Nuclear War A Scenario (Torva, 2024) by Annie Jacobsen is about the most depressing book you could ever read and, perversely, all the more reason to read it. Collectively, the human race has buried its head in the sand over the existence, power and proliferation of nuclear weapons. We are understandably focussed on the lasting impacts of climate change; however, nuclear war promises planetary destruction and the risks surrounding it have grown, rather than lessened, since the end of the Cold War.

To help us focus on what we would rather not, Annie Jacobsen gives her book a plausible but hypothetical scenario. It starts with North Korea, for there we have an unbalanced, remote individual; an empathy free despot with unfettered power and unimaginable weapons at his disposal that now have the capacity to reach the east coast of the United States.

We do not learn his reasons for launching missiles against the US in the scenario and never would, were it to happen, because Armageddon takes only minutes to unfold. Jacobsen is deeply informed round nuclear war, having talked to many highly placed American officials. One recurring anxiety she meets is that the decision to launch nuclear missiles is in the hands of the President alone and the US still operates on the so-called Launch on Warning doctrine.

Launch on Warning means America will fire its nuclear weapons once its early warning sensor systems merely warn of an impending nuclear attack. These systems are sophisticated, but they can also be wrong, as the US discovered in 1979 when it briefly believed it was under attack from the Soviet Union. In Jacobsen’s scenario, the President has six minutes to decide what measures to take and has something approximating a menu to assist with this. Ronald Reagan observed:

Six minutes to decide how to respond to a blip on a radar scope and decide whether to release Armageddon! How could anyone apply reason at a time like that?

The menu, a little like ordering pizza with preferred toppings, is supposed to help with that moment.

In Jacobsen’s scenario, US nuclear weapons are unleashed against North Korea but have to travel over Russia to get there. Russia’s early warning systems are less sophisticated and in the scenario these US missiles are believed to be an attack on Russia, not North Korea. This leads to Russia’s own uncompromising, near instantaneous response which leads to … well, you get the picture.

