2011: London’s Westminster City Council proposes byelaws to ban rough sleeping and to prevent groups distributing food to people in need, known as ‘soup runs’, in the Victoria area.

The proposals caused an almighty uproar from charities and community groups and demonstrations outside the council offices. In addition, both the London Mayor Boris Johnson, and the Conservative central government spoke out against the plans. In the end the proposals were quietly withdrawn.

At the time I was Director of the West London Mission, a homelessness charity based in Westminster. We worked closely with both churches and the council but we publicly disagreed with the plans because they were divisive, polarising and unworkable.

‘Lifestyle choice’

2023: The Home Secretary, Suella Braverman, makes comments on social media about cracking down on rough sleepers who sleep in tents. Among other comments, Braverman said:

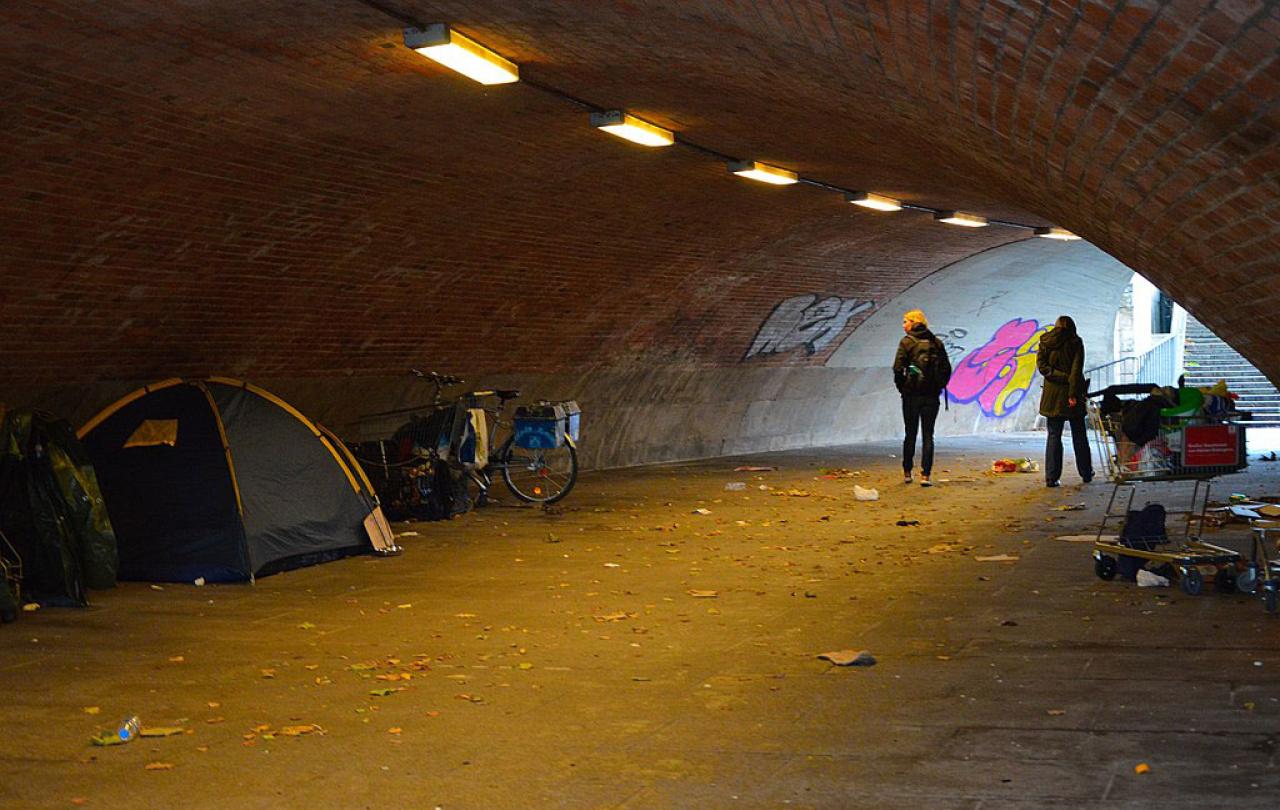

"We cannot allow our streets to be taken over by rows of tents occupied by people, many of them from abroad, living on the streets as a lifestyle choice.”

