Every day he wakes up, he feels something is wrong.

Is it this place? Or is it him?

He cannot say. Only that this sensation of wrongness feels a lot like… fear. Like a kind of haunting.

Who am I?

Memories with the answer to this question visit his mind like ghosts in the night, but by morning time - if you can call it morning - they have slipped away. Instead the Voice answers for him.

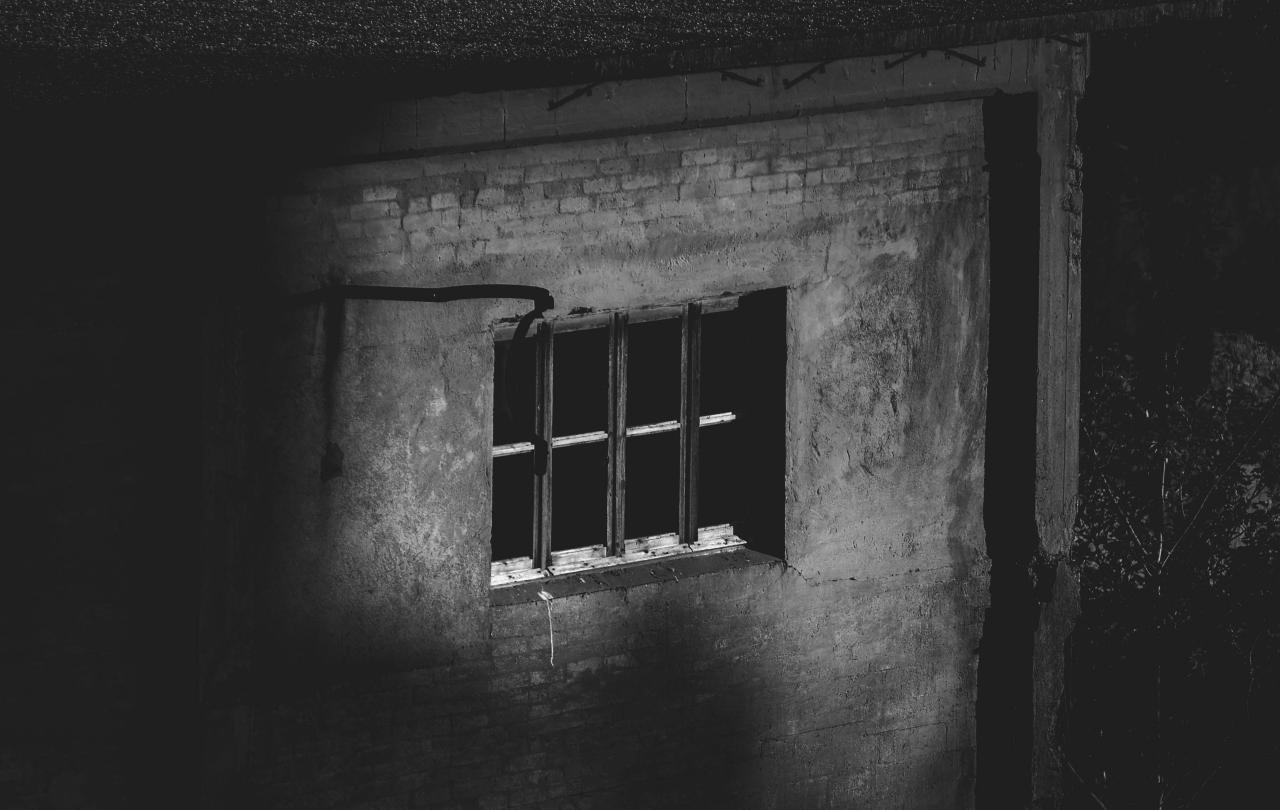

He calls it morning, but it is only the time when he wakes. The light around him changes little with the passing of time. Always he is cocooned in a soupy gloom. The air is stale and still, a little damp, and yet a trace of sweetness is mixed in with the miasma which has, at times, persuaded him this is comfortable, even pleasant. At least tolerable. The walls around him are the only constant. No, there is also a door - he has seen its hinges but he knows it is locked fast because the Voice has told him so. Apart from these, there is little else to look upon except what the Voice sometimes shows him through an opening which it calls the Window. It opens only when there is something to see, otherwise it too is shut fast.

