In 2016, five-year Brooke Blair became an internet sensation after a video of her berating Prime Minister Theresa May went viral. As she put it, she was ‘very angry’:

“Yesterday night, I was out on the streets, and saw a hundred and a million of homeless people. I saw one with floppy ears, I saw loads. You should be out there, Theresa May. You should be, biscuits! Hot chocolate, sandwiches, you should be building houses. Look, I'm only five-years-old. There's nothing I can do about it. I'm saving up money but there'll never be enough. You've got the pot of money, spend some and help people.”

The video struck a chord because a young girl was passionately expressing the distress, anger, sympathy and bewilderment that so many feel when seeing people sleep rough in such a wealthy country.

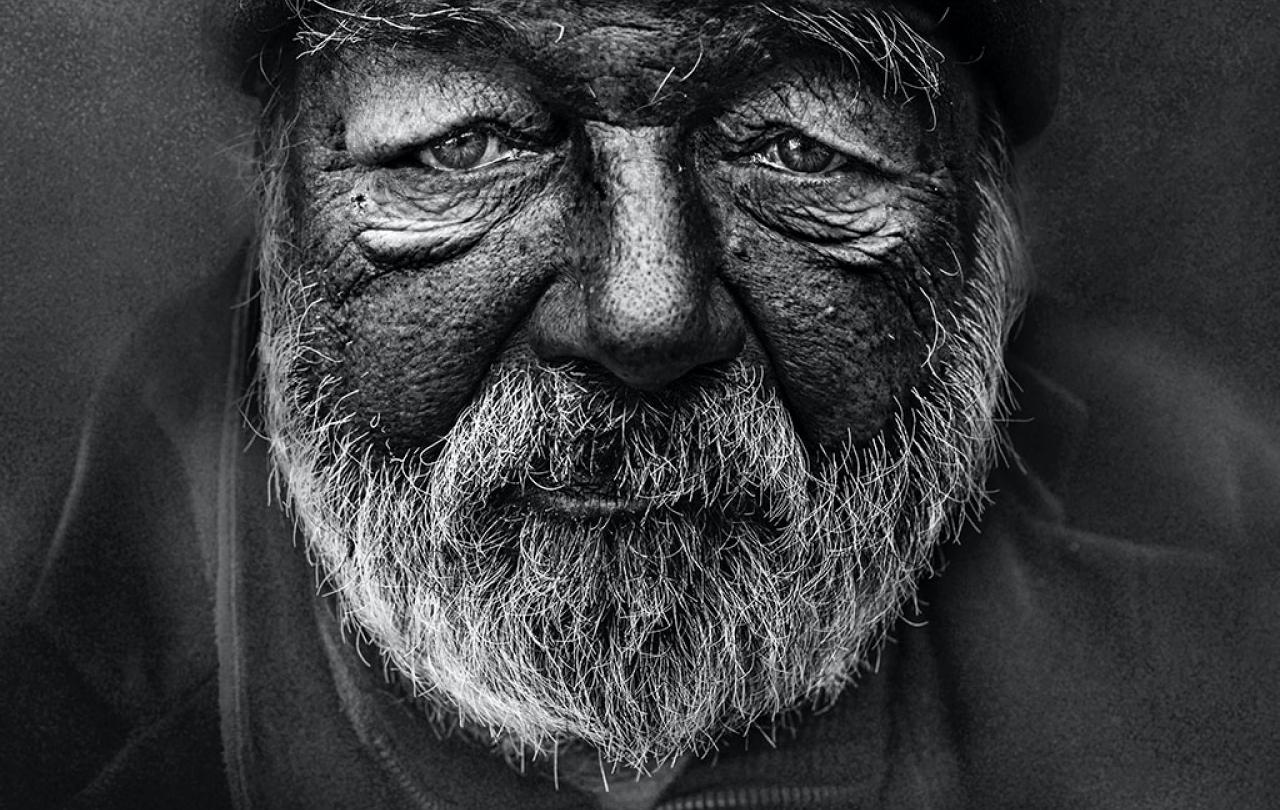

The image of a rough sleeper is an icon of poverty. And just as religious icons represent the sacred, so does each person sleeping rough.

Each rough sleeper is a raw illustration of injustice and social breakdown. The structural issues of poverty and inequality crystalize in the plight of a vulnerable person huddling in a doorway. In them we see an amalgam of both political failure and personal tragedy.

It's personal because we know that each person has a different story about what led them onto the streets. We will always be moved far more by a person than any statistic.

The image of a rough sleeper is an icon of poverty. And just as religious icons represent the sacred, so does each person sleeping rough. A precious human of infinite worth, imprinted with the divine, living in destitution. And just as restoring fragile religious icons is a specialist job, so the task of restoring those who have been homeless is often complex and intricate work.

