“Time’s going really slowly today!”

“Golly – where’s that week gone?”

“It felt like time stood still for a moment…”

“Sorry, I lost track of the time.”

These expressions are common enough to be cliché. I’ve used each of them in the last few weeks. But do they actually make any sense? We all know that time is in seconds, minutes, days, weeks… very reliable, very constant, very scientific. We all know that time doesn’t stand still – how can it?! We know that, don’t we?

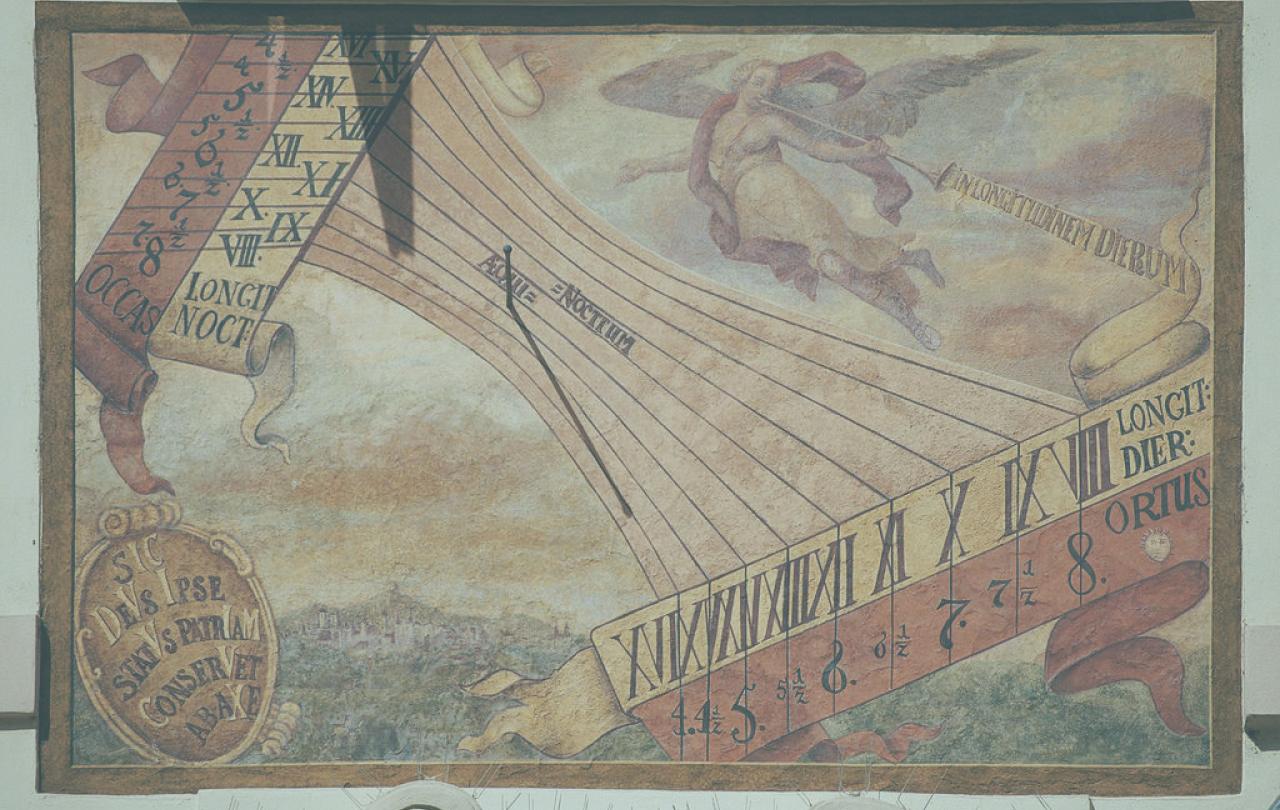

But us modern, scientific cultures can often forget how recent these regimental patterns are. Of course, people and cultures have been measuring time for millennia – Ancient Egyptian sundials, early Medieval monks needing to fit in seven services a day. But time, even in those examples, always said more than just ‘keeping time’… a sundial was especially meaningful in a world where it usually shone every day, and was itself held up as a God; for life in a monastery, worship was the time-keeping device, worship was the rhythm of life.

Time, and particularly our experience of it, doesn’t easily track onto our clocks. We are constantly experiencing time quickly, slowly, forgetfully, meaningfully. Could there be another account of time, not one governed by the Greenwich Meridian, which is – somehow – more real?

The Ancient people of Israel were some of the first to realise that there is more to life than clock-watching. It’s hard for us to imagine how revolutionary the idea of a Sabbath is. But when it became the norm for the Jews to observe the Sabbath every seventh day – to keep it holy – this wasn’t just about being religious. This was about justice and the avoidance of exploitation. In a world where slaves and workers in the field were expected to work every single day, the idea that there should be rest and restoration said something distinctive both about the nature of work, and about the nature of what it is to be human. And it also said something distinctive about hope.

For Christians, hope and the Sabbath are forever now held together in the story of Jesus’ resurrection – the very first Easter day. There’s much that could be said about this. But for our little topic of time, it’s quite explosive. The people of Israel had believed (we think) that death would be defeated by the return of God to his people at the end of time. But here was God – in the flesh – defeating death… and time is still marching on! What are we to make of this?

Something of the end has come in the middle. Time is now warped.

Well, one of many things is that, when Christians confess their belief that ‘on the third day Jesus Christ rose again from the dead’, they are saying that something of God’s ultimate future, his promise one day to be with us forever, what the Sabbath had always pointed towards like a signpost, had now happened once and for all. Something of the end has come in the middle. Time is now warped.

One of the first signs of this ‘warping’, was another day off. The early Christians by and large slotted into the ongoing Jewish observance of Sabbath. But then – treating it as the start of their week – they observed a second day off, a day of feasting and celebrating, and marching through the towns waving banners. The Lord’s day. Resurrection day. Day one – starting all over again, starting afresh, making something new out of the old.

A second sign was this. Time held a new power – a new potency if you like. It wasn’t that the days had somehow changed duration, or our lifespans were altered. No – Christians think that there is a new expectancy in the air. They are to live, Paul writes, as if the fixtures which hold them to this world now no longer hold the same power. ‘Time is contracted’ he goes on (not ‘shortened’ as it’s sometimes translated) – ready to pounce like a cat.

The third sign follows from the second. The Christian experience of time is constantly pulling backwards and forwards. In celebrations and worship, Christians look back and recite God’s mighty deeds from the past. In reciting them in the present, they re-present them. But the point of ‘re-presenting’ these mighty acts was not just to bring comfort to the present; it also reinvigorated hope for the future. Christians – as the Creed goes on – ‘look for his coming again’. The experience of time for a Christian (or, even, a philosophy of history) is not governed by a flat-line Hegelian aufhebung – that every day, every hour succeeds its predecessor. Instead, the past and the future works on the present in a constant swell of recall and expectation.

Christians see their lives held by God’s time. They’re not a clock-watching, ‘progress-reliant’ people. In the resurrection, Christians believe that God has changed the way we view time once and for all. On that, all their hope is founded.

That’s real time.