I’m standing next to my bicycle at a petrol station in Blackpool, it is 1am. I’m eating a cheap cheese sandwich and drinking cold coffee from a can. What I want is hot coffee, but the machine only takes cash, and the cash machine charges for withdrawals. I’m making do with cheap and cold, because the need for calories outweighs the need for taste. On this night, I’m cycling from Slaithwaite to Blackpool and back, checking the route for a cycling event I’m organising. It’s an audax: a type of sporting experience typically documented by forecourt-chic social media posts. Its name is derived from the French for audacious.

A glance though long-distance cycling blogs, vlogs and curated media, hints at an experience of transcendence; the emptying of self, in the search of meaning from the zip of tyres over tarmac as the kilometres click past.

The reality, however, can be more mundane: long distance cycling often involves sitting on a weed strewn curb, while a friend fixes a puncture and though the clouds are not quite heavy enough to rain, there’s a mizziness to the air that seeps through your sportwool baselayer. There is no film crew to capture this epic moment, and you’re alone with your thoughts, which are mainly thankfulness that it isn’t your puncture.

I’m a vicar in West Yorkshire, but haven’t always been a vicar, or even a Christian and I’ve been riding bikes for much longer than I’ve been a person of faith. As a child cycling was about belonging, I was part of a BMX community whose hierarchy was measured by how high you could bunny-hop. Later, that belonging was replaced with a different sort of identity, found through music. It was only when I was older and fatter that I rediscovered cycling thanks to my wife, who thought we both needed some exercise.

We loved to explore, and perhaps this physical exploration was why we also began a journey of spiritual exploration.

Together we remembered how to cycle, and as we gathered experiences, we grew in the wisdom of the cyclo-tourist. We learned that mudguards and rain capes are things of comfort and therefore beauty. We loved to explore, and perhaps this physical exploration was why we also began a journey of spiritual exploration. I’ve no intention to suggest that cycling is a gateway drug to Christianity, more that perhaps our curiosity was being fed physically, mentally, and spiritually, in ways that were not of our making.

