The Rave is a site for communal epiphany, a burst of divine revelation. Illegal raves and alternative club culture seeps into the popular imagination, informing it in ways unbeknownst to most. But it wasn’t until last Summer’s Brat (Charli XCX) landed on the global charts that people began questioning the importance of Rave and Club culture again. Is our Brat the herald of a new golden Rave dawn? I think not.

However, undergirding the Rave is something far more profound, perhaps even religious. Raving suggests that the world might be otherwise, and it does this through a temporary release from this world’s demands. What might this say about our cultural moment?

Coordinating the Rave’s aesthetic is the dance between the DJ and ravers, accentuated by the practicalities of a decent sound system, lights, and a bit of fog. Inaugurating Rave’s epiphany, though, are the diverse motions of bodies to a singular beat. Techno reduces digital sounds to their basics and then pushes that to its boundary. Circumventing the rigidity of technology’s logic are the gestures of human spontaneity on the dance floor. The rave asserts that technology doesn’t have the last say over human life.

At the Rave, those traditionally on the margins of society become the center: a temporal expression of eternal longing, momentarily experienced as a shared catharsis and liberation. The dance floor is a bulwark against an increasingly de-ritualised and dehumanising society. It is a testament to the body being a medium for hope. Whether an intoxicated body or, in a growing trend, a sober one, it is the human fleshyness which takes priority. Both options respond to how one might cope with and confront the technological barrage.

Techno began as a language for African American youth, finding a future amidst the industrial ruins of Detroit. In our late modern moment, Rave culture acclimatises the body to the persistent sound of our technological age. It subverts the dehumanising tendencies of digital culture: mass impersonal media and abstracted global conversations. Instead, a momentary online connection is used to gather offline. When you’re there, you’re not concerned about telling the world. It is an attention to the present moment.

The Rave harbours a liminal threshold between appreciation for this life and the longing for some next one.

Worryingly, some have warned that clubs will dwindle to their knees this decade, squeezed out by neighbouring property developers or no longer economically viable amidst the cost-of-living crisis. The only thing being pushed out, however, is the possible resistance to a particularly greedy homogenisation of culture. In dislocating alternative discourses of ritual, we simultaneously assert that human bodies only have one particular “rhythm”: the rhythm of ceaseless economic expansion.

The Rave resists an uncomplicated acceptance of technology’s gift. Its goods are re-scaled to an embodied celebration of life.

In Raving (2023), McKenzie Wark expands upon this, saying, ‘Techno, not as genre but as technique, lets digital machines speak. Not unlike the way jazz lets analog instruments speak… Sounds at the limit of what the machine or the instrument can do to get free. Blackness in sound as the technique of making the thing free to sound off as itself and to take the human with it, into movement, into feeling, into sensation.’ Rave’s sound quite literally brings technology’s language to the end of itself.

For some, raving is what holds them to life. For others, it’s a momentary release from it. Whilst our bodies cannot exceed techno’s interchange with technology, we do learn how to harness the potential humanness within it. The Rave harbours a liminal threshold between appreciation for this life and the longing for some next one. In twisting its technological medium into a more human configuration, rave culture participates in hope.

Back in 1965, theologian Jürgen Moltmann wrote, ‘Hope’s statements of promise, however, must stand in contradiction to the reality which can at present be experienced. They do not result from experiences, but are the condition for the possibility of new experience… They do not seek to bear the train of reality, but to carry the torch before it. In so doing they give reality a historic character.’ While Moltmann is writing concerning Christianity and the crucified Christ, his framework for thinking about hope is helpful. Hope never occurs outside of history. The Rave embraces this historical moment and attempts to inhabit it as a contradiction.

