In the course of his coronation on May 6 Charles III will be presented (the technical term is invested) with a number of ancient objects and clothed in various special garments. Known collectively as the coronation regalia, all have deep symbolic significance and point to the Christian basis of the ceremony and of the British monarchy.

Crowning glory

The crown which will be placed on the king’s head by the Archbishop of Canterbury is, of course, the most splendid and iconic symbol of majesty. Like the other items of the coronation regalia, it was specially made for the coronation of Charles II in 1661 to replace the medieval regalia which had been broken up and melted down during the time of the Commonwealth and Protectorate when England was without a monarchy in the mid-seventeenth century. Known as St Edward’s Crown, it replaced a medieval original which is said to have been made for King Edward the Confessor, a saintly eleventh century king who built the original Westminster Abbey and was officially canonised as a saint in 1161. Weighing nearly 5 lbs and made of solid gold, its rim is set with precious gems and from it spring two arches symbolising sovereignty. Where they meet there is a gold orb surmounted by a jewelled cross, a reminder of the cross of Christ and of His sovereignty over all.

Placing St Edward’s Crown on the monarch’s head, the Archbishop traditionally says:

‘God crown you with a crown of glory and righteousness, that having a right faith and manifold fruit of good works, you may obtain the crown of an everlasting kingdom by the gift of him whose kingdom endureth for ever.’

The orb’s different empire

The crown is not the only conspicuous symbol of Christ’s power and sovereignty that will make an appearance at the coronation. The orb, which is customarily put into the monarch’s right hand before his crowning, is the oldest emblem of Christian sovereignty, used by later Roman Emperors and Anglo-Saxon kings. A ball of gold surmounted by a large cross thickly studded with diamonds and set in an amethyst base, it acts as a reminder, in the Archbishop’s words, ‘that the whole world is subject to the Power and Empire of Christ’. Its first appearances in Britain are on a seal of Edward the Confessor in use between 1053 and 1065 and in a depiction of the crowning of King Harold in the Bayeux Tapestry. It is significant that the complex planning of Charles III’s coronation is code-named ‘Operation Golden Orb’.

The wedding ring

The ring, in Latin annulus, which is next traditionally placed on the fourth finger of the right hand has often been specifically made to fit the new sovereign, although Elizabeth II used an existing one inlaid with a ruby and engraved with St George's cross. It is presented to symbolise the marriage of monarch and country and was known in medieval times as ‘the wedding ring of England’.

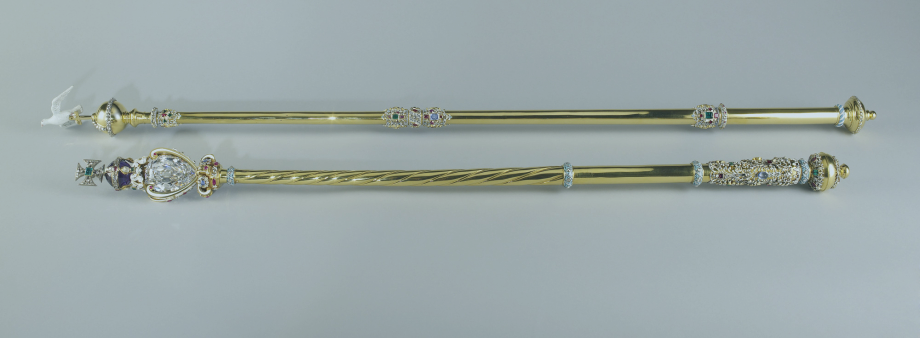

The sceptre’s power

The final pieces of regalia with which a monarch is traditionally invested before being crowned are the rod and sceptre, known in Latin as the baculus and the sceptrus. These may originally have derived from the rod and staff mentioned in Psalm 23. The solid gold sceptre has since 1910 contained the largest clear-cut diamond in the world, part of the massive Cullinan diamond found in the Transvaal in 1905. It is surmounted by a cross, which stands for kingly power and justice. The longer rod, also made of solid gold, is surmounted by a dove, signifying equity and mercy.

Working clothes

There is also deep spiritual symbolism in the traditional coronation garments worn by the sovereign. Based on ecclesiastical vestments, they are designed to emphasize the priestly and episcopal character of monarchy and are put on immediately after the anointing which is carried out with the king or queen wearing a simple linen shirt to symbolise humility. The colobium sindonis, a sleeveless garment made of white linen with a lace border is to all intents and purposes a priest’s alb or surplice. Over it is put the supertunica, a close-fitting long coat fashioned in rich cloth of gold, identical to a priest’s dalmatic - a long, wide-sleeved tunic. A girdle of the same material put round the waist has a gold buckle and hangers on which to suspend the sword with which the monarch is girded. A cloth of gold stole is placed over the shoulders. At a later stage the sovereign is traditionally vested in the imperial mantle, or pallium regale, a richly embroidered cope similar to those worn by bishops.

These garments emphasize that, like priests and bishops at their ordinations and consecrations, monarchs are set apart and consecrated to the service of God in their coronations which are first and foremost religious services. This aspect is further emphasized by the framing of the coronation service in the context of a service of Holy Communion according to the order laid down in the Book of Common Prayer.

The unseen

Some will dismiss the ancient regalia with which the monarch is invested, which have also traditionally included golden spurs, bracelets and swords, as anachronistic medieval mumbo jumbo out of keeping with our modern world. Yet they symbolise in powerful visual terms the sacramental nature of our Christian monarchy which points beyond itself to the majesty and mystery of God. In the words of a former Archbishop, Cosmo Gordon Lang, writing just before he presided at the coronation of King George VI, these ancient rites and ceremonies demonstrate ‘that the ultimate source and sanction of all true civil rule and obedience is the Will and Purpose of God, that behind the things that are seen and temporal are the things that are unseen and eternal.’