But it can be found in politics. Baroness Cathy Ashton, whose many achievements include brokering an agreement between Serbia and Kosovo and negotiating the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action with Iran, has written a memoir.

She was a guest on The Rest is Politics, the podcast hosted by Alastair Campbell and Rory Stewart, of both of whom a neuro-surgeon might observe that humility bypasses have been a complete success. But she is a perfect exemplar of what Stewart called, towards the end of the interview, “radical humility”.

This, Stewart observed, counters the “Great Man” theory of history, the super-hero who saves his people – the character currently channelled by so many populist leaders, with Donald Trump as its apotheosis.

Ashton herself said things like “we do our best”, that there’s a web of small, interconnected acts that reach a successful resolution and that the deals aren’t hers to make, but belong to the people making them. A lesson that could be taken from Kosovo to complex circumstances such as British transport infrastructure, the nature of our union, or local governance from Birmingham to Newcastle.

This is radical humility, a Cinderella quality to its ugly sister “radical honesty”, the latter developed since the Nineties by the American psychotherapist Brad Blanton, which is really a licence for being rude. Radical humility, by contrast, puts its practitioner firmly at the service of those affected by a political situation and enables them to resolve it.

Impressed as he was by the concept, Campbell neatly summarised the problem of deploying it as a political slogan: “What do we want? Radical humility! When do we want it? Now!”

But radical humility should be a given for the way we manage the administrative organs of our faith, the Churches. Cardinal Basil Hume, the Archbishop of Westminster who never forgot he was foremost a Benedictine monk, springs to mind.

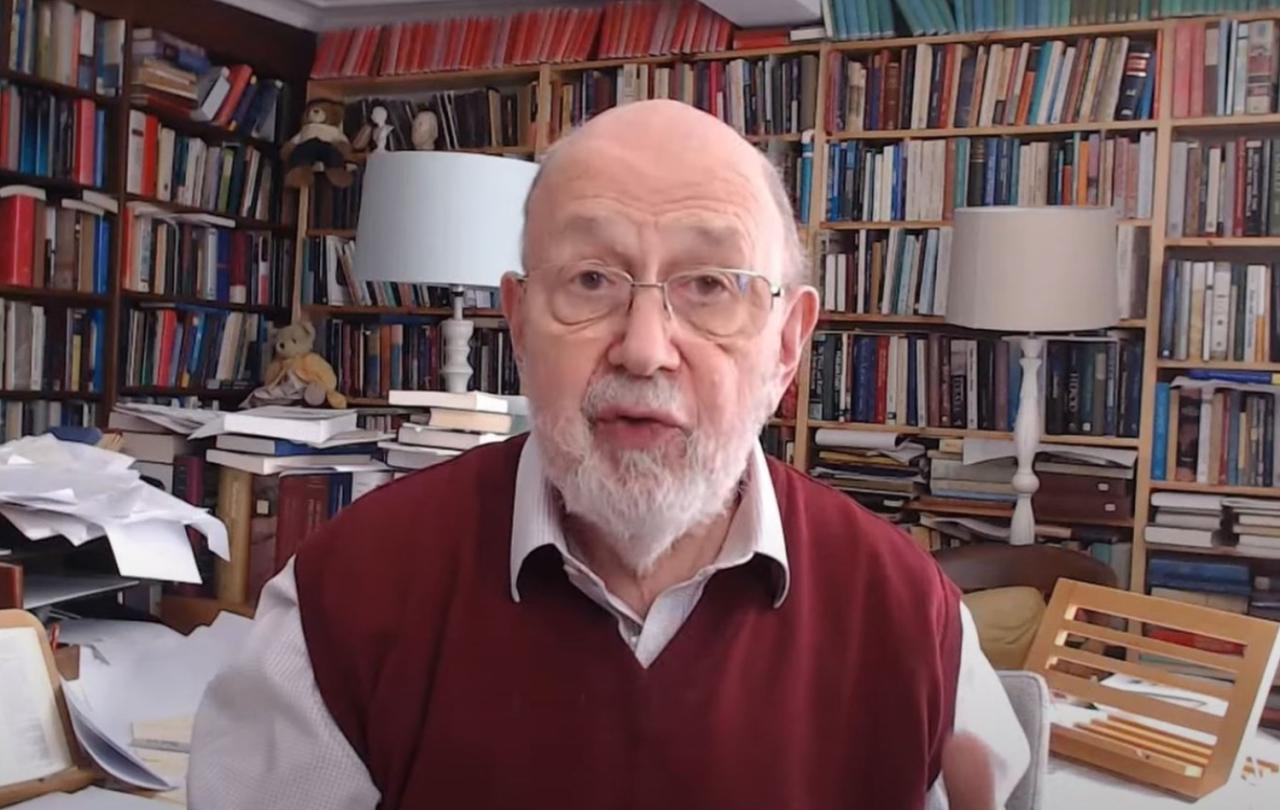

As does Rowan Williams, whom I observed from the Daily Telegraph and then as his principal spin-doctor between 2008 and 2011, holding the complexity of the Anglican Communion together by empowering its components.