The chains of course are another constant, he remembers. He feels their weight when he moves about. And for this reason, he doesn’t trouble himself to move far. Some days, not at all. They make him feel weary almost before he has begun. It is useless anyway; the Voice has told him. It is his lot to exist in this place, so he can only make the best of it for whatever time he has left. It is the lot of the Voice to look after him.

He lifts his head, sniffs the stale air, scratches at an ear.

At once, the Voice sounds from its aperture high on the cell wall. ’Good morning, Rat! How are we today?’

‘Same,’ he mumbles into his paws.

‘Why, that is excellent! The same is good. The same is the best one can ever expect. The same is life.’

‘So you have told me.’

‘Because it is the truth. And however ugly or grim, the truth is never to be shunned. Have I not always told you this?’

For a longish moment, the Rat does not answer.

‘I said: have I not always told you this?’

‘You have,’ the Rat murmurs.

‘Honestly, sometimes I wonder whether you actually listen to all that I have to say. Else I wouldn’t have to repeat myself. But at least one of us must do their duty. So, to be sure, Rat, I had better remind you once more, just as I do with all those under my care.’

The Voice begins to speak in that quick, forceful manner the Rat has come to accept. As if nothing it says is above the mundane and therefore worth dwelling upon, and yet all is also irrefutably and obviously true.

The Rat knows the litany well.

First, and above all, he is a rat. And as a rat, he belongs in this dank, dark place. It is where rats of his kind have always dwelled. Everyone knows rats carry disease. Everyone knows rats have no useful value. No purpose, no meaning, and therefore they should have no voice, above a nasty little squeaking, because after all, no one wants to hear what a rat has to say. The Maker has ordered it so.

‘Thus is the verdict,’ the Voice concludes. ‘And yet, in his mercy, the Maker tolerates your continued existence. That is why he created this place and appointed me guardian over you. To care for you, even though it is more than you deserve. To feed you enough to keep your belly full, even though such provision comes at great expense. And to keep you entertained, even though, Maker knows, such effort is a downright extravagance.’

The Voice comes to the end of its discourse. And as always, the moment it is finished, a small shutter opens in the most foetid corner of the place and a platter of food is shoved through. The shutter closes at once with a snap.

Bracing himself to the weight of his chains, the Rat crawls over to the platter and has a sniff. It is the same as every day. A bolus of food which in the dim shadows forms no distinct shape or colour. Its texture is neither hard nor soft. It gives off no smell that could appeal or repel. He eats it down, as he does every day. The first taste of it upon his tongue is sweet - the promise of something good. But by the time he swallows it down, the sweetness is gone and what remains is a solid feeling in his belly, at once heavy and bitter. The Voice has told him this is Nourishment. This keeps him alive - which is his only principle, his only goal. And so he knows tomorrow he will eat again.

The platter lies empty for a while; it will be taken when he sleeps. Next will come the Window. Each day he has not long to wait. The Voice tells him this is so that his mind is not inert. ‘For an empty mind is a dangerous thing,’ the Voice has said, ‘into which all kind of falsities are wont to slip. It is for me to protect you from such hazards. By filling it.’

The Rat moves over towards the Window. He cannot see the Window; he cannot see very much at all. But by instinct now, he knows where it will appear. He almost knows what it will show. Each day is different - yes, the only difference in his drab world - but there is a kind of regularity to what it shows, too. And in any case, it leaves him with the same feeling whatever he sees within its frame. Some things draw from him the flickers of excitement, others might make him laugh if only the voice the Maker gave him were capable of forming that sound. Still others evoke in him something like desire, and yet even this only swells to a blunt sort of prurience, an itch barely worth scratching. Mostly though, he feels a kind of frustration which almost rises to anger. But not anger that demands action. Just enough to feel a slight twist in his heart which never fully unwinds. And so his heart is by now quite contorted. And this frustration is the feeling he is left with each day. This frustration is at least a feeling. And as the Voice has told him: ‘Feeling is important. Feeling means you are alive.’

But the Rat is mistaken. Because this day is not the same as all the others after all:

Before the Window appears, all at once he hears another sound. A faint scratching coming from the door. He looks over - although of course, in the gloom, he cannot expect to see much. But to his surprise, he does see, quite clearly, a small creature squeezing itself, with some considerable effort, under the foot of the door. The outlines of it are distinct. As if it carries its own light with it, since nothing else within the Rat’s cell could illumine it so well. It is a mouse.

Bold as you like, the mouse comes right up to where he lies. And after regarding him with bright, blinking eyes for a moment or two, it says: ‘Wake up.’

‘I am awake,’ replies the Rat.

‘No, indeed, you are not, my friend. I say again, awake!’ This time the mouse speaks with real force, in a voice that belies his little size.

The Rat is now confused as well as surprised by this intrusion. ’Who are you? What are you doing here?’

‘I have been sent to help you. Who I am is of no import when laid against who you are.’

‘What can you mean? I am of no importance. I am a rat and this is where I belong. It is you, Mouse, who needs explaining.’

‘No, no. I say again, no!’

‘No?’

‘You are no rat. That is why I am sent to you.’

‘What folly is this? I am no rat?’ And for the first time, he experiences the undoubted pleasure of real indignation. ‘Are you mad? Have you lost your senses? See, here are my paws. There is my tail.’

And yet, even as he proffers them, he is surprised to see the shadow of his smooth little hands seem now not quite so smooth and altogether swollen, nor is the length or girth of his hairless tail quite as he remembers it. But he dismisses these as mere tricks of the gloom and his own agitation at so abrupt and strange an interruption.

‘If I told you what you truly are,’ answers the mouse, ‘you would neither understand nor believe me. Only this must you accept: you do not belong here. And where you do belong desperately needs you. So I have come to wake you up.’

‘Again this idea that I am asleep,’ returns the Rat, scratching confusedly at his nose. ‘As if you are some apparition in a dream—‘

‘Not asleep, but enchanted,’ interrupts the mouse. ‘Enthralled and silenced. It is your voice that is needed, and your heart.’

‘My voice?’ squeaks the Rat. ‘What possible use can anyone have for my voice? And anyway I am not silenced. I could speak as much as I wish. I just have nothing much to say.’

The mouse seems distracted then. His little ears twitch and turn. ‘Quickly, we have not time to bandy words. Only rise and follow me.’

‘Follow you where?’ scoffs the Rat. ‘See, I’m thrice the size of you and cannot go by the way you came in. This cell is sealed to me. Besides which, these chains—’

‘You will see,’ urges the mouse, impatient with his protestations. ‘The door is not truly barred. Those chains do not truly hold you. Indeed there is no prison. I say again, rise. Come and you will see all that you are meant for and all that is meant for you.’

But before any more can be said or done, a sound suddenly fills the dingy place: ‘Is that you, Mouse, you troublesome little beast?’ It is the Voice - and far sharper and angrier than the Rat has ever heard it.

The Rat shrinks back against the wall. But the mouse lifts his nose defiantly. ‘It is not I who is trouble-maker here, but you, Spell-Spinner. Truth-Twister. Usurper.’

‘Usurper?’ The Voice chuckles, a languorous, malevolent sound. ‘Is not this my kingdom? Are not you the intruder here?’

‘You have no kingdom and no authority but which you have stolen through your lies and deception.’