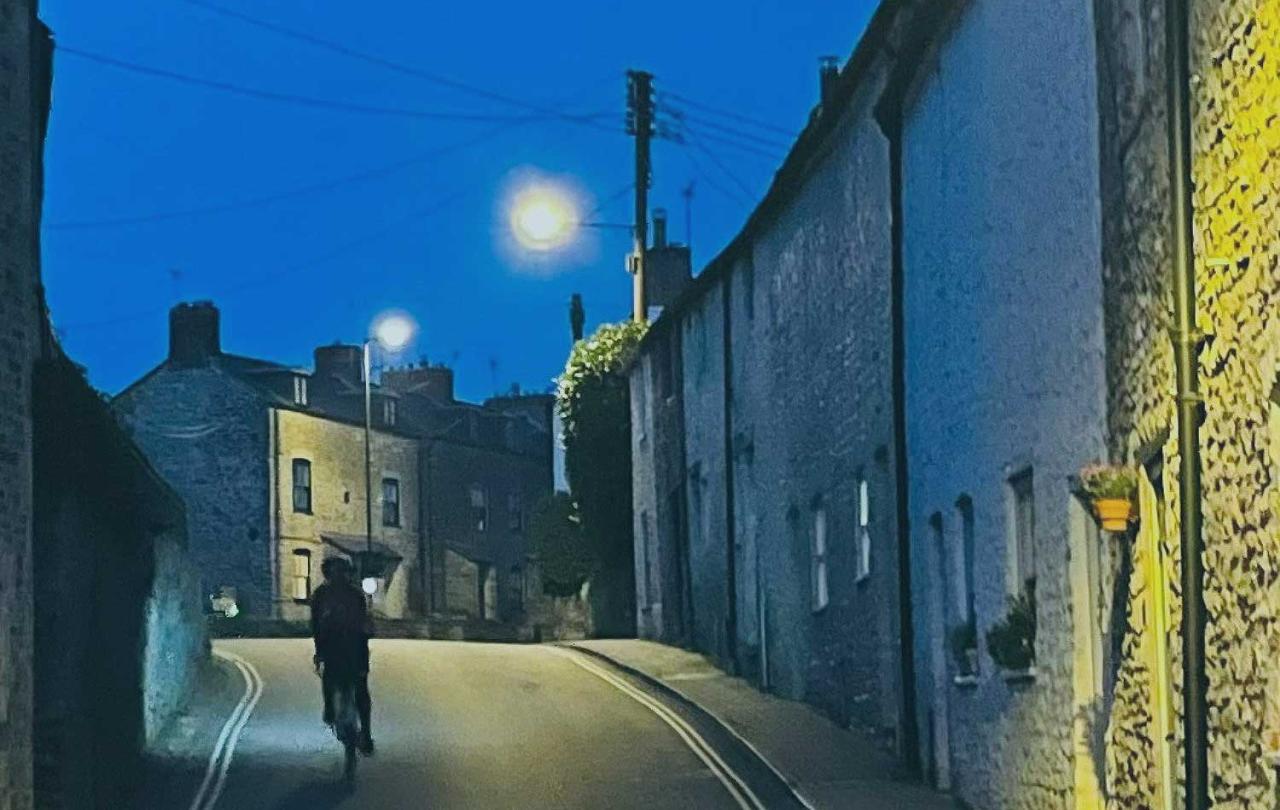

The first time I noticed a spiritual element to my cycling was coming back from a meeting, crossing the North Yorkshire Moors at night. It was autumn and the evening turned to dark quite early, leaving only a puddle of weak bike light to ride with. A phrase from morning prayer returned to me: ‘even the darkness is not dark to you’. A single line from a psalm in the Bible. This one line, on this one night, redefined my relationship with God. Even though all around me had turned to darkness, there was nowhere I could be lost from God.

These remote fans and supporters are constructing narratives to explain rider’s movement, or lack of it. Yet the rules of self-sufficiency mean you are alone, no one can set you back on the right path.

Not being lost is an important element to cycling a long distance, especially in a race. In events like the TransContinental – a multi-day self-sufficient cycle race across Europe, spending hours cycling in the wrong direction could be a racing disaster. Race winner Emily Chappell, in Where there’s a Will, eloquently documents the racer’s experience of being ‘watched over’. She tells of ‘dot-watchers’ following a rider’s GPS tracks across a map of Europe. These are remote fans and supporters constructing narratives to explain rider’s movement, or lack of it. Yet the rules of self-sufficiency mean you are alone, no one can set you back on the right path.

Being alone with your thoughts is a common theme to long distance cycling. While our bodies silently convert glucose into energy through glycolysis, and our muscle memory converts this into kilometres covered, our minds are set free to process our past and present experiences.

During my time at theological college, I wanted to explore the idea of physical exercise being an expression of prayer. I tried to grapple with the wordless way our bodies do what bodies were created to do. Can our bodies worship without words? Is there a physical language of lactic acid, originally written by a creator who celebrates when creation is true to itself? There’s a poetic language in the Bible that hints at this, that

‘the mountains and hills will burst into song before you, and all the trees of the field will clap their hands’.

Pro-cyclist Jens Voigt famously told his legs to shut up… maybe he should have let them sing.

Audaxing, long distance cycling, racing across continents; these are extraordinary journeys in which we might travel from light to darkness and back again. Simultaneously, there is a physical descent from adventurous confidence to uncertain determination, where the will to go on is no longer found in the legs, but in a dogmatic determination to see this through. Then, with the dawning of the day, there is a fresh hope: a hope of warmth and a return to strength. With the dawning of the day, the opening of the first coffee shop and this long-distance cyclist’s prayer is answered.

“O Lord, open my lips,

and I shall drink this coffee.”