They say Putin is not in touch with reality. But when it comes to raw fundamental political reality, maybe he is? It could well be true that all our chat about goodness and beauty and love and faith is mere decoration. That it’s just a layer of fake grass that we use to cover over the harsher, concrete facts of our existence.

Things like the basic violence of the natural ‘order’ and the raw power politics inherent in our competing systems. We even have a habit of bestowing the prefix ‘real’ on such politics.

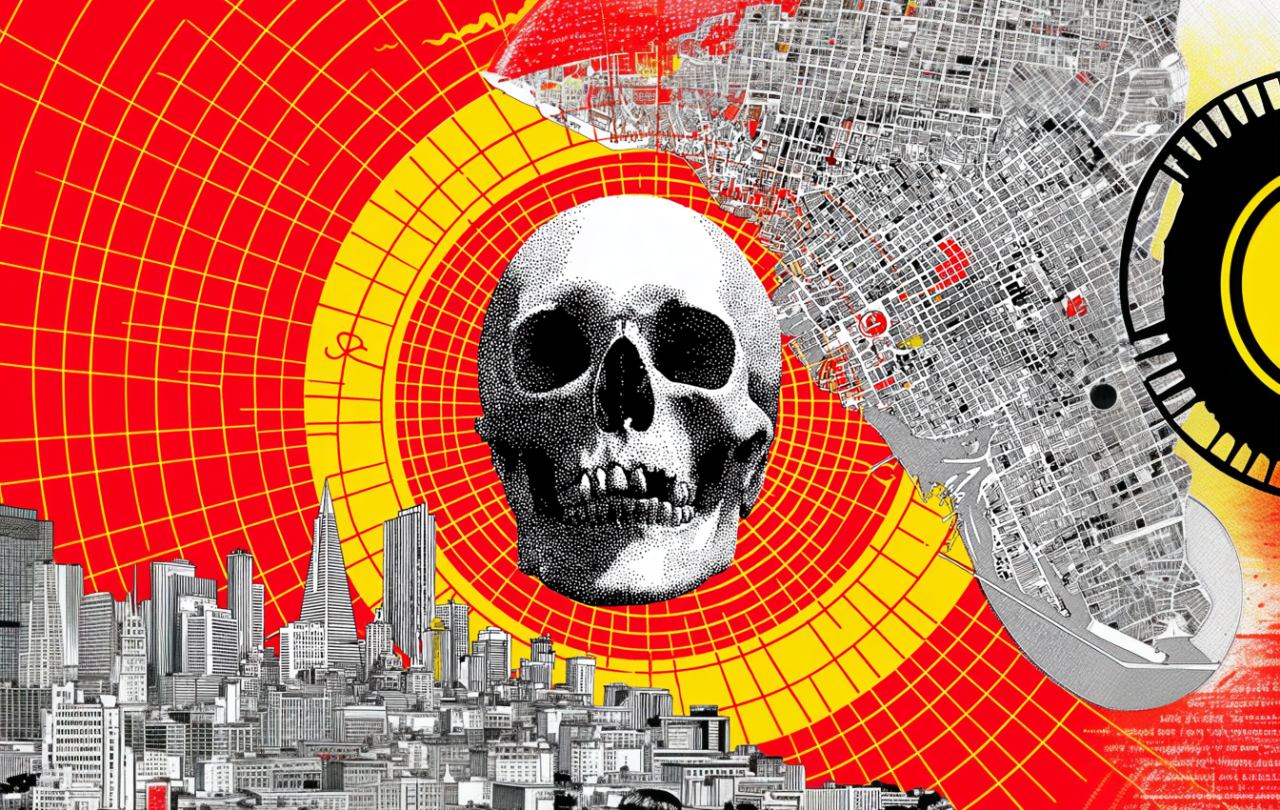

So is this ‘real’ stuff the concrete base layer of our existence? Is it the deepest truth? Is it the uncompromising reality that is always there, even as we prefer to cover it over with the fake grass of our stories of the beautiful and sweet songs of love?

Most of the evidence points that way: The stockpiles of nukes, the cutthroat colleagues, the succession of bullies intent on becoming the next big dog in the raw struggle for power.

I remember witnessing a violent assault at the tender age of eight. And the impact of encountering this ugliness on my young heart was a new shadow of fear. Suddenly the world was a colder and darker place. Then I grew up and became a priest. Which raises the question of whether I am spending my life just “whistling in the dark” to feel better? Am I just tending to the fake grass?

The celebration of Easter does not deny the darkness. It does not cover over the concrete. It claims, instead, that the ugly concrete base has in fact been cracked open to reveal a deeper subsoil, that there is something even more ‘real’, more true, more fundamental than the brutal struggle for power we currently all suffer within.

This is the high stakes of Easter.

it could be that our intuitions of beauty and experiences of love are, gloriously, not the stuff of fake grass and psychological coping mechanism

And here lies the deep and central significance of an obscure death on a Roman cross. It is the moment in which God, who is primordial love, faces up to the violent worst of murderous evil. Not with angel -armies to crush our sorry war-torn mess under a new almighty domination, which would only serve to confirm the lasting truth of the dark concrete layer, but by contradicting it, undermining it, through a humble death followed by resurrection.

I write it out and, to be honest, it is kind of surprising to me just how many people keep believing this unlikely story to be literally and deeply and seriously true.

It could be because most of us are not prepared to be as clear sighted as Putin (and all the others). That for some reason, we remain relatively unable to cope with being so brutally in touch with the cold, dark facts of the ugly concrete.

Or it could be that our intuitions of beauty and experiences of love are, gloriously, not the stuff of fake grass and psychological coping mechanism, but actually have their roots down deep into the subsoil of an infinite beauty and an ultimate love?

If so, it could also be that the strongest counter evidence available to us, countering all the nukes and bullies and violent domination, is noticing what lifts our hearts and moves us to tears? Beauty can do that. Violence cannot.

And so I keep whistling.