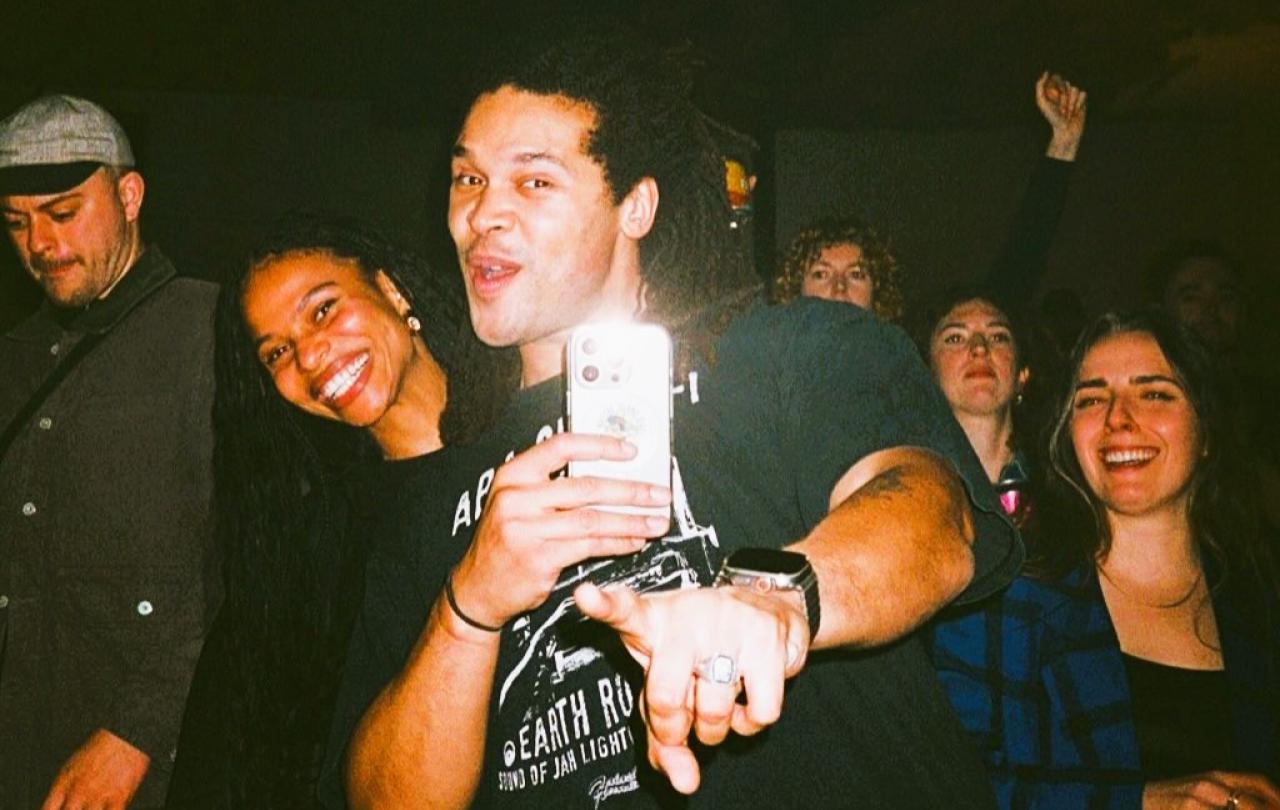

Recently, I went to Rhythm Section International’s tenth-anniversary party at EartH, Hackney. Rhythm Section was founded as a music collective and is still curated by Peckham’s own Bradley Zero (BZ). Known globally, its parties and label imprint span techno, house, jazz, funk, spoken word, and RnB.

I first danced to BZ’s DJing at a record shop in 2018 while still living in Melbourne. The beauty of this particular community is that it provides a bridge for what Wark identifies: just as jazz brings analogue instruments to their limits, techno does the same for digital. As experienced recently at EartH in Hackney, Rhythm Section tries to push digital and analogue sounds to their threshold across the night. In contrast to the pure techno rave, BZ’s selection causes a polyphonic liberation. Joy is found through the instruments slapped just as much as in the DJ faders pushed.

This joy was evident in the diversity of ages and cultures present. “Mature heads” danced alongside students; some swayed, while others vogued. Without spaces such as these, where else can we celebrate the diversity of human responses to the same sound?

My concern with club culture’s demise is that those places of contradiction are swallowed up by a faux vision of “smoothness”. We replace spaces of alternative being with sameness. A diversity of aesthetics is converted into another apartment complex. We make room for the novelty of Brat but not the culture she draws upon.

Rave culture attempts to redefine the dominant technological language of our day, making the body its lens and not the periphery. By privileging the human body, Rave’s hope acknowledges profound discontent with the world but understands that all “escape” is temporary. This re-calibration enacted in Rave’s ritual de-escalates the supposed importance of technology’s ceaseless expansion. Thus, it exposes a more profound longing, one where it will be an eternal dance that deepens the love of life by going ever deeper into the particularities of individual bodies and their movements.

Because it offers a form of explicit hope, the Rave is a ritualised space filled with the belief that there can be “something more”. And this more-ness is, ultimately, encountered in the face of those we dance with; whether in a fleeting glance to ask, “Are you alright?” or the mutual smile that says, “I love this song”.

Join with us - Behind the Seen

Seen & Unseen is free for everyone and is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you’re enjoying Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Alongside other benefits (book discounts etc.), you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing what I’m reading and my reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief