‘Waiting to Speak to Milton’ shows the artist Richard Kenton Webb on a rain-swept night waiting in a valley for a car whose headlights can just be seen at the crest of the hill. For this image he has imagined himself waiting for a lift from John Milton to discuss the poems Paradise Regain’d and Samson Agonistes. As the opening image to Webb’s exhibition at Milton’s Cottage in Chalfont St Giles it is appropriately positioned in the porch by which visitors enter the cottage.

This image of light appearing in the dark night of the soul symbolises the beginning of Webb’s journey with Milton and his late poems Paradise Lost, Paradise Regain’d and Samson Agonistes. This has been a 10-year journey that Webb began following a conversation with his son in front of John Martin’s mezzotints for Paradise Lost at the Tate. Following on from his son’s encouragement to begin work, over that period, Webb says Milton has been a companion like Virgil to Dante guiding him through the narrative of his own life including the dark nights of redundancy and lockdown. The result has been 128 drawings, 40 paintings and 12 relief prints forming A Conversation with Milton’s Paradise Lost, a commission of 12 drawings in response to Milton’s pastoral elegy, Lycidas, for the Milton Society of America, and the 13 drawings forming this exhibition, A Conversation with Paradise Regain’d & Samson Agonistes.

Milton proved an effective companion because he, too, had passed through his own dark night of the soul. He arrived in Chalfont St Giles to escape the Great Plague of 1665 after the Republican cause to which he had dedicated more than a decade of his life - being Oliver Cromwell’s unofficial spin doctor - had collapsed around him with the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660. He had been lucky to escape with his life following imprisonment and the banning of his books. In addition, he had lost his sight, his beloved second wife, much of his money and all of his influence.

Despite these traumas, Milton was able to express his love for his Creator wonderfully in Paradise Lost, which was completed at the cottage in Chalfont St Giles, and Paradise Regain’d, which was inspired whilst there. In both Paradise Regain’d and Samson Agonistes Milton deploys his rich verses and visions of spirituality and the forces of good and evil to reflect on the Restoration of the Monarchy and the loss of the English republic, doing so by means of Biblical stories concerning Jesus and Samson.

Browse Webb's exhibition

In Webb’s view, “Paradise Regain’d is about overcoming impossible situations” while, in Samson Agonistes, Milton’s Redeemer shows “Samson, the blind and foolish man”, “that we can always find hope in our living God even when society does not”. These poems moved Webb out of despair to discover hope because he knew they were heading towards redemption. As a result, he sees Milton as “a great English poet who gives hope, which in itself is a creative act for these difficult times”.

Although the story of Samson pre-dates that of Jesus being tempted in the wilderness, Webb’s painting series begins with images inspired by Paradise Regain’d, just as Samson Agonistes followed Paradise Regain’d when both were jointly published in 1671, because Jesus’ resistance of temptation ultimately redeems those, like Samson and Adam and Eve, who were unable to resist.

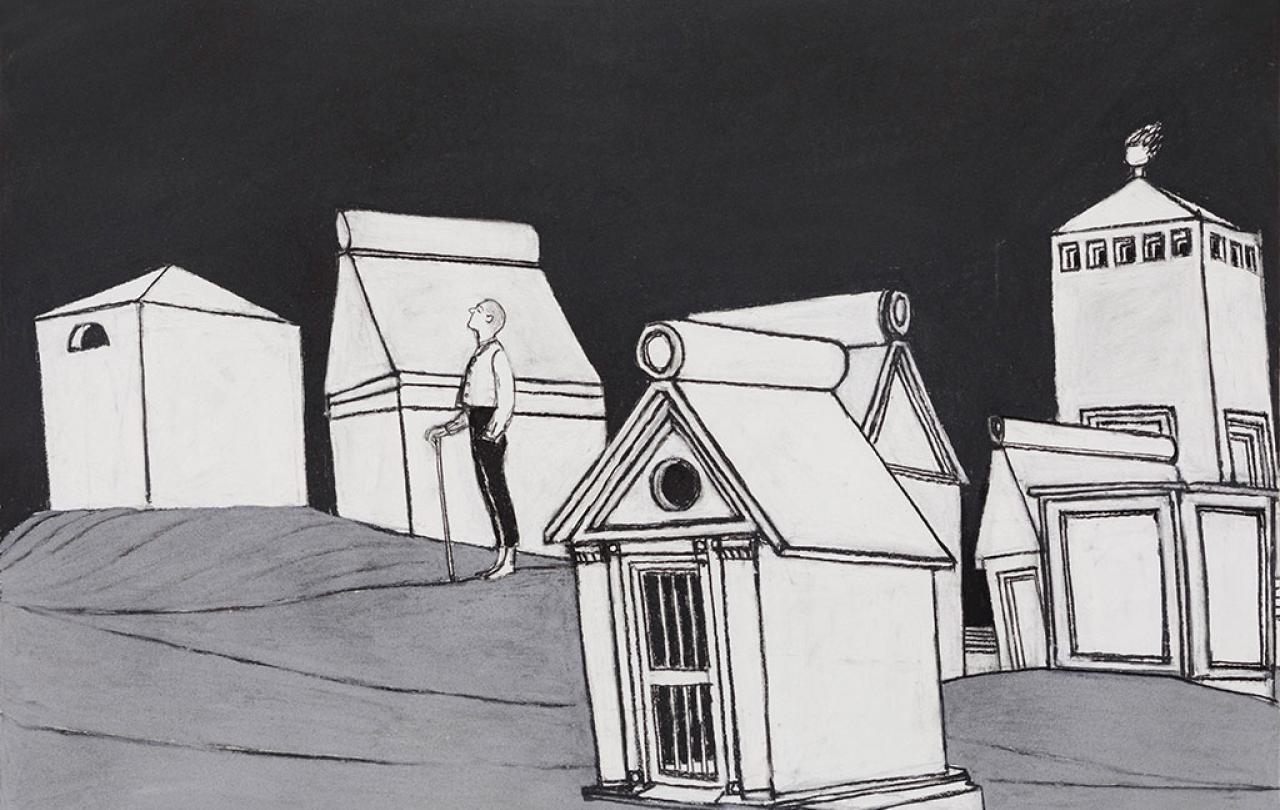

These are images set against a dark background with the exception of the final Paradise Regain’d image with its white sky depicting a paradise within as Jesus has overcome temptation, is in full communion with God and is about to begin his ministry by calling his first disciples. The images move from the trauma and test of temptation – whether involving hunger, greed, lust, threat, pride or ambition – to a calmness of mind that is equipoise and liberation and which also enables the destruction of false temples.

They are images in which movement is arrested in still moments which form theatrical tableaux. These, like medieval and early Tudor morality plays, involve the viewer in an epic struggle between good and evil, involving temptation, fall and redemption. Webb’s use of charcoal and white chalk on paper emphasises the binary nature of this struggle. Being formed of charcoal and chalk, despite his use of contemporary equivalents for the temptations, the look and feel of Webb’s images also accords well with their exhibition setting, in rooms of low ceilings, uneven white walls, dark beams and furniture.

Webb’s works and exhibition also universalise Milton’s own experience of the dark night of the soul by merging that story with Webb’s own.

As Paradise Lost was the first illustrated poem in the English language, Milton’s poetry has, as Kelly O’Reilly, Director of Milton’s Cottage, has noted “inspired many of our greatest artists, from Blake to Turner, Dore to Dali”. Webb, who consciously works in the continuing tradition of Blake’s visionary art, is extending the tradition of illustrating Milton’s poems. It is appropriate, then, that, by exhibiting these drawings in Milton’s Cottage, they are placed alongside examples of illustrated editions of the poems, plus other paintings and prints relating to Milton.

Milton’s works are not only a repository of rich verse, which also gifted over 600 new words to the English language, but are also a conversation with scripture, its stories and their interpretation, plus the social and political ramifications of the Reformation in the British Isles. Webb’s works and exhibition also universalise Milton’s own experience of the dark night of the soul by merging that story with Webb’s own and linking those powerfully to the themes of Milton’s poems.

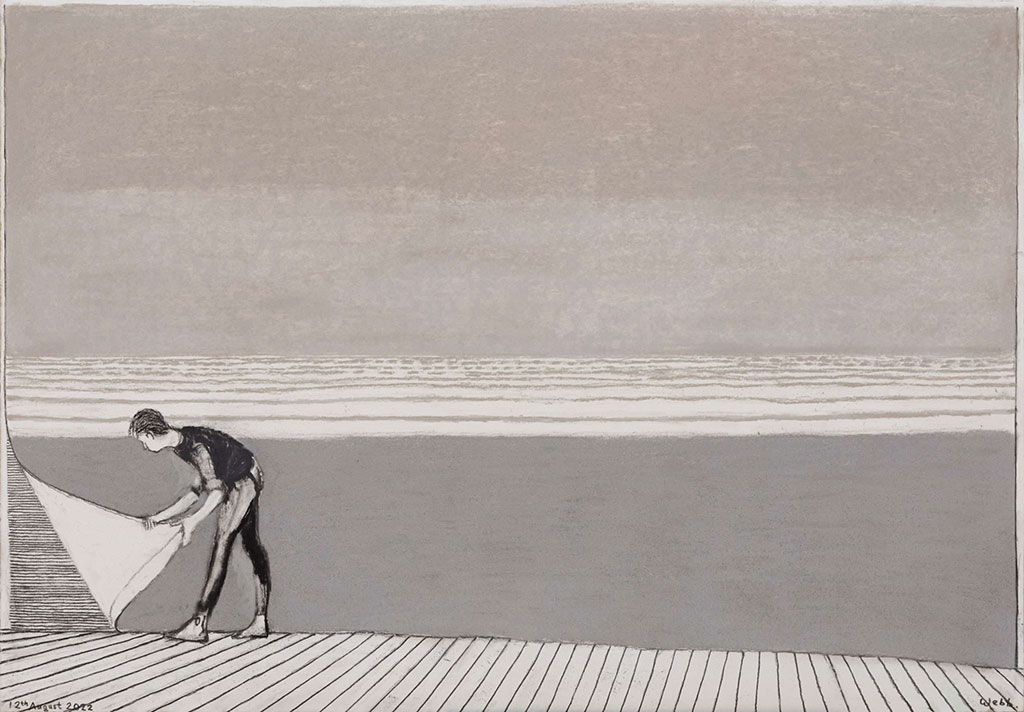

The key image, in this regard, is the first in the Paradise Regain’d series (‘Modes of Apprehension’), which sees Jesus in the wilderness turning up the corner of the wilderness backdrop, as in a theatre, to reveal another dimension or reality to existence and experience behind it. Hope is discovered in the midst of desolation, resilience found in the face of temptation. In these ways, Webb achieves his own hope for these works, that, “by responding to Milton’s universal themes of creation, destruction, temptation, love and loss”, he “can help new audiences find fresh ways to engage in Milton’s legacy”.

A Conversation with Paradise Regain’d & Samson Agonistes, Milton’s Cottage, 3 July – 8 September 2024.