The careers of artists rarely progress in a simple linear fashion. That was very much the experience of Alastair Gordon in 2024. Gordon is co-founder of Morphē Arts, a painter, art tutor at Leith School of Art and a contributor to Seen & Unseen. He works from his studio in South London and exhibits with galleries and art fairs across the UK, Europe and the US. His experience in the past year opens up fascinating avenues into guidance, focus and prayer.

He says that: “In many ways, I achieved none of the goals I set for myself last year. I didn’t generate more income in the studio than the previous year, I wasn’t invited to exhibit at the prominent LA gallery I had in my sights, and I didn’t make it into Modern Painters magazine.

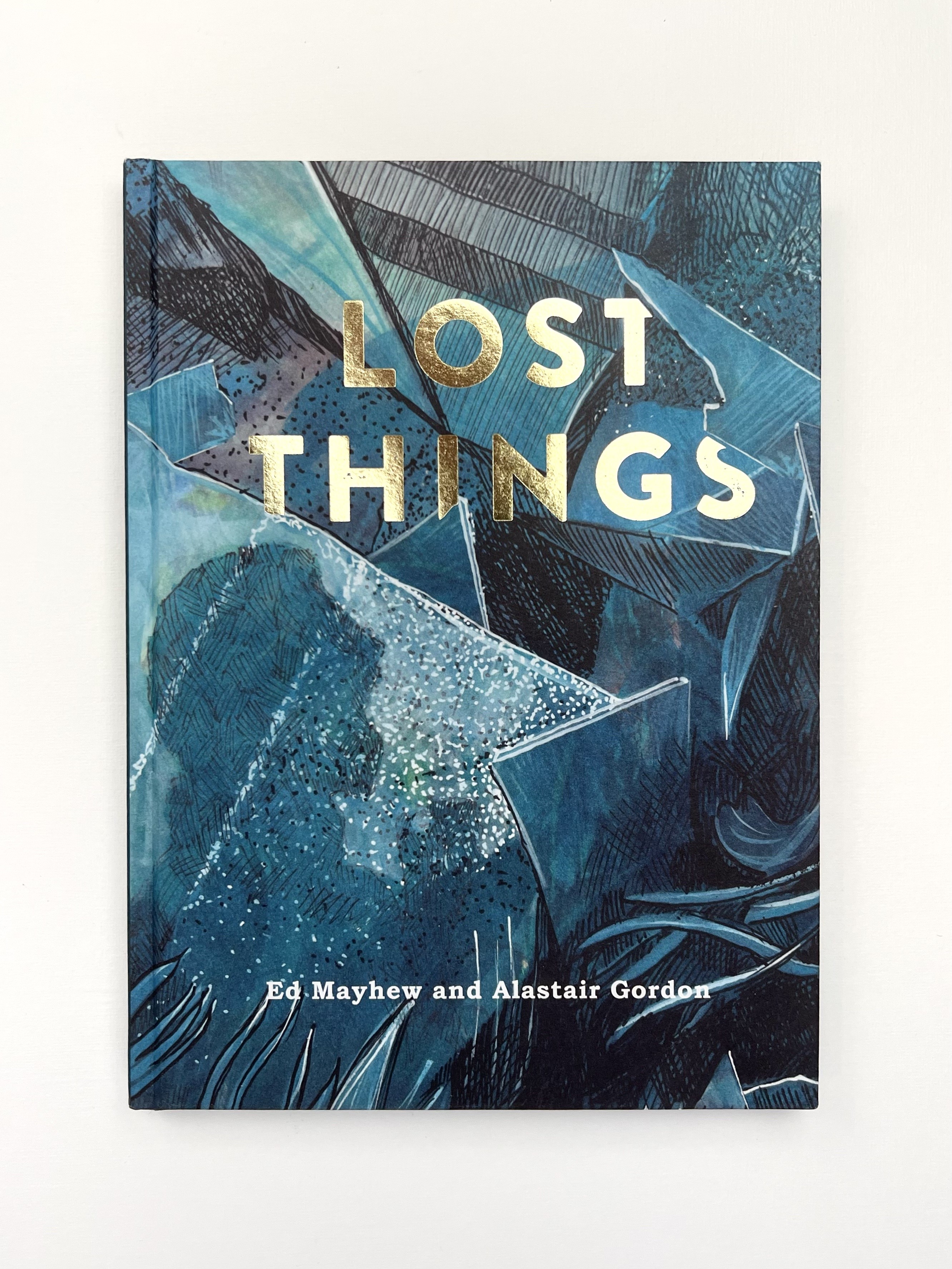

Yet, I had an extraordinary year exhibiting that excelled my expectations. Exhibiting at An Lanntair Gallery in the Outer Hebrides marked my first museum show. I completed my first public commission for a church in South London, and my fourth book, Lost Things, co-written with the wonderful poet Ed Mayhew, is ready for release next month.

