One in four. This is the number of people living in conflict-affected areas on this planet. A record 100 million people have been forcibly displaced worldwide. Psychologists tell us that we can only process numbers in the two-digit realm in a meaningful way. Any number larger than that eclipses our capacities to attach a face, a story, an existence to that number. 100,000,000 is simply too large to picture. So imagine the entire UK population on the run, plus the population of Australia, plus that of Hongkong. In 2022, 16,988 civilians were killed in armed conflicts, which is a 53 per cent increase compared to the year before. And as you read these lines, there are 32 ongoing violent conflicts in the world, including drug wars, terrorist insurgencies, ethnic conflict, and civil wars.

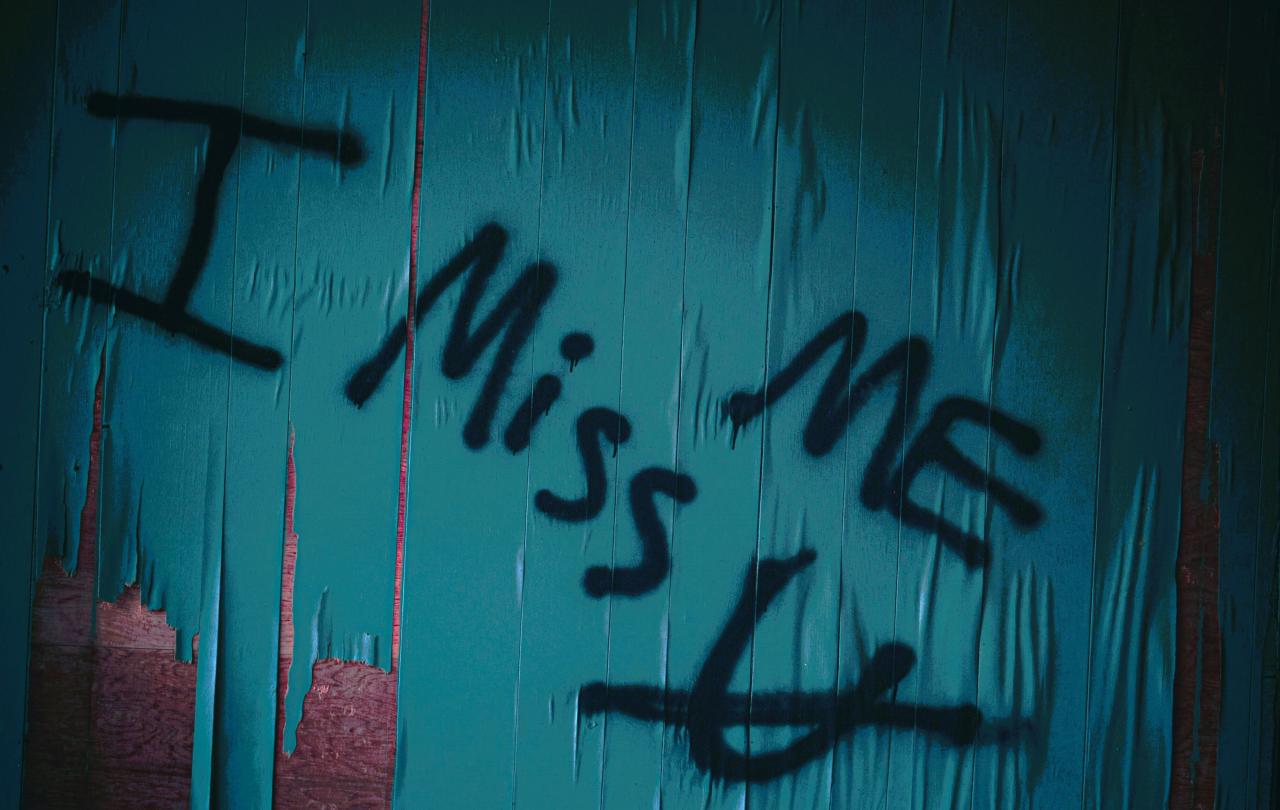

Just as we are overwhelmed with trying to grasp the extent of violence, conflict and war, we are equally at loss with imagining peace. When in 1981 the United Nations General Assembly established the International Day of Peace (IDP), it was recognizing exactly this by emphasizing that “it is in the minds of men that the defences of peace must be constructed”. Constructing, envisioning, imagining. The tough world of realpolitik, however, seems to leave no place for such kind of romantic games of mind. Helmut Schmidt, former chancellor of Germany, made no attempt to hide his scorn for the imaginary, “Let him who has visions consult a doctor”. This shows a remarkable misconception of reality, however. French philosopher Henri Bergson points to the power of imagination, for to invent “gives being to what did not exist; it might never have happened”. Perceiving and transforming reality thus become mutually supportive forces. And the numbers above make it clear that peace is not the default option of reality, but needs to be envisioned. “Inventing peace”, as film director Wim Wenders calls this conscious effort.

Restoring momentum to the SDGs is a crucial sign of life for global cooperation – and for peace.

So peace begins in our minds, but it cannot remain there. Just as love yearns to be embodied, peace seeks concrete shape. And just as the shape of love is acts of kindness, the shape of peace is acts of justice. In the Jewish and Christian tradition, the term shalom is used to convey this kind of inclusive vision of peace and justice. This year’s International Day of Peace (IDP) coincides with the UN General Assembly. When conceived 78 years ago, a vital part of the United Nations’ raison d'être was the common vision for peace. The experiences of the horrors of two world wars totalling more than 76 million people dead – another one of these unfathomable numbers –united the nations of this world in their quest for peace. Yet the shape of peace is justice. So three years after the conception of the UN, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was born, celebrating its 75th birthday this year.

As the world leaders currently convene for the UN General Assembly, however, the nations assembled there will be anything but united. The demand and supply of international collaboration seem grossly disproportionate as multiple challenges, including geopolitical, ecological and economic crises, eat away on multilateral ties. This year’s IDP also coincides with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) summit, marking the mid-point milestone of the goals.

Endorsed in 2015, the 17 SDGs unfold the vision of a better world, including the eradication of poverty, advancing education and gender equality and environmental stewardship. If justice is the currency of peace, it seems only appropriate that this year’s IDP’s theme is ‘Actions for Peace: Our Ambition for the #GlobalGoals’. “Peace is needed today more than ever”, says UN Secretary-General António Guterres. This, in turn, means that the vision spelt out by the SDGs is needed today more than ever. It is a misunderstanding to conceive of the SDGs as an add-on for better times. Rather, restoring momentum to the SDGs is, as Stewart Patrick and Minh-Thu Pham from the Carnegie Foundation point out, a crucial sign of life for global cooperation – and for peace, one may add.

To dispel the ever-prevalent “myth of redemptive violence” as the still predominant paradigm, we need exactly this kind of active imagination.

One would think that the scale of the challenges spelt out by the 17 SDGs requires the joint collaboration of all actors. Yet one factor that is strikingly absent in this equation is religion. This is all the more remarkable given the fact that 85 per cent of this planet’s population profess adherence to a faith tradition, according to the World Population Review 2022. This makes faith communities the largest transnational civil society actors. Now religion – every religion – is inherently ambivalent. But this means that each religion can not only be used to incite hatred and violence, but also contains potent resources for peace and reconciliation.

Many of the SDGs including peace, justice, equality and care of creation to name but a few align with core concerns of, for example, the Christian faith tradition. Just imagine the potential for transformational change towards peace and justice if faith-based actors worked together, among each other and with secular actors! To dispel the ever-prevalent “myth of redemptive violence” (Walter Wink) as the still predominant paradigm, we need exactly this kind of active imagination. Or as the poet of an ancient song once put it:

“Kindness and truth shall meet; justice and peace shall kiss”.

For more information on the role of religion in the SDGs, read the Open Access book series “Religion Matters. On the Significance of Religion for Global Issues” (Routledge), edited by Christine Schliesser et al.