The opening ceremony of the 2024 Paris Olympic Games, held on the River Seine, has unsurprisingly caused controversy. Such moments, where one nation through pageantry and spectacle performs itself to all others, never fail to draw comment. The 2024 ceremony has drawn various detractors, not least those claiming the ceremony was an “attack on Christianity.”

You might remember the masterful opening to the London 2012 games. Director Danny Boyle’s theatrical spectacle told a symbolic story of nationhood. By depicting the bucolic, the industrial, and the NHS, he considered the UK in both dark moments and at its brightest. With a great exhibition of British humour, James Bond appeared to parachute out of a helicopter with HRH Queen Elizabeth II, while Mr Bean entertained the whole wordlessly through sardonic single-finger piano playing.

Widely held to be a creative triumph, Boyle was preceded by the Beijing Olympics where its opening ceremony, CGI fireworks put to one side, wowed the world with unprecedented size and scale, reminding us that we live in an era of Chinese power.

Tokyo 2021, delayed by a year due to the Covid-19 pandemic, involved 1,800 drones filling the skies – a faultless demonstration of a technological age where Japanese engineering has been indispensable.

The sporting side of things was easily forgotten as we witnessed an emphatically kitsch depiction of French history and culture.

In 2024 Paris, the weather was perhaps the greatest focus of attention, which suited the British commentary perfectly. We Brits surely are the world experts in making light-entrainment out of describing rain. Soggy athletes sailed the Seine on a variety of uninspiring looking barges. Sanguine but soaked, the athletes dutifully waved and smiled; adorned not in gold, silver or bronze but flimsy ill-fitting plastic ponchos.

Overshadowing this athletes’ parade were the creations of theatre director Thomas Jolly, mastermind of the whole ceremony. Boldly deciding to choose the city as a stage, rather than make use of the conventional choice of a stadium, the sporting side of things was easily forgotten as we witnessed an emphatically kitsch depiction of French history and culture.

Although the weather somewhat thwarted proceedings, it was the content of the performance that drew criticism.

Far-right politicians decried Jolly’s offering as a violation of French nationhood. Conservative pundits focused their criticism on Jolly’s elevation of LGBTQIA+ culture.

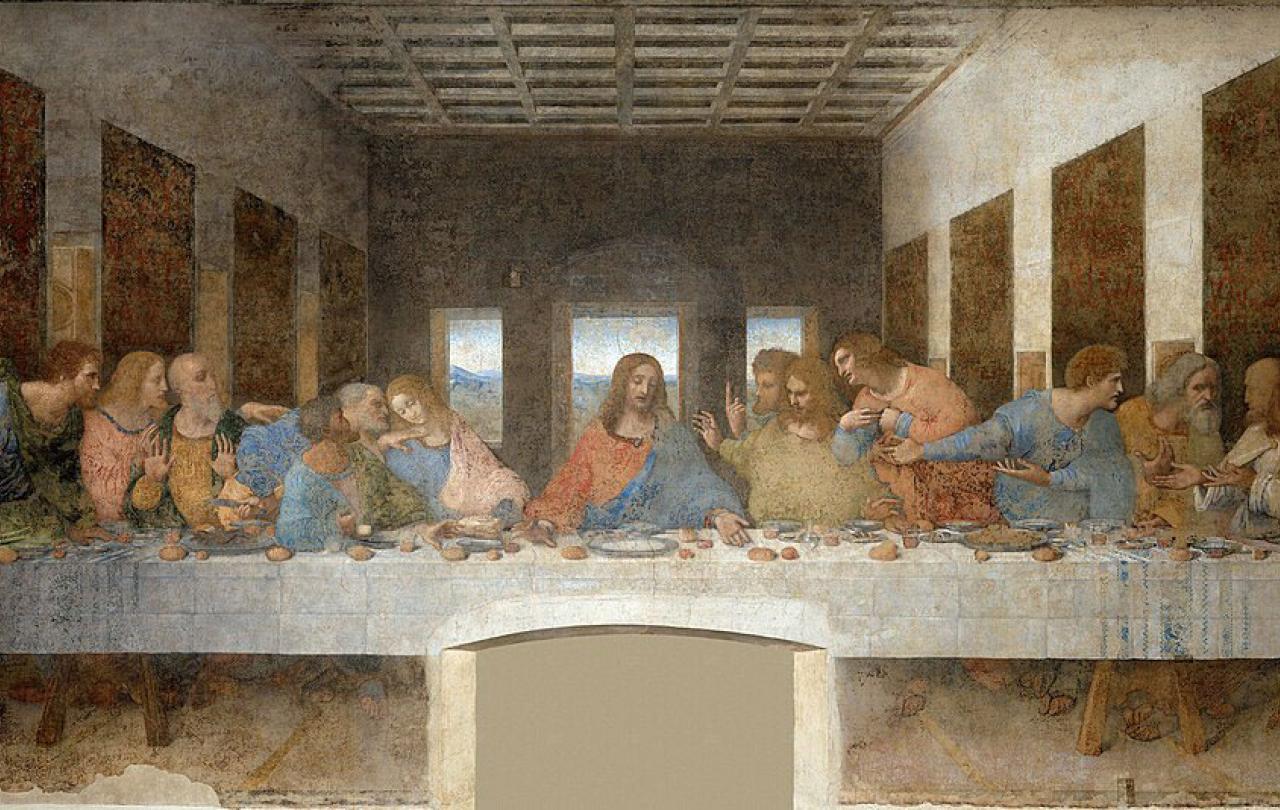

Christian commentators have, with various degrees of rancour, condemned a strange scene where Leonardo da Vinci’s famous painting of the Last Supper was subverted by a pastiche of ostentatiously queer characters. At the centre of which was not Jesus Christ but a robust-looking figure resembling Lady Liberty.

Elon Musk spoke up in protest too, posting that it was ‘extremely disrespectful to Christians.’ Full-throttled cries of blasphemy resound, and probably for good reason. What we witnessed was Christ being usurped and replaced by the insurgency of self-expression and the currently sacred idea of diversity and inclusion.

Ahead of the ceremony, Jolly told British Vogue about the heart behind his creation: “there is room for everyone in Paris. Maybe it’s a little chaotic, it’s true, but that allows everyone to find a place for themselves.” The opening ceremony will be a success, Jolly says, “if everyone feels represented in it.”

I guess this isn’t the case for the thirty per cent of the world who would identify as Christian. That’s because every family and flavour of Christianity would recognise that Holy Communion, the central act of Christian Worship for 2000 years, the institution of which is depicted in da Vinci painting, was being publicly and globally vandalised.

When Christianity becomes moral wallpaper to an entire civilisation and its culture, it unsurprisingly becomes a target for satire.

How can we make sense of this moment? Is there anything more for the Christian to contribute other than indignation or outrage?

Whenever something like this occurs it reminds me of the central role Christianity has played in Western culture. The intelligibility of the ceremony’s controversial scene rests on the idea that da Vinci’s painting is a globally recognised symbol. Otherwise, we would have just been watching a really strange dinner party with no food. But with Da Vinci’s famous painting in our mind the subversive power of Jolly’s scene hits hard.

The view, popularised by the historian Tom Holland among others, would go as far as to suggest that Christianity’s effect on Western culture is so pervasive that even moments of protest and subversion, as we saw in the Paris ceremony, are cultural phenomena inherited from the Protestant Reformation. Regardless of how far you agree with Holland’s thesis, Jolly's subversion only makes sense because of the dominant role Christianity has played in shaping the western imagination, and that is a position of latent power that should cause pause for reflection.

I’ve read half a dozen articles from a certain sort of right-wing journalist who parrot thoughts like, “they wouldn’t do that with the Quran”. That might be right, but it fundamentally misses the point. Blasphemy, let’s say, in Iran, would certainly not involve the Last Supper.

The scene made sense only because of Christianity’s now diminishing position of power but it's a position of power, nonetheless. When you align Jesus Christ with the status quo, with the corridors of power, when Christianity becomes moral wallpaper to an entire civilisation and its culture, it unsurprisingly becomes a target for satire. Especially for anyone or any group that feels persecuted or marginalised. I’m not for a moment defending what Jolly did but trying to understand why it happened.

The last supper, the meal Jesus shared with his friends the night before his crucifixion, was the opening ceremony of Christianity.

The kind of cultural power Christianity has had in the West comes at the cost of clarity because Christianity was itself originally a counterculture. Crucifixion, a supreme act of imperial domination, became the foundation of Christian thought and ultimately its greatest symbol. The original Christian movement was seen itself to be blasphemous for contradictory reasons by both the Jewish and Roman religious leaders of the time.

The fundamental difference between Christianity and merely holding conservative values that should not be transgressed, is God. It was genuine belief in Jesus Christ as the long-awaited messiah of the Jewish people and the Saviour of the whole world - a belief that led his first bedraggled and bewildered disciples to live in such radical and counter-cultural ways that many were killed by the Roman Empire.

It is right for his followers today to speak up and say how wrong it is when the special and sacred things he did for them are yet again trampled on in public, but it's also worth remembering that’s how the story started - with Jesus’ body brutalised and broken. That somehow, in moments like this, we miss the power of Jesus when we simply defend him on grounds of “decency” and “respect.” Instead, if we return to the original events themselves, Jolly’s depiction, in its mockery and subversion, actually reveals the power of The Last Supper.

Da Vinci’s painting was not intended for a gallery but was originally painted on the wall of a fairly obscure monastery, transported to a gallery years later to become primarily art, it is more a foundational aid to the faithful to remember the original events Da Vinci is depicting.

The last supper, the meal Jesus shared with his friends the night before his crucifixion, was the opening ceremony of Christianity. Every time a Christian takes Holy Communion - the central act of Christian worship for over 2,000 years - they remember the opening ceremony where:

“Jesus took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and gave it to his disciples, saying, “Take and eat; this is my body.” Then he took a cup, and when he had given thanks, he gave it to them, saying, “Drink from it, all of you. This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins”

The most peculiar part of the opening ceremony of Christianity - more peculiar than any sight we saw last night - is the presence of Judas. The biblical accounts describe Jesus’ knowledge of Judas’ intentions to betray him to the Romans, and yet Judas is still welcome to the table. If there’s space for Judas, then there is space for all of us. The opening ceremony Christianity cannot be remembered without the presence of Judas the betrayer, and Peter the coward or Thomas the doubter. The great irony and the big mystery of the Christian Faith is that you can’t out-sin grace. You can mock it and subvert it, but Christ died for the ungodly.

Last night’s scene doesn’t come close to the original events. Not only was Jesus betrayed by his friends, he was then tortured, humiliated and executed publicly in just about the most excruciating way humans have devised. That was blasphemy of another level, but it was also victory because God was choosing to love inclusively beyond any human metric.

Tom Holland may be right that no part of western culture has escaped Christian influence, but I want more than a little downstream influence.

This means that there’s nothing more inclusive than the opening ceremony of Christianity and yet, at the same time, nothing more exclusive. It is not us who provide the food but God. In Jolly’s performance, the Last Supper scene was concluded by the French actor Philippe Katerine, emerging painted head to toe in blue. Whilst this bearded smurf caused baffled sniggers across the planet, Katherine was apparently representing Dionysius, The Greek god associated with wild drunken parties. The food on offer by Jolly is wild desire and self-expression. In Christianity the food is God himself, his body and his blood. God’s love is given not simply expressed, even to those who will betray him.

Moments like this will become harder for Christians to navigate. It feels like just as a wave of secular liberalism wants to finally vanquish the power position Christianity has painted for centuries, a new conservative vanguard of resistance is rising to protect or enrol it for its own means. From the mouth of Modi or in Trump’s tirades, a new religiously armed populism is raging. Tom Holland may be right that no part of western culture has escaped Christian influence, but I want more than a little downstream influence.

Take us back to the opening ceremony, to the foundation of Christian faith. Take us to the waterfall, where the torrent flows straight down from the mountain, and save us from the slow-moving sludge of the wide river downstream. Take me back to the opening ceremony of Christianity. To the table where God welcomes a Judas like me, to the meal where the master became a servant and washed his followers' feet. Take me back to eat food I could never afford and wine I could not create.