Today, 10 October, is both World Homeless Day and World Mental Health Day. The two are closely intertwined. It’s a good day to reflect on the nature of homelessness and what we can do in the work of restoration.

We cannot simply remove the tip of the iceberg without addressing the deeper issues ... The water is getting colder and the iceberg is growing.

Rough sleeping is just the tip of a far bigger homelessness iceberg. It receives the most attention because it’s visible and visceral. But it is just a small fraction of the total number of people who have no settled home who exist underneath the waterline: those sleeping in temporary shelters, hostels and squats, sofa-surfing or placed in B&Bs.

It’s the visibility of rough sleeping that gives it political capital. Whilst in power, Margaret Thatcher, Tony Blair, Theresa May and Boris Johnson all launched high profile initiatives with ambitious targets to reduce or end rough sleeping.

In 2018, I was seconded from the Christian charity I was working for into the Civil Service as a specialist adviser on rough sleeping. In the four years I spent in this role I worked under four different Prime Ministers and six different homelessness ministers. Despite some significant progress made before and during the pandemic, the numbers of people sleeping rough and those in temporary accommodation are starting to rise again.

We cannot simply remove the tip of the iceberg without addressing the deeper issues of poverty that it is connected to. The reality is that we have a deep housing crisis in this country. The water is getting colder and the iceberg is growing.

But the challenge is that rough sleeping and homelessness are genuinely complex problems. Politics and economics provide some of the answers but not all. After thirty years of working with people who are homeless, these are the key issues which lie behind homelessness.

Poverty of resources

The most obvious cause of homelessness is the lack of affordable housing. Housing is a resource which is not distributed fairly, and this inequity creates intense pressure and vulnerability. All of this is compounded by austerity, funding cuts and benefit sanctions which have withdrawn support services for vulnerable groups.

As London has become an international playground for the uber rich, many new housing developments are simply investment opportunities. Often people sleep rough outside accommodation no one lives in. It is a stark picture of the failure of the housing market.

This aspect of homelessness is the one that government can do most about. Brooke Blair was fundamentally right – Prime Ministers need to build more houses for those who need them.

A poverty of relationships

But homelessness is more than house-lessness. Homes are more than bricks and mortar: they are places of relationships.

And if you talk with anyone sleeping rough, you are likely to hear of relationships that have gone wrong with partners or with their wider family. Some are fleeing abuse or domestic violence; some have been perpetrators. Relational problems are often a key source of regret and shame; where people carry their deepest scars.

In our concern for people’s rights to the resources they deserve, we should not lose sight of where humans find true meaning and fulfilment. We all have a deep need to know and be known, to love and to be loved. We cannot get away from the importance of relationships and a sense of belonging.

A poverty of identity

Finally, and most deeply, is the issue of people’s inner identity. The essential relationship that everyone has with themselves.

The rise in mental health problems are symptoms of a vulnerability of our inner well-being. For people affected by homelessness, their experiences of exclusion and trauma are both a root cause and an on-going reason for their mental fragility.

And the addictions to alcohol or drugs which are common to many rough sleepers are deeply connected to these psychological vulnerabilities. Drugs become a form of self-medication to ameliorate pain. And however negative, the lifestyle required to maintain addictions can be relatively exciting and can provide each give a day a clear goal. It can be hard to leave such an identity and embark on a demanding journey of recovery.

Homelessness doesn’t just end in a flat. It truly ends in community and connection.

So, in short, homelessness is far more than house-lessness. Houses are a key resource but homes are primarily places of relationships and identity. And the restoration of these cannot be just done by the government. It requires a whole community.

Thirteen years ago, a Christian couple in Peterborough, Ed and Rachel Walker chose to invest their own inheritance into a house for people who were homeless. The idea inspired others: it was simple and innovative: encourage people with wealth to invest in homes for those who are poor. And each home was attached to a local church which provides friendship and support and a critical sense of community.

This is the roots of Hope into Action where I now work. We are now a national charity with 106 homes across the country and last year we housed over 400 people. Our model is a holistic response to the types of poverty I have described.

Our tenants are provided with the resource of a great house where they feel safe and secure. And this is combined with relationships with housemates and the support of local church volunteers. And our whole focus is to empower our tenants to find a more positive identity: whether through purposeful work, on-going recovery or through exploring faith. Last year, fifty percent of our tenants chose to engage in church activities and six took the step to be baptised.

Homelessness doesn’t just end in a flat. It truly ends in community and connection. In our work we see justice and generosity in how resources are shared, compassion in the relationships that are formed, and hope on which people can rebuild a positive identity. Just as a lone rough sleeper is an icon of poverty, each of our tenants is a symbol of hope.