Again, Braverman’s comments have provoked an avalanche of criticism. In the middle of a housing and cost of living crisis, the accusation that people living in tents are simply making a ‘lifestyle choice' is rightly seen by many as simplistic, harsh and deeply unhelpful to addressing the serious issue of rough sleeping.

Nothing represents UK poverty and exclusion with such visceral power as the sight of someone huddling in a doorway. Therefore, to the average person, providing help to rough sleepers makes sense. Banning help appears harsh and inhumane. These are issues that need talking about carefully and compassionately.

After 25 years of working for homeless charities, I worked for four years in the Government’s Rough Sleeping Initiative as an Adviser on how faith and community groups addressed homelessness. Building trust and cooperation between charities, churches and government was the key focus of my work.

And probably the most sensitive of all issues is how the outdated ‘Vagrancy Act’ of 1824 could be replaced. I know what frustration the Home Secretary’s ill-judged comments will cause to those in government working hard on reducing rough sleeping.

Dangerous and insecure

But whilst it’s right to condemn Braverman’s comments, we have to consider how we respond and not simply add to the unhelpful polarisation of these issues. The answer to anti-tent rhetoric is not to encourage people to give out more tents.

It may sound obvious, but the key thing to focus on is the welfare of rough sleepers at the heart of this discussion. And that does not mean we endorse every form of help that is offered.

The truth is that the rise in the use of cheap tents to sleep rough in is a genuine problem that local councils and charities have been struggling to address. They often create dangerous and insecure environments and can easily mask people’s serious declines in physical and mental health.

Christian response

A few years ago, I worked closely with All Saints Church in the centre of Northampton because they had 15 tents pitched in their churchyard. The drug use, defecation and other behaviours of those living in the tents were genuinely anti-social and problematic. Tensions with the council were rising and the vicar, Oliver Coss, was grappling with what the right Christian response was. Of course, there was genuine housing need in the town but what was happening in his churchyard was no good for anyone.

Through careful discussions, we brokered a plan of joint action between the church, the local authority and the key local charity. Those sleeping rough in the churchyard were given notice and were told the tents would be removed on a certain date but alongside this, interviews and offers of housing were made to everyone. I have huge respect for the way Rev.Coss navigated these tricky waters with resolve and compassion. He took heat, especially when the national press picked up the story but he steered a course which was genuinely best for all concerned. Theologically, his actions were the right blend of grace and truth.

Relationship and trust

Last winter I was involved in a similar way with an encampment in the park right behind my house in south London. It was causing serious concern to many local people due to the fires being lit, rubbish piling up and the vermin it attracted. I got to know almost all of the occupants of the camp as they attended a drop in meal I run at my church. The relationship and trust we developed helped me liaise between them and the council’s rough sleeping coordinator and this led to the camp being cleared and each of them offered temporary accommodation.

Informed debate

Rather than hasty policies or silly soundbites, we need a more honest and informed public discussion about rough sleeping. Addressing homelessness is complex because it involves an interweaving of structural injustice and the personal challenges that individuals face. Simplistic comments may work well on social media, but they don’t help people in the real world.

Enforcement is not the dirty word it is often made out to be – sometimes it is a vital ingredient in helping someone change their life. But in order to work, it must always be accompanied by a valid offer of accommodation, a meaningful step off the streets. And for too many, especially non-UK nationals, no such step exists.

Radical reform

Housing should be the key issue in the next election. We need urgent and radical policy reform to build more social housing. Record numbers are housed in expensive temporary accommodation which is causing bankruptcy in some local authorities. Millions of pounds of public money has been wasted in housing people for years in hotels which could have been used so much more productively.

We need more of the longer-term, community-based solutions to homelessness such as those pioneered by Hope into Action. We attract investment to buy houses which we turn into homes for people who have been homeless. In addition to professional support, each house is connected to a local church who provide friendship and community.

People sleeping rough in tents is not a ‘lifestyle choice’. It is the visible tip of a vast homelessness iceberg in this country caused by relational poverty and chronic underinvestment in affordable housing. And if we do not address the problems beneath the waterline, then we should not be surprised to see more tents appearing in our towns and parks.