This past year taught me a valuable lesson about not fixating on goals as defined by the art world. Instead, I learned to focus more on what truly matters: the work that really matters and the people I hope to connect with through my painting.”

One of the surprising opportunities that came to him in 2024 was a commission to paint for a church. He says of this that: “It was a wonderful opportunity to create a painting for All Saints, Wandsworth. It’s unusual to have the chance to make a large work that resonates so deeply with my Christian faith. The painting is centred around the theme of prayer, and I aimed to draw on art historical references to prayer while incorporating the prayers of the current church congregation.

When I was working on the imagery for 'Prayer of the Saints,' I focused on key ideas related to the prayers of the church congregation—past, present, and future. Commissioned to complete the nine vacant panels in the chancel, I faced a unique compositional challenge.

The motifs of olive leaves, lilies, white roses, pebbles, and feathers symbolise quiet petitions to God. The central panel features an open Bible to Philippians 4:6, accompanied by a handwritten journal with a sketch of a stained-glass window and a prayer of Augustine, as well as a broken mobile phone that represents a longing to communicate.

I included images of Wandsworth, Wimbledon, and Battersea to reflect our prayers for the local community, alongside portraits of current missionaries and a world map highlighting our prayers for God’s mission abroad. A portrait of a cherished brother who died young serves as a poignant reminder of our prayers for lament and hope.”

As a result, he says: “The painting features flowers like white roses and lilies, which are often observed in Western art as symbols of prayer, alongside images of the local community, held in reverence by the congregation and the missionaries they support worldwide.”

The philosopher Simone Weil suggested that attention, taken to its highest degree, is the same as prayer. Gordon says that this insight on attention and prayer resonates deeply with his experience as an artist: “When I engage fully in my work, that heightened attention feels like a form of prayer.”

Looking at the overlooked is central to my artistic practice. I feel a resonance with artists of the past who have focused on the everyday moments.

His latest book project, a collaboration with Ed Mayhew, touches on similar themes: “It started with a glimmer. Two years ago, Ed sent me a poem and asked if I would like to create a painting in response. It was the most beautiful poem and an enticing invitation. I made a painting and sent it back to him. He replied with another poem, and I responded with another painting. This back-and-forth continued, and before we knew it, we had created 25 poems and paintings in collaboration.

The connection between words and images was foremost in our thinking for this project. I didn’t want to illustrate so much as to respond to Ed’s words through paint and drawing. Similarly, when Ed returned my paintings with words, he aimed not so much to describe but also to converse. Our hope was to create an equal exchange between word and image, allowing each to complement and enhance the other.

Lost Things is a precious collaboration. We are very grateful for this partnership and the unique book it has produced. Lost Things explores all the things that go missing in life, the hopes we have for their return, and the love we share for the overlooked. This book explores the oddities that have been misplaced or forgotten—strange objects that wash up on the shore, appear in your sock drawer, or disappear into the loft for decades. It also reflects on the people we have lost or forgotten. In this way, the book takes a playful approach while also pointing toward deeper truths.

Paying attention in this way to what others have overlooked or lost seems very much the task of artists: “Looking at the overlooked is central to my artistic practice. I feel a resonance with artists of the past who have focused on the everyday moments that might otherwise go unobserved. Most often, it’s the mundane objects that have become so familiar that they almost become invisible.

Focusing on details—colours, shapes, emotions, and often overlooked objects—allows me to connect with something greater. It feels like speaking in tongues; the act of creation transcends words and expresses something less tangible. At times, the meaning isn’t clear, and I need to wait for it to be revealed.”

All this would seem to have been very much the case in the past year, where unanticipated opportunities led to wonderful work and exciting new projects.

Join with us - Behind the Seen

Seen & Unseen is free for everyone and is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you’re enjoying Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Alongside other benefits (book discounts etc.), you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing what I’m reading and my reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief