent, he discovers a teenaged girl abandoned in the corner of the tiny, filthy room. She is in deep distress and Bill responds instinctively, wrapping his coat around her shoulders and bringing her inside to the convent.

While the existence of Magdalene Laundries and Mother and Baby Homes were not a secret in twentieth century Ireland, the exact details of their operations were not widely understood. With these two encounters, so close together, and his own personal biography as the son of a woman who was subject to exactly the same marginalising dynamics, Bill can no longer be satisfied to turn a blind eye to the oppression and alienation endured by those sent for reformation.

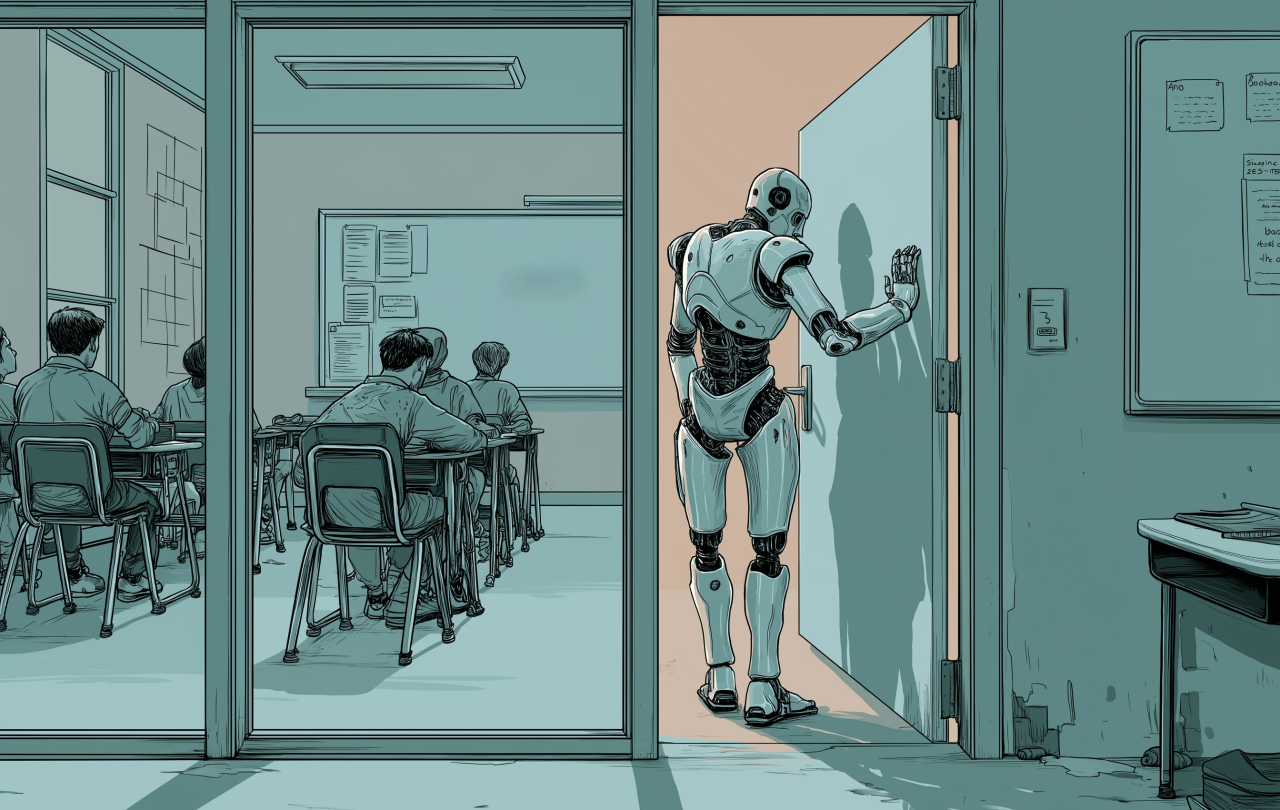

It evokes the ways in which all such systems of oppression are socially constructed and maintained. Otherwise, good people learn to look the other way.

The film gathers momentum as Bill is forced to confront the way his mother had been treated for “falling pregnant” and the reality experienced by girls the same age as his daughters who were in a similar situation. In the midst of his existential angst, he finds little solace in the no-nonsense pragmatism of his wife who reminds him “there are things you have to ignore” to get on in life. He is taken aside by his local publican, a woman who has similarly scrabbled up from humble origins to establish a thriving business and cautioned to not make trouble for the nuns since “their fingers are in every pie in the town”.

I will refrain from fully revealing every detail of the film’s plot. But this element of the screenplay – where Claire Keegan along with Enda Walsh – draw out the sense in which the oppressive ecclesial institutions were enabled and even sanctioned by the wider population is exceptionally well done. The film does not pull any punches on the evils that were committed in the name of churches in Ireland. Indeed, if anything, the presentation of the nuns veers too far towards caricatures of pure malevolence. But with surgical precision, it evokes the ways in which all such systems of oppression are socially constructed and maintained. Otherwise, good people learn to look the other way.

And that is the lasting significance of this film. Toni Morrison has spoken about how it can seem harder to write about goodness than evil. “Evil has a blockbuster audience; goodness lurks backstage.” In Small Things Like This, Claire Keegan introduces us to a hardworking small business owner who treats his staff well, a loving father who seeks to care for his wife, a man who lives down a back street of a provincial town in an overlooked part of a small island on the periphery of Europe. And in this very definitively backstage context, he is presented as heroic in his pursuit of the Good.

We all fancy ourselves to be the one person who would stand up and oppose systems of oppression if we ever found ourselves enmeshed in them. Cillian Murphy’s depiction of Bill Furlong whispers to us that we likely are enmeshed in just that way and are choosing not to notice. Small Things Like These is a heavy film that somehow liberates. It reminds us that there is, within each of us, this appetite for seeing the Good and bring brave enough to do it. It is worth your time far more than any competing blockbuster.