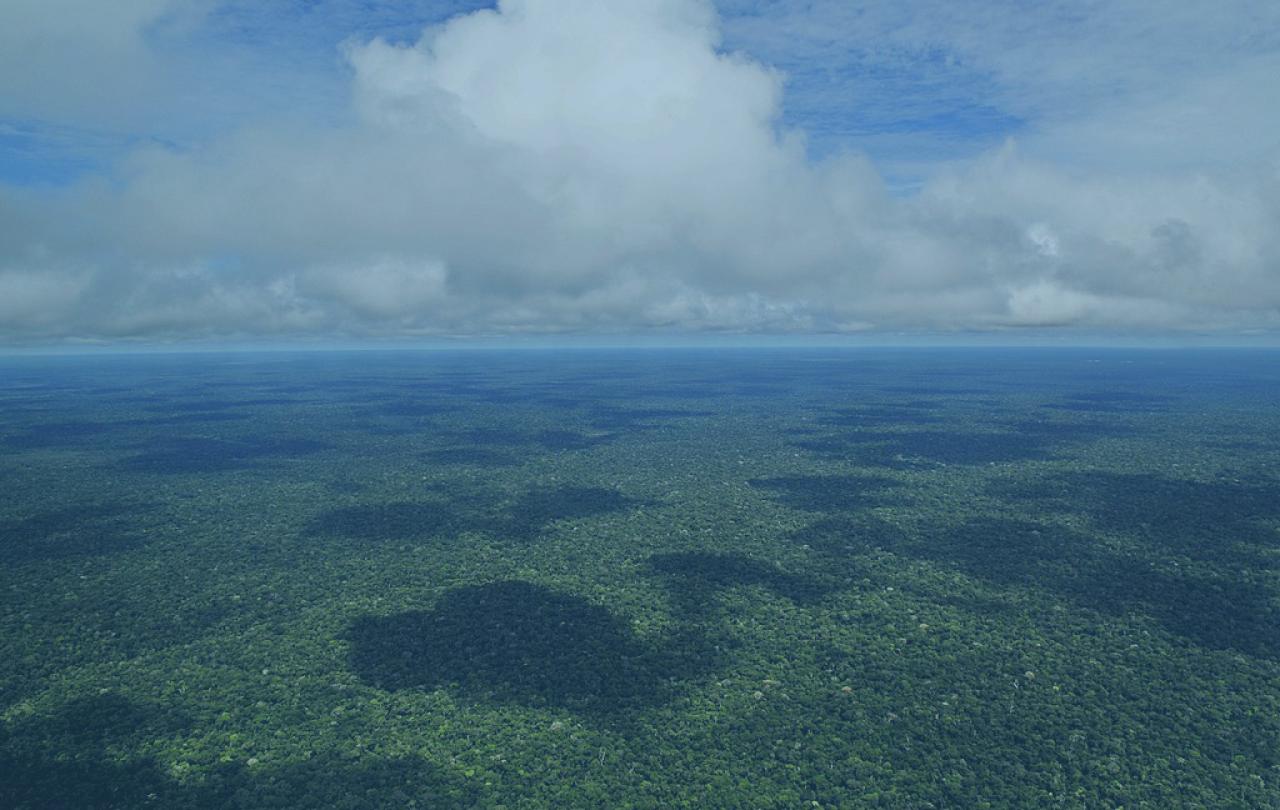

'What drew me back to the Amazon? …it was to savour afresh the unparalleled beauty of this vast region. For me, it is a last frontier, a mysterious universe of its own, where the immense power of nature can be felt as nowhere else on earth.'

These are the words of world renowned Brazilian photographer, Sebastião Salgado, in the foreword of his book, Amazônia. Over a period of six years, Salgado travelled around the Brazilian Amazon photographing its sweeping landscapes: forests, rivers, mountains, as well as the people who live there. A photograph of a Yanomani tribe on the edge of a vast vista with a towering mountain shrouded in cloud in the distance is an extraordinary snapshot of his travels. Salgado documented the daily lives of a dozen indigenous tribes, capturing on camera their warm family bonds, traditional dances and rituals, the artistry of their body painting and means of survival – hunting and fishing. Although Salgado was unable to communicate by speaking to the tribes he visited, he describes vividly how the human emotions he shared with his hosts - to love, laugh, cry and to feel happy or angry – served as their common language. He says:

I felt at home in my own tribe, that of all humans, where myriad systems of logic and reason are interwoven with my own, with those of Homo Sapiens.

During a recent trip to Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, I visited Salgado’s Amazônia exhibition at the Museu do Amanhã (Museum of Tomorrow) in the centre of the city. The photographs are awe inspiring, all in black and white. They depict lush rainforest vegetation, winding rivers and waterfalls. Beautiful people with dark eyes, mainly naked, dressed, feathered and painted according to their tribal traditions sit against a black canvas backdrop or are portrayed in their natural surroundings. Salgado’s talent lies in capturing the epic beauty of the region’s landscapes, but also the delicate detail of the individual faces of the people he photographs. Each person looked straight at the camera lens – and as I looked back at them, it was as if I could see a little of their soul and personality. To the right of each portrait is the name of the person, and a note about their role in the tribe; a reminder that each face is not just a stunning photograph, but a human being who is valued and respected.

But Salgado’s portrayal of the Amazon rainforest, often referred to as “the world’s lung,” is not simply remarkable visual artistry. It is a powerful reminder of a number of issues that we collectively face today as a global tribe of human beings.

For over 10,000 years, humans have enjoyed an inter-connectedness with our natural environment, tending and living off the land. And this is still the case with the Amazonian tribes who rely so tangibly on tapping into the rainforest’s renewable wealth and provision – its animals, fruit, nuts and medicinal plants. A growing body of evidence shows that globally, indigenous people are especially good at sustainably protecting their territories. This is no exception in the Amazon; the indigenous reserves legally ringfenced by the Brazilian government are the areas that are most pristine. The areas where tribes have been driven out have been damaged irretrievably.

With our human quest to develop, the past two hundred years has seen a slow positive global trajectory towards eliminating absolute poverty, reducing conflicts and improving human rights. Encouraging on paper. But this positive change has come at a huge cost to our environment. Ironically, the same expanding global economy which has driven improvements in development and social justice, is based on fossil fuels and high consumption of natural resources causing climate change, mass extinctions and pollution. The results of these changes are hitting the world’s poorest communities the hardest – those who have done the least to cause them. The delicate balance that has existed between humans and our natural environment for millennia is being thrown out of kilter.

COP27, the annual UN global climate conference took place in Egypt at the end of 2022 and the impact of the climate crisis on vulnerable countries was finally on the agenda. It is promising to see growing public support from across the world for action. More people than ever before – including Christians and churches – are speaking up for climate justice, campaigning, joining marches and praying for change. Christian NGOs and pressure groups, such as Tearfund, Christian Action, and World Vision to name a few, are often at the forefront of climate campaigns.

So why are Christians calling for climate action? First, it’s an issue of ownership. As campaigner Ruth Valerio explains: the Bible tells them that creation was made by Jesus, through Jesus and for Jesus. Therefore, this world that was made brimming with abundance and vitality has immense value to God. The world is not ours to do with as we please, it belongs to its creator who has entrusted it to humans to care for. Second, it’s an issue of justice. The outworking of climate breakdown, such as global temperatures rising, floods, drought and extreme weather events has a disproportionate impact on people in poverty and who are already vulnerable, affecting their livelihoods, health and security. Christians believe that we’re all made ’in the image of God’. This speaks powerfully of equality between each one of us within our global human tribe.

Therefore acting justly means responding to the needs of our global neighbours, not only our immediate communities. The Bible says ‘Speak up and judge fairly; defend the rights of the poor and needy’. Christians – especially those living in privileged countries with social safety nets and funds to invest in climate resilience – are asked to stand up for equality and justice, calling on those in positions of power to make decisions that protect those who are more vulnerable, as well as this Earth that belongs to God.

At COP27 these Christian groups joined with countries vulnerable to the impacts of climate change to call for justice in climate financing. It’s a simple but radical case of compensation; rich nations who have already used far more than their fair share of carbon to develop their economies should now pay for the unavoidable “loss and damage” experienced by those whose homes, livelihoods and even lives are being lost as a result of the climate crisis. The protection of the Amazon also remains a critical theme.

Addressing the COP27 conference, Brazilian President Elect Lula said,

There is no climate security for the world without a protected Amazon.

Visiting the Amazon rainforest with my family in 2019 I was stunned, like Salgado, by its majesty and magnitude. Sleek, dark waters teeming with fish and crocodiles, trees with trunks that curved and curled, and the cacophony of sounds and song – amphibians, birds and beasts - that accompanied the sudden blackness of the night that fell like a curtain. This is creation as God meant it to be – in all its life and vitality. Can our vast human tribe, scattered and concentrated across the earth, who all laugh and cry and love under this single sky, unite and make the critical decisions needed to care for each other and our world? The protection of Amazonia is only one part of the solution, but it’s an integral part. So will we act? Before it’s too late and Salgado’s extraordinary photographs become simply a segment of history showing future generations the way it used to be?