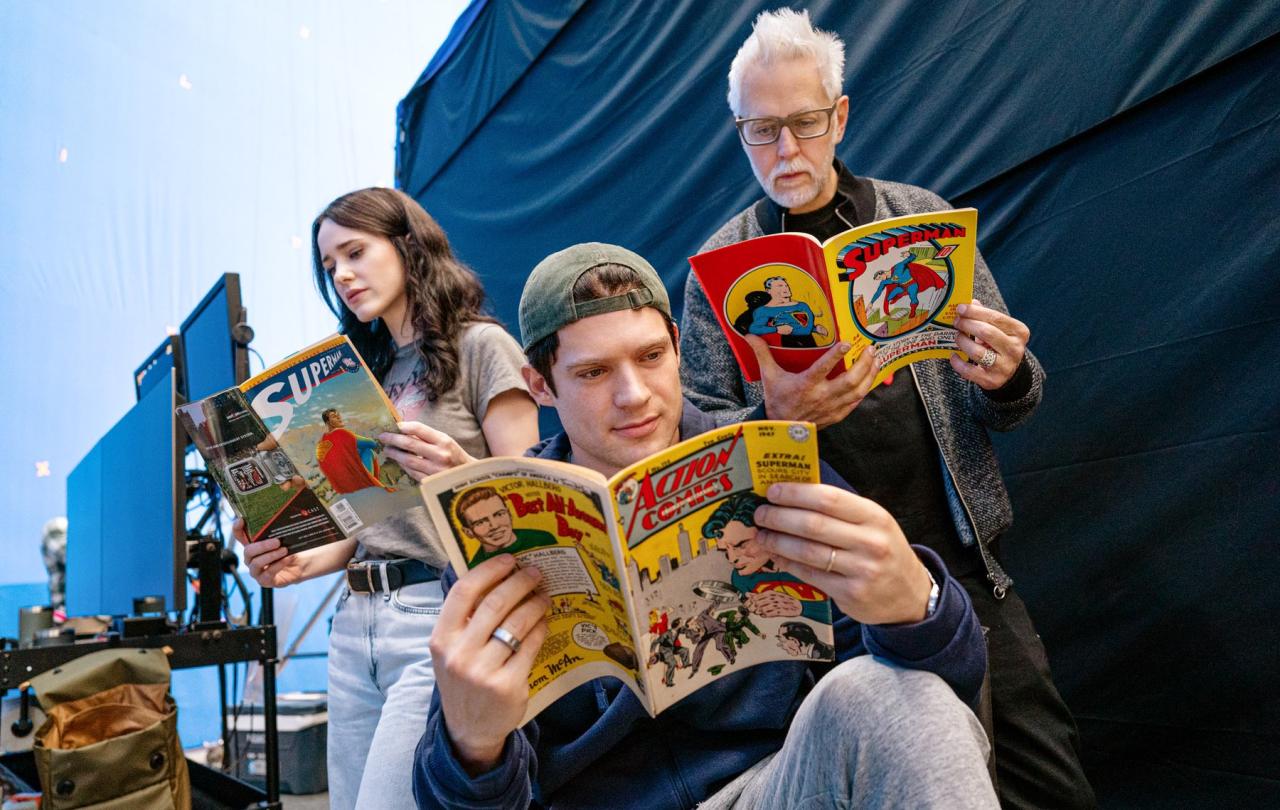

This month is sure to leave cinemagoers vibrating with excitement as we see the long-awaited release of James Gunn’s Superman film, starring David Corenswet as the titular last son of Krypton and Rachel Brosnahan as Lois Lane.

If the trailer is anything to go by, the film is going to be leaning into some of the more whimsical aspects of the character, which may well be a reaction against the darker, grittier interpretation we saw in Zack Snyder’s Man of Steel, Batman vs. Superman and Justice League films. Snyder was depicting a Superman with genuine pathos, one that emphasised the messiah parallels of a man with god-like abilities. Snyder may have leaned into the ‘Superman-as-God’ angle, but he didn’t invent that perspective. In fact, it’s an aspect that may well have been there from the very beginning.

So, before we watch the new film and once again believe a man can fly, let’s dive into his background and see how much messiah there is in the Man of Steel.

The first thing that we’re going to focus on is the idea of Superman as a Jewish superhero. I would love to say that I was the first person to spot this, but I am at best, the 6,289th person to spot this particular parallel. But it’s definitely not talked about enough. Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were both Jewish European immigrants. Like Stan Lee at Marvel some twenty years later, they probably understood the feeling of looking the same, but being treated differently by people. Similarly, Kal-El looks just like a normal human man, but is anything but. There is a reason that the comic book industry at this time appears to have so many Jewish creatives in it, and that’s because the anti-Semitism of mid-twentieth century America created a strong barrier to getting any more prestigious jobs. You need to remember that at this point comic books and comic book creators were not considered special or valuable in any way. These days, a person would need to be exceptionally talented and phenomenally well connected to get a foot in the door at DC or Marvel. Whereas at that time, a high school education and the ability to write or draw were enough to get you a decent spot. Jewish people were not able to get jobs in advertising or publishing, and no one was really bragging about their work in comics. Comics back then were treated like they were disposable, like collecting newspapers. That’s why getting hold of a copy of something like Action Comics #1 or Detective Comics #27 (the first appearances of Superman and Batman respectively) is so rare. It would just not occur to anyone to keep a copy.

But the more we look at Superman, the more Jewish parallels we see. Let’s look at Moses, one of the most central figures in Judaism, who is also a key figure in Christianity.

Many of you will be familiar with Moses’s ‘origin story’. At the time of the story, the Hebrews are enslaved in Egypt, and the Pharaoh was controlling the population by killing every Hebrew baby boy at birth. So, the mother of one boy places her baby in a basket and hides him in the reeds along the banks of the Nile. The boy’s older sister watches over him from a distance. The basket is spotted by the daughter of the Pharaoh as she is going down to bathe. She speaks to the baby’s older sister, who cunningly offers the baby’s own mother as a wet nurse without revealing her parental connection. The Pharaoh’s daughter agrees and decides to raise him as her own son.

So what we have here is a baby being sent away by their parents from what would almost certainly be total destruction, and death. The baby is found by a prospective parent who then adopts them as their own. That baby then grows up to be the child of two worlds, at some points torn between a dual heritage, but nonetheless able to go on to achieve miraculous things. We are literally one spaceship away from Superman’s origin story.

Next, let’s consider Superman’s real name. No, not ‘Clark Kent’, I mean his real name; Kal-El. This made-up name sounds similar to some words in Hebrew. For example, the suffix El, means ‘of God’. This has led to some scholars interpreting the name Kal-El as ‘Voice of God’. ‘Clark Kent’ was said to be inspired by explorer William Clark, who along with Meriwether Lewis (‘Lois and Clark’, get it?) were the American explorers who discovered an overland route to the Pacific Ocean. Therefore as well as ‘Superman’, he has one name with significance in Hebrew, and another anglicised name that was a nod to American history. The idea that Superman has a real name and a public name is another Jewish element. At the time many Jewish people knew that they could be identified, and therefore persecuted, for their name. In Hollywood, ‘Bernard Schwartz’ became ‘Tony Curtis’, ‘Issur Danielovitch Demsky’ became ‘Kirk Douglas’. Even over at Marvel, ‘Stanley Martin Lieber’ became ‘Stan Lee’ (nice one Stan). This is a practise that continues to this day. You may not know the name ‘Natalie Herschlag’, but suffice to say she absolutely killed it as the Mighty Thor.

It is easy to read Superman as an immigrant’s desire to belong to their adopted society and make a positive contribution to it.

Some of the conscious influences for Superman came from characters like Zorro, or the Scarlet Pimpernel, and was said to be visually inspired by Douglas Fairbanks. But what is interesting is if we think about what things could have unconsciously inspired the creation of Superman. The term ‘Superman’ was used fairly commonly in the twenties and thirties to refer to men doing phenomenal feats. However, if we hearken all the way back to Friedrich Nietzsche’s first reference to the Ubermensche, this has sometimes been translated (quite poorly) into ‘Superman.’ Now, both Siegel and Shuster have denied that Nietzsche was an influence in the creation of Superman, but considering that the ubermensche was such a popular idea in 1930s Nazi Germany at the time, it’s fun to see Superman as a reaction against this. If you imagine that the strongest most powerful man alive is also Jewish, then I imagine Jewish readers might get a kick out of that.

As Christianity sprang from Judaism, there’s not always a clear delineation in terms of who is important to which religion. Since we’ve covered Moses, we need to look at another Jewish man who caused quite a stir; Jesus. It is not difficult to see the parallels between ‘the last son of Krypton’ and ‘the Son of Man’. Kal-El is sent to earth from another world by his father, to save the human race.

This parallel is particularly explicit in Russell Crowe’s incarnation of Jor-El in 2013’s Man of Steel when he says:

‘You will give the people of Earth an ideal to strive towards. They will race behind you, they will stumble, they will fall. But in time, they will join you in the sun, Kal. In time, you will help them accomplish wonders’.

Superman and Jesus are both raised in a humble setting (Clark is raised on a farm and Jesus is raised to be a tektōn, which is often interpreted as a ‘carpenter’ but could just as easily be ‘builder’). Neither Nazareth, nor Kansas were thought to be particularly glamorous places (sorry Kansas!) and yet, both grow up to become the saviour of the world. Superman spends time in his ‘Fortress of Solitude’ to learn from his father, Jesus spends time praying and fasting in the wilderness. Same principle, but very different aesthetic.

Jesus may have been the messiah, but he was not the kind of messiah high on first century Jewish people’s wish-list. Having been oppressed by the Romans for over 90 years at the time of Jesus’ ministry, the Jewish people were desperate for a messiah and to put it delicately, Jesus was not what most Jewish people were expecting. They expected a warrior, a champion who would throw off the oppressors of the Jewish people.

So it’s possible to consider that Siegel and Shuster are, in fact, creating the Jewish messiah. Superman uses force, his unrivalled physical strength and power, to protect people. When you consider the first Superman comic came out just before the start of the second world war, it adds real weight to this desire for a mighty protector. In fact, Superman is also compared to Samson, an Old Testament figure who is granted supernatural strength; and this is what the Jewish people were expecting from a messiah. Jesus is not this. He didn’t fight, he didn’t raise rebellions, he didn’t incite violence against the oppressors. His fight was in the form of the ultimate sacrifice. Any hero who dies to save his friends is an automatic Christ parallel right there, and Superman has died more than his fair share.

When all is said and done, it’s Superman’s unwavering morality, not his physical strength and power, that makes him most like Jesus. Superman is incredibly gentle and peaceful. He doesn’t want to dominate and he tries to avoid violence on the whole. It would take far too long to determine exactly what came from Siegel and Schuster and what has been added in the subsequent decades by other writers. But it is easy to read Superman as an immigrant’s desire to belong to their adopted society and make a positive contribution to it. Along with Batman, Spiderman and Wonder Woman, Superman transcends the comic book universe that he belongs to. He exists in the hearts and minds of every person who once loved him in any iteration, and it’s possible that his influence from the meta-narratives in Judaism and Christianity helped him to be embraced by society at large. Or it could just be the cape and the tights, who knows?

Support Seen & Unseen

Since Spring 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,500 articles. All for free.

This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief