There’s hardly been a livelier time for evolutionary science than today; indeed, passions can run high. It’s not that Darwin’s vision of evolution is fundamentally in doubt: species adapt by natural selection, there’s variation between individuals, and those better adapted for their environment survive more often, passing on their genes to their children. In that, the theory of evolution stands, but many other parts of the evolutionary picture from the second half of the twentieth century are coming under criticism. That includes the following maxims:

‘the only significant form of inheritance involves genetic code’,

‘nothing that happens to an organism during its lifetime is passed on to its progeny’,

‘we agree what we mean by “species”’,

‘genes pass down the branches of the tree of life, not between them’,

and ‘evolution is fundamentally all about competition, not cooperation’.

Among the excellent crop of writers on these themes, Eva Jablonka and Marion Lamb stand out for their elegant prose, and a gift for communicating complex ideas clearly. As they recognise, the standard mid-twentieth century model of evolution might be worth criticising, but it’s also landed all sorts of important basic points. (They list ten.) The shortfall of the earlier, dominant theory was in being too narrow, with each insight too quickly eclipsing others.

Here are two examples. First, the classic twentieth century picture saw inheritance in terms of DNA and genes, passed on by ‘germline’ cells, such sperm and pollen. That’s all true, but it shouldn’t restrict our wider view of inheritance to that. Today, writers such as Jablonka and Lamb stress that organisms inherit from their parents (or parent) in all sorts of ways.

A second plank of the twentieth century picture is that evolution involves descent from a common ancestor. Again, that says something vital, even central, accepted by evolutionist old and new. The twentieth century position, however, added a restriction: that’s all that’s important on this score. The newer perspective recognises that while genes are – of course – central, and passed on from parent to child, organisms also swap genes between themselves (between branches of the tree of life, not just along those branches), even between very different species.

If we’re not careful, what’s written and taught (not least by theologians), even with the best will in the world, will be thirty or even fifty years out of date.

There’s a lot of excitement around these sorts of claims (and, remember, Jablonka and Lamb make eight more), and that can get quite noisy. Defenders of the older, narrower picture typically say that the newer themes are simply fuss over minor points. Advocates of the newer perspective disagree, saying that the twentieth century picture risks missing some important features of biology, which are now coming into better focus.

Why such debates matters

Why might this ferment among biologists matter for a site like this one, and for theologians, and discussions of religious matters? Well, for one thing, as I pointed out in my previous article, nothing quite dissolves the supposed animosity between science and religion (which is, after all, a relatively recent invention) like theologians and religious people getting excited about biology. It’s also important that any humanities scholar, the theologian among them, who’s engaging with science should keep up to date. If we’re not careful, what’s written and taught (not least by theologians), even with the best will in the world, will be thirty or even fifty years out of date.

But there’s more at stake. As we have seen, the twentieth century picture, for all it brought an admirable clarity to evolutionary thought, was reductionistic. We see that in Jablonka and Lamb’s exhortation to scientists: ‘yes, stress x, but don’t think that means you have to deny y.’ A religious vision tends to be an expansive one. It wants to recognise the reality and value of all sorts of things. Yes, there’s matter, atoms, molecules, and genes, but there’s also organisms, agents, cultures, groups, economies, hopes, loves. They’re all real. We can’t reduce one to the other: not organisms to genes, or agents to economies. A turn from reduction is welcome.

More than that, almost everything in the emerging twenty-first century view of evolution is fascinating from a theological perspective.

Take convergence, for instance. It turns out that evolution isn’t just driven by randomness, or by the demands of the surroundings. Also important are various features of physics, or mathematics – the contours of reality – that throw up elegant solutions to evolutionary problems, which are adopted by evolution time and again. Wherever you need to sturdy and space-efficient packing of cells (as in a honey comb, or a a wasp’s nest), the hexagon is ready and waiting. Wherever there’s water or air to navigate, the laws of fluid dynamics are bound to throw up wings, and bodies shaped like fish, dolphins, and penguins (which are all quite similar in shape).

How do we know this? Because evolution has converged on wings and that body shape independently, many times, as also on eyes, and everything else that Simon Conway Morris lists in the nine closely printed columns of convergences in the index to his book Life’s Solution. Evolution certainly involves randomness and need, but alongside them is something more like Plato’s forms: timeless realities, there to be discovered and put to work. Among the more theological of these eternal verities, covered in Conway Morris’s book, are perception, intelligence, community, communication, cooperation, altruism, farming, or construction

Exceeding a zero-sum game

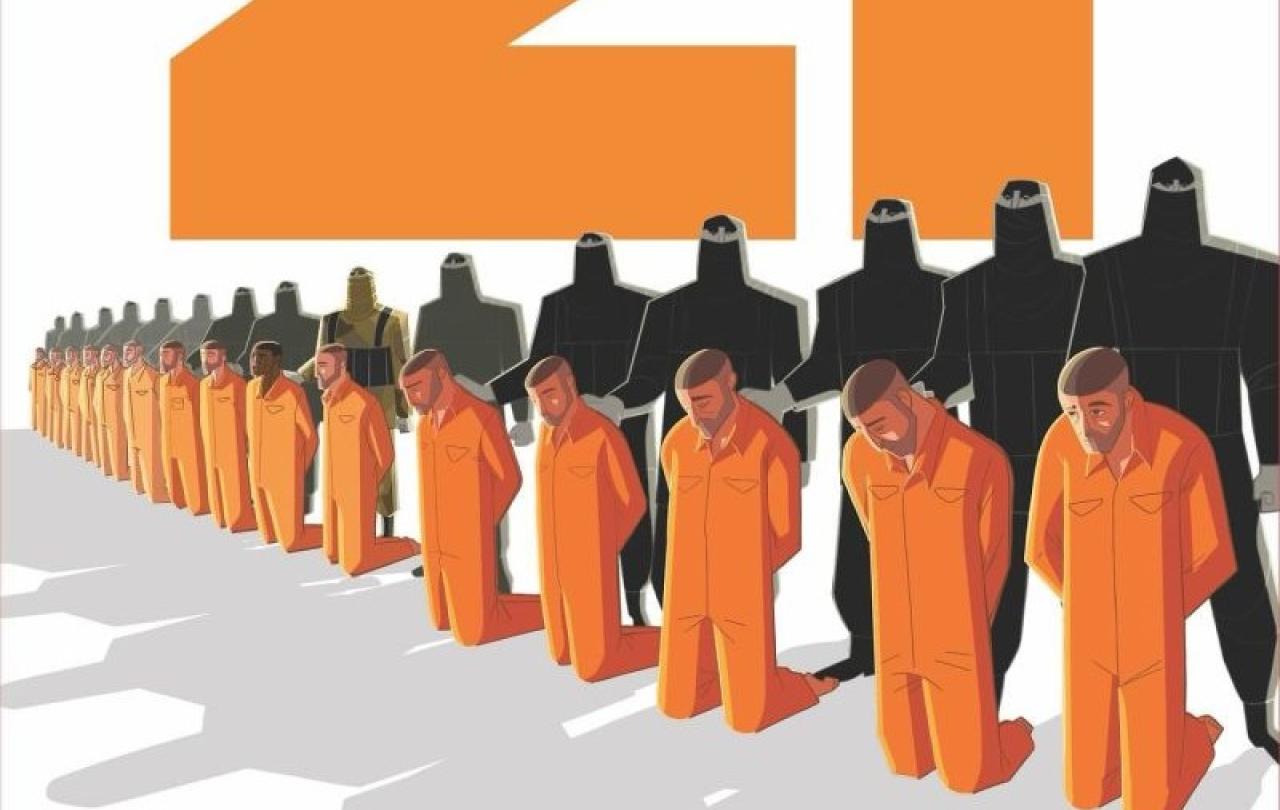

Then there’s cooperation. Ever since Darwin’s Origin was published, and, even more, ever since Tennyson wrote about nature ‘red in tooth and claw’, theologians have been embarrassed about the place of cooperation in their vision of the world. Now, however, it turns out, competition isn’t the only force at work in biology or evolution after all. One of the features of reality that evolution discovers and puts to work again and again is cooperation, and ways to exceed a ‘zero-sum’ game. We see that in cooperation within a species, but also in cooperation between species, which is ubiquitous in nature: called mutualism, it’s found everywhere. As a rule, once two species stick around in proximity for the long run, down many generations, their relationship will turn to mutual benefit.

Ethicists are often wary of the suggestion that we can look at the way things are, and read a moral code there (getting an ‘ought’ from an ‘is’), but it’s an unusual person whose vision of right and wrong isn’t shaped, to some degree, by a sense of what the world is like. Well, it turns out that nature bears witness to the enduring worth of cooperation, and not only to competition.

In the first of these articles on biology, I pointed out the significance of ethics in thinking about biology, and about evolution in particular. For better or worse, and often for worse, thinking about evolution has been an ethical, social, political story. The evolutionary has been put to work for immoral, ends. It turns out to be wrong twice over to suppose evolution commends only competition. It’s wrong, first of all, because we are rational creatures, who can aspire to an understanding of good and evil that transcends the realm of nature. But also, as we now see, it’s wrong even to suppose the nature is only red in tooth and claw. There’s competition, but there’s also a lot of cooperation.

Suggested further reading

Archibald, John. 2014. One Plus One Equals One: Symbiosis and the Evolution of Complex Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. An accessible introduction to biological mutualism, with an emphasis on the role of hybrid organisms (one living inside another) in major evolutionary transitions.

Bronstein, Judith L., ed. 2015. Mutualism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. The new standard treatment of biological mutualism.

Morris, Simon Conway. 2008. Life’s Solution: Inevitable Humans in a Lonely Universe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. A comprehensive discussion of convergence in evolution.

Day, Troy, and Russell Bonduriansky. 2018. Extended Heredity: A New Understanding of Inheritance and Evolution. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. An engaging introduction to a broadened picture of inheritance.

Davison, Andrew. 2020a. Biological Mutualism: A Scientific Survey. Theology and Science 18 (2): 190–210. An accessible survey of some of the science of biological mutualism.

———. 2020b. Christian Doctrine and Biological Mutualism: Some Explorations in Systematic and Philosophical Theology. Theology and Science 18 (2): 258–78. A foray into some of the significance of mutualism for Christian theology.

Jablonka, Eva, and Marion Lamb. 2020. Inheritance Systems and the Extended Synthesis. Cambridge University Press. A short discussion of many of the more expansive aspects proposed for contemporary evolutionary thought.

Jablonka, Eva, Marion J. Lamb, and Anna Zeligowski. 2014. Evolution in Four Dimensions: Genetic, Epigenetic, Behavioral, and Symbolic Variation in the History of Life. Revised edition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. One of the most substantial discussions of the new perspective.

Laland, Kevin, Tobias Uller, arc Feldman, Kim Sterelny, Gerd B. Müller, Armin Moczek, Eva Jablonka, et al. 2014. Does Evolutionary Theory Need a Rethink? Nature 514 (7521): 161–64. MA short two-sided piece, asking whether a transformation in evolutionary thinking is under way.