Stories define us. Especially genesis stories, stories of formation, of how things began. Because beginnings often harbour within them all the seeds of future growth, defining so much of what’s to come, size, shape, colour, character even, and, what’s true of the natural world, is also, so often, true for our own life journeys.

As I embark upon a particular journey, in many ways the centrepiece of my three-month sabbatical break from my life in Christian ministry, I find myself reflecting on a bigger, longer, greater journey that has, consciously and unconsciously, shaped a good deal of that whole life.

I’m writing these words on a train, from Boston, Massachusetts to Washington DC, eight hours through a variety of weather, landscapes, and a whole variety of provincial, and city stations, some of them famous, others vaguely familiar, still more completely unknown. I’m off in search of flesh on the bones of a story, a much-fabled tale, of a man and his life.

I came across a book, a thin tome and looking pretty sorry for itself, clearly already well thumbed. I started to read it and quickly became transfixed.

But first, more of mine. I grew up, the youngest of four children, in a pretty traditional working-class family in Bristol that, by virtue, of my parents owning their own home and my two older brothers having gone to university at the end of the 60’s, now found itself, contrasted starkly with all of my Aunties and Uncles, knocking on the door of middle-class comfort.

By the early 80’s however, as I was preparing to leave school, that all looked, and felt, a little different. Not having acquired sufficient spiritual credits to attend the city’s church school, and with my brother’s academies having long since migrated to the private sector, I’d meandered my way through the local comprehensive, with enough wisdom to avoid most of the outcomes for which it was renowned, but not enough application to really supersede them all. What I did learn though, was a strong sense of justice, together with a certain perplexity as to why this wasn’t more universally shared and even, in some cases its absence appearing to be celebrated.

In our playing fields and its environs there was a pretty regular flow of what today would be called ‘racially aggravated incidents’. I vividly recall one boy in my year having his legs nastily broken. What I also remember though, was the daily ritual of being handed a National Front promotional leaflet at the school gate. Difference begetting antagonism, spawning violence and demanding retribution, seemed to be the story, I hated it, and instinctively railed against it.

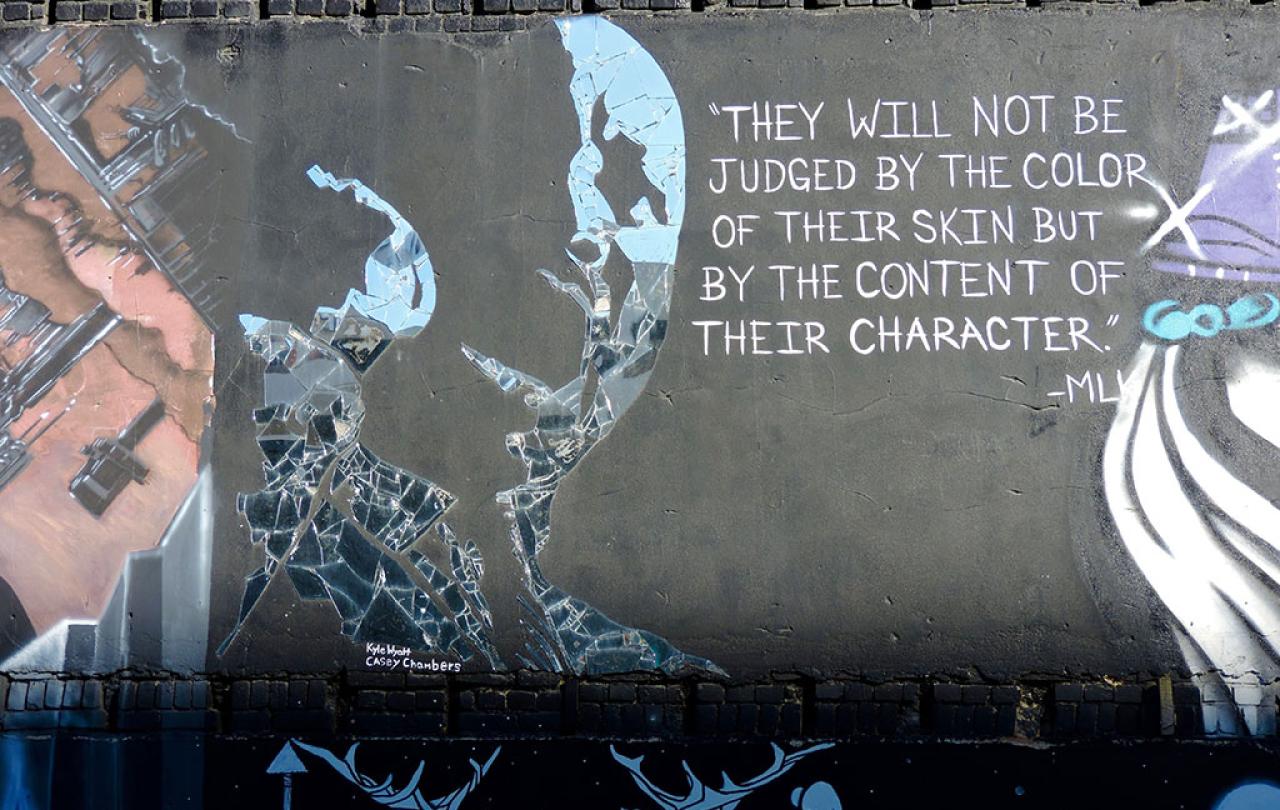

My response was hardly dynamic or revolutionary. I think I went on a march or two, I remember buying a mug once, yes, I was that sort of kid, oh, and I put a poster on my wall. Again, a fairly generic image, probably bought from Athena, of a man, half a generation older than me and a whole world away. A man, on a platform, speaking, and some of the words he spoke, super-imposed over the top of him, ‘I have a dream …’

A short while later, at a friend’s house, I came across a book, a thin tome and looking pretty sorry for itself, clearly already well thumbed. I started to read it and quickly became transfixed, it was more speeches from this same man, yet these were different, they spoke more about motivation than outcomes, about the passionate ‘Why’ of action, more than the ‘How’ of achieving meaningful change. It was ‘Strength to Love’, a book or sermons for, I discovered this man was not a politician but a preacher.

To cut a long story short, this encounter, these thoughts, along with a few others, caused me to translate my hitherto rather semi-detached relationship with my local Baptist Church into something more committed. Within eight years I was in London, training for ministry, and I‘ve now been in Church leadership for 30 years.

For stories, rooted in truth, throw a spotlight on those lived, core beliefs, out of which glorious, effective, fulfilled lives develop.

And so, our stories intertwine, mine and Martin Luther King’s, oddly, unexpectedly, yet profoundly, and so I find myself on a train, to DC, and then on to Atlanta, Montgomery, Birmingham, to dig more into his story, to discover more of my own.

Because stories not only define us, they fuel us. Idealism is all well and good, but where does it come from, and how might it be sustained? Inspiration, is often illusive, a fiery necessity for a purposeful effective life, in any sphere, but it needs a source, something in which to be rooted. A craving for justice, an attraction towards generous love, a passion for human fulfilment, and a whole host of other things, all seem like good and obvious things, in and of themselves, but why? And, given they are frequently costly and hard fought, from where might the motivation come to make the necessary sacrifices? Martin Luther King did what he did because he believed what he believed, given that, it seemed obvious, inevitable, for him to act, whatever the cost. The Apostle Paul encouraged the first generation of Christian believers, living challenging lives at the heart of the empire, in Rome, to tell stories; ‘How can they hear unless someone tells them?’ he reasoned, and then, with a flourish, ‘How beautiful are the feet of those who bring good news!’

It seems we need preachers, storytellers, more than we do politicians. For stories, rooted in truth, throw a spotlight on those lived, core beliefs, out of which glorious, effective, fulfilled lives develop. With that knowledge in mind, I’m off on my journey, to experience tales, old and new, and see what they do to me, I’ll let you know what I discover.