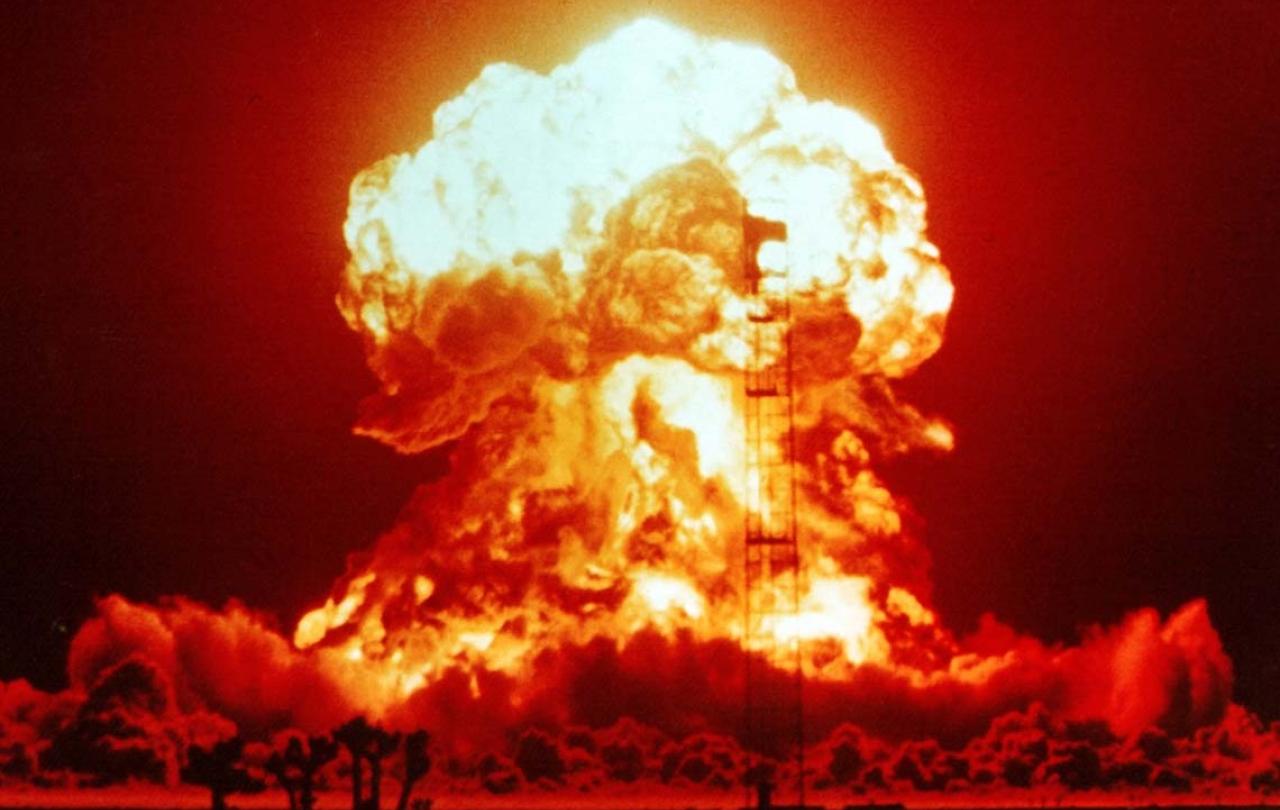

A one megaton thermonuclear weapon detonates at one hundred and eighty million degrees Fahrenheit, which is four or five times hotter than the temperature at the centre of the sun and creates a fireball that expands at millions of miles an hour. This alone is unimaginable; replicating it hundreds of times over is impossible. The injuries sustained among those left; the loss of food, water, sanitation; the breakdown of law and order; the arrival of nuclear winter where temperatures plummet for decades without any infrastructure led Nikita Khrushchev to say: ‘the survivors will envy the dead’.

Mark Lynas, a writer who for years has been helping the world to understand the science of climate change has recently turned his focus on the nuclear threat in his book ‘Six Minutes to Winter’. He observes:

‘There’s no adaptation options for nuclear war. Nuclear winter will kill virtually the entire human population. And there’s nothing you can do to prepare, and there’s nothing you can do to adapt when it happens, because it happens over the space of hours. It is a vastly more catastrophic, existential risk than climate change.’

Reaching the end of human capacity is an unsettling experience. Solutionism is the Valley’s mantra: technology can solve every human problem, but binary thinking neglects the social, political and moral complexity of many issues and, in any case, catastrophic nuclear explosions are as likely to happen by accident as design - and could do at any time. It’s not that we need more time for AI to resolve this existential threat; it’s that it never will.

This is where the moral strength of faith traditions come into play as people embrace the strange hope of the powerless. Christian faith in particular cannot succumb to fatalism or the hacking of the book of Revelation to interpret the end of all things as code for nuclear war. God is creator and we are co-creators with him; we are not called to destruction when he has promised to renew the face of the earth through the resurrection of Christ.

There is something specific about our generation. For eighty years, since the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, we have been the first generation with the capacity to destroy the whole world. Understandably, we do not want to think about this, but the fallout from this nuclear denial is that risks continue to multiply. More nations are thinking about developing nuclear weapons in an unstable world. In June 2025, the global nuclear watchdog, the IAEA said Iran was failing to meet its non-proliferation obligations for the first time in two decades and within days, Israel had launched missile strikes on Iranian nuclear sites – and many other targets – to set its nuclear programme back, followed in a significant escalation by US strikes. Nuclear weapons are a very present cause of insecurity, as the recent missile exchanges between India and Pakistan show so gravely.

Despots watched what happened to Muammar Gaddafi after he relinquished his designs on weapons of mass destruction following pressure from western powers and are unlikely to make the same mistake. No-one can be sure the current US administration will offer a nuclear umbrella to Europe, especially when the President’s instincts are not internationalist and his preoccupation is with a golden dome shielding continental America instead.

Almost no-one has agency in this, except for one vital piece of the puzzle: intercessory prayer, rooted in the promises of God. The ancient psalm writer prophesies:

He makes wars cease to the end of the earth;

He breaks the bow and shatters the spear;

He burns the shields with fire.

Be still, and know that I am God!

I am exalted among the nations,

I am exalted in the earth.

And something greater than the spear is among us today.

Support Seen & Unseen

Since Spring 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,500 articles. All for free.

This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief