When I presented the book I Love Russia by Elena Kostyuchenko for purchase at the counter, my only thought was for what the bookseller would think. Was I a Putin sympathiser and apologist for the war in Ukraine? It says a lot about how we have unconsciously embraced Putin’s world as the only take on Russia. There is an indigenous saying that Russia is not Moscow and Moscow is not Russia. By the same token, Putin is not Russia, however much he would like us to think this; it is naïve and prejudiced of us to allow the largest country in the world to be defined by its dictator.

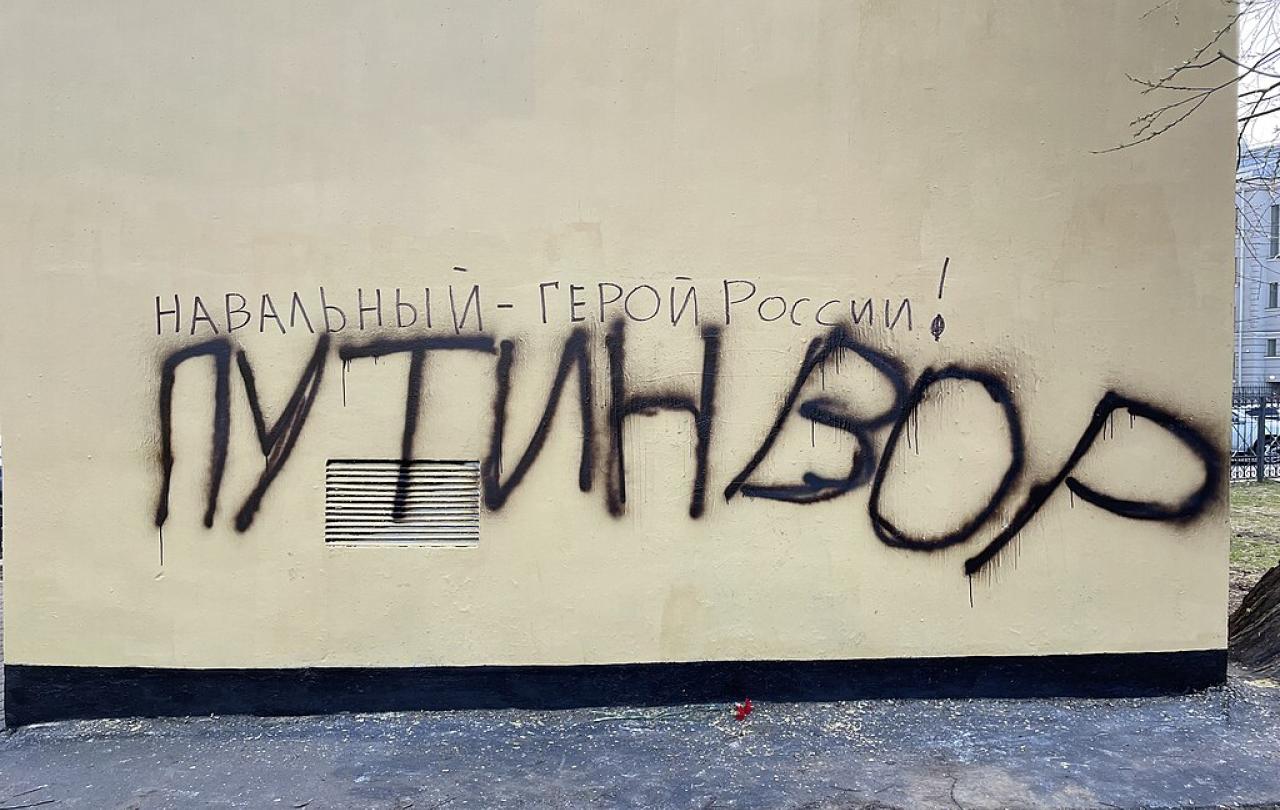

Elena Kostyuchenko, and Alexei Navalny in his posthumously published book Patriot, belong in different generations to Putin and inhabit another moral universe. Navalny has done more than anyone to call out the epic levels of corruption and dark cynicism of the Putin era. This is a Mafia state, as Luke Harding observes. Navalny believes there are twenty people who rule in Russia, with staggering levels of visible and hidden wealth, and a further one thousand who eat from their trough. The rest of the country includes those who are duped by state media, those who don’t want to know or keep their heads down or don’t care, and those who testify to the truth.

This latter cohort shows remarkable courage, because they are being silenced, one by one, through prison or murder. Navalny died in prison after previously being poisoned in Siberia; Kostyuchenko was poisoned while in Germany and has been targeted for assassination elsewhere. Before them lies a sobering roll call of journalists and politicians like Anna Politkovskaya, Boris Nemtsov and Igor Domnikov whose murders are clearly attributable to what they have said about the crimes of Putin and his associates.

Elena Kostyuchenko’s journalism takes her to Russia’s abandoned people and places. Derelict and decaying hospitals where the young, the addicted and the dispossessed gather; the mothers of Beslan who are beaten up and persecuted because they want the truth about that fateful siege; psychiatric hospitals with no resources or patient care; landscapes depleted by corrupt extractive industries. She is inspired by the fearless reportage of Politkovskaya and her writing bears the imprint of Svetlana Alexievich, with its gift for listening and attention to the wonderful ordinariness of human life. Her walk down the dark parade of Russia’s casualties is a tribute to the finest traditions of journalism, which carry the echo of the voice of Christ in their attention to those who lose out in this world.

In prison, Alexei Navalny learned the Sermon on the Mount by heart; his conversion from the routine atheism of his Soviet upbringing being triggered by the birth of his and Yulia’s first child, Dasha. He is wry, sardonic, stubborn, implacable – displaying an other-worldly willpower. It is hard to compute the courage it took to return to Russia after being poisoned with Novichok, knowing it would surely lead to imprisonment, mistreatment and death:

One day I made the decision not to be afraid. I weighed everything up, understood where I stand – and let it go.

Of the pain inflicted on him in prison for speaking the truth about Putin’s Russia, he says:

I have decided that this is my own pared-down version of suffering for the faith, a moment of suffering for being a believer. Happily it does not entail being dismembered, stoned to death, or having the lions set on me.

And yet the totality of his life was not far short of this. He skates over much of the abuse, but references being woken every hour of every night for a personal roll call. When other prisoners were primed to shout at Navalny for long periods from close range, it is deeply moving to visualise him shouting back and not backing down. Over time, his bespoke prison regime became steadily more abusive and isolating, directed in his view from the Kremlin.

There is absurdity at the heart of the system and he confronts those responsible for it, rather than meekly submitting to it. In the late Soviet era, criminal law was so comprehensively drafted that anyone could be picked up for an infringement if this was politically expedient. In Putin’s Russia, we have returned to the Stalinist period where offences are simply made up in a dark Wonderland. It is rule by law, not of law.

The editor of Novaya Gazeta, Dmitry Muratov, uses a particular metaphor. He says that Putin and his Kremlin officials act like priests who mediate a believer’s relationship with God. They have become intermediaries for how Russians are supposed to experience their country, telling them what to think and feel about it. If so, then Russia is ready for a new reformation, where people claim their own organic relationship with a nation that means so much to them. There are already enough martyrs for this new reformation while Putin continues to speak power to truth. Those of us who care about its people and its future do not need Putin’s malign priesthood to interpret Russian life. There is a different Russia, waiting to be discovered.

Join with us - Behind the Seen

Seen & Unseen is free for everyone and is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you’re enjoying Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Alongside other benefits (book discounts etc.), you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing what I’m reading and my reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief