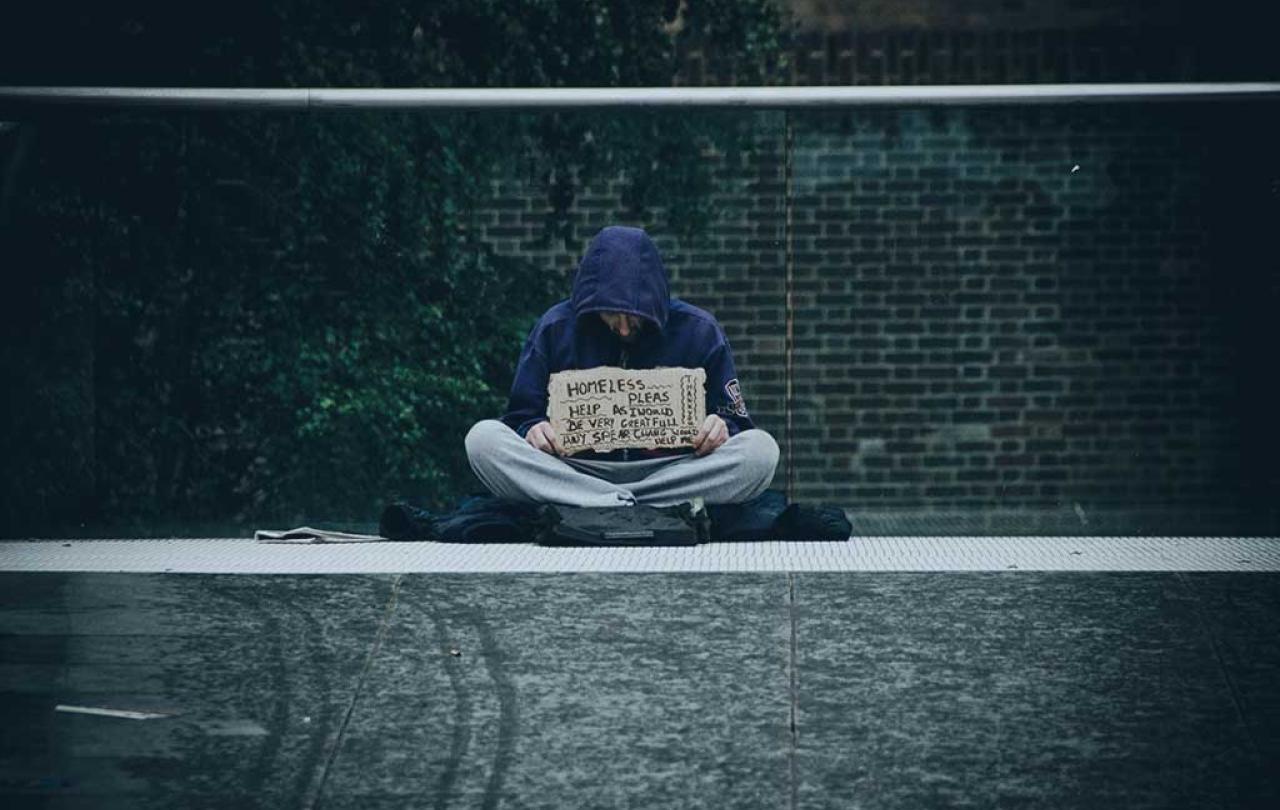

Recently I was in Birmingham New Street station when a man approached me, saying he was homeless and asking for money for food. We were right next to a Greggs so I suggested I buy him some. As there was a queue, we got talking and he said:

‘I’m not really homeless you know, I’m just so bored and I live in a s**t-hole.’

For many people living or working in towns and cities, being asked for money like this is an everyday experience. It can often cause feelings of distress, guilt and confusion. What is the best way to respond to someone asking you for money? In thirty years of working with people affected by homelessness, it is by far the most common question I have been asked.

Earlier this month, Matthew Parris wrote in The Times about his experience of giving £25 to someone begging after being told they needed money for an urgent train ticket. The following week he saw the same person using the same story and he realised that he had been suckered. It is an experience that many of us might relate to.

I used to be the manager of an emergency hostel for young homelessness people in Soho in central London. Most of our residents had complex problems which were complicated and intensified by drug addiction. Begging was a key source of income.

Some residents used the duvets that we gave them as begging props to indicate they were sleeping rough. We would often overhear them telling passers-by that they ‘needed money to get into a hostel’. Often, they could raise large sums of money based on their articulated need for food, accommodation or travel. But none of the money was ever used for these purposes.

Matthew Parris is right when he writes ‘begging and sleeping rough bother us tremendously.’ They are some of the most obvious and visceral indicators of poverty and this ‘bother’ gives the issue considerable political capital. As Parris says:

'Any minister or prime minister who could associate their name with making a visible difference would reap a harvest.'

We need a compassionate realism about the nature of the problems which surround those who beg and honesty and bravery about how best to respond.

But as well as high profile, homelessness and begging are both very sensitive issues. Thankfully, gone are the days in the 1980s when newspapers like The Sun would routinely describe those who sleep rough and beg as ‘dossers’. Today, the public discussion is couched far more sympathetically, but this change in tone can create difficulties in talking honestly about the reality of begging. It can be a minefield where those cautioning against giving money can easily be viewed as mean-spirited or judgmental.

We need a public discussion on begging which avoids the unhelpful polarization between naïve compassion and harsh cynicism. Neither of these help anyone. And we should remember, that whilst we should avoid judgementalism, we cannot help people effectively without showing good judgement. We need a compassionate realism about the nature of the problems which surround those who beg and honesty and bravery about how best to respond.

We live in a time of severe economic and housing injustice. The years of austerity, cuts to public services, the pandemic and now the cost-of-living crisis have all deepened the challenges for poorer communities. Our country urgently needs to address the chronic shortage of affordable housing.

But does this rise in wider poverty mean that we should give money to people begging? My answer is ‘No’, because I don’t believe that it is an effective way to help people. These are my reasons.

The material need and physical destitution are symptoms of the deeper issues of trauma, poor mental health, broken relationships and the addictions.

Firstly, it is important to remember that the issue of rough sleeping and begging are related but are not the same. Many of those who beg are not sleeping rough, and the majority of homeless people do not beg. In fact, begging has much more of a direct link with addiction or criminal gangs than it does with rough sleeping. In the last 10 years there has been a growth in the coordinated use of immigrants, many trafficked, to beg in city centres. Your cash donation will not truly help the person.

Secondly, we need to appreciate that immediate material resources are not the key problem for people begging. Whilst there is a deepening crisis of poverty in the UK, there are many day centres, charities and community groups offering emergency food and clothing. The material need and physical destitution are symptoms of the deeper issues of trauma, poor mental health, broken relationships and the addictions which have developed in response. These deeper problems are often compounded, rather than helped, by gaining money through begging.

Thirdly, we need to focus on the true needs of the person begging rather than on our need to respond. Our feelings of awkwardness and guilt may be assuaged by handing over money, but this does not mean that what we have done is right. The temporary ‘feel-good feeling’ is not to be trusted. If more people gave money to people begging then it will not result in a more just world. Allowing untruthful and manipulative behaviour to succeed in eliciting cash helps nobody. It can literally be ‘killing with kindness’.

Fourthly, we need to recognise the lack of truth in the exchange between someone begging and a potential donor. Often a scenario presented is designed to place emotional pressure on the hearer to do what is being asked. For example, that money is needed to pay for a hostel bed, to get a hot meal or travel money to see an ill child. But hostels and shelters for homeless people do not charge on the door - they are either free or the rent is covered by housing benefit. In my experience, the vast majority of the scenarios presented in the begging exchange are simply not true.

Underneath these points are key principles around how we help others. Despite the retreat of Christian faith in public life, the injunction to ‘love our neighbour’ is still a foundational one in our society and culture. And authentic love is always made up of both grace and truth.

Our instincts to show compassion and care are part of what makes us human. We are moved and motivated by seeking to address suffering and hardship. We have a desire to show grace to those suffering.

This does not mean being cynical. Authentic change is possible, and I see it every day.

But this grace must remain connected to truth. We must take responsibility for how our instinct to show grace can be manipulated. The reason that begging is never a positive aspect of someone’s recovery journey is because it is a transaction rarely based on truth.

We may long for a simplistic world where good intentions are enough and where all donations given in good faith are well-used, but this is not the world we live in.

This does not mean being cynical. Authentic change is possible, and I see it every day at Hope into Action. We help people who have been homeless by offering them a quality home with both professional support and befriending in partnership with a local church. Last year we housed over 400 people and it’s a privilege to walk with people and help them on their journey of recovery. One of our tenants said to me:

‘Hope into Action didn’t just give me a ladder to get out of situation, they showed me how to build my own staircase.’

The best services for homeless people show grace in their acceptance and welcome, but from this base they explore the truth about the challenges people face. And truth is a key ingredient in all effective recovery, counselling and rehabilitation programmes.

Change is possible but truth is always a critical ingredient. It’s the truth that sets people free.

How should we respond to someone begging?

-

When someone begs from you, look them in the eye when you respond and speak as confidently as you can.

-

If you have time, stop and talk with them. Ask them their first name and share yours.

-

If you have the time and money, offer to buy them a cup of tea, or some food.

-

Research what drop-in centres, charities or churches are open for vulnerable people in the area where you live or work. Knowing what is available allows you to ask the person if they know about these and whether they have used them.

-

If you are worried about the vulnerability of someone sleeping rough then contact Street Link on 0300 500 0914 to inform them. This is a coordinated phone line which informs the local homeless outreach teams.