‘Lies? Deception? I tell no lies. I offer no deception. It is you and your…your vermin kind who stir up trouble inviting people to believe that which is not. You conjure pretty dreams to lure weak minds into your thrall out of the mere imaginings of a diseased brain.’

‘You lie as easily as you breathe,’ returns the mouse, glaring about him.

‘Come now, where is the lie?’ soothes the Voice from its aperture.

‘All around us. This very place.’

‘Nonsense. This is real. I only show those who dwell here what is true, the better for them to accept their reality. I - we - who are given charge of this place know that the first sign of a mind turning to disease is the thought that there must be something else. That this is not exactly where they belong and who they are—’

The mouse appears to lose patience then and turns back to the Rat. ‘Listen not to this voice a moment longer, but harken only to me. Awake, arise. Follow me. Come, we must away.’

And so surprised at the steady authority in the mouse’s words, the Rat find himself uncoiling from his cringing corner and indeed getting to his feet, so that he begins to follow the mouse towards the door, despite the weight of his chains, and though he knows it is bolted and barred. They are nearly at it when another voice, much closer, cries out of the shadows: ‘Stop where you are, Rat!’

Terrified, for an instant, the Rat obeys. He looks back and see a far larger shadow moving in the gloom now. And before he can even wonder whence it has appeared, the shadow leaps and in two quick bounds overtakes the two little rodents and stands between them and the door.

The Rat sees now it is a cat. An especially large and especially black cat, with long silvered whiskers and a coat that is soft and shining as velvet.

‘I warned you what would happen if you came back, little beast,’ the cat says, addressing the mouse. ‘There is none more dangerous nor more harmful in all my kingdom than you.’

The mouse, brave little creature, stands back upon its hind legs, drawing itself up to its fullest height, which is by no means saying much against the overbearing presence of the cat. ‘It is not your kingdom,’ hisses the mouse in defiance. ‘And even though you strike me down, others will come in my place.’

‘Oh, I hope so,’ says the cat, an insidious smile in his voice. ‘For I do so enjoy a little nap on a full belly.’

And with that, the cat pounces. There is a brief scuffle in the gloom, a solitary squeal, then the cat is sitting back on its haunches. For a moment he paws at a shapeless lump on the ground before him. Then with sudden relish, he falls upon the wretched mouse, gobbling it up from nose to tail until there is no sign that it has ever been there. But for the flicker of the cat’s pink tongue, licking the last of its blood from his lips.

Sated, he turns back to the Rat.

‘Sometimes, Rat, it becomes necessary for you to see me as I really am,’ he says, his tone languid now. ‘But that is not altogether regrettable. Now you can see I am telling the truth. Now you can have no doubt. You see that I, at least, am real. Real enough to rid us both of that meddlesome brute.’

‘But…but what he said,’ the Rat dares to whisper, though still gripped with shock, and not a little terror, at the strange turn of events. ‘Can there be nothing to them? A madman may see a distortion. But only a distortion of something that is there—’

‘Listen to me,’ the cat quickly hissed, standing over the Rat. ‘And heed me well. Have I not thought only of your good, Rat? Do I not give you food to ease your hunger? Do you not live secure and well in this place? By the stars, I even keep you entertained! Is all this not enough for you? How would a rat like you fare in any other place, even if such a place did exist?’

To this, the Rat has no answer. The cat gives a little chuckle. ‘Quite so. Now, the little mouse is done with. And with him, his mad imaginings. We must stop them from infecting any others, for it will only lead to distress and dissatisfaction. This is not my wish for you,’ the cat purrs silkily, and as he does, a sort of drowsiness starts to creep over the Rat. ‘Be happy with your lot. He who can master this can master all. Even you, Rat, can be master of this life, if you do.’

The cat drops to its paws, its yellow eyes now level with the Rat’s, set in a glare as hard as stone. His nose so close, the Rat can smell the mouse’s blood upon his breath. ‘Forget the mouse. When all is said, he was nothing but a dainty little morsel for me to eat.’

Something in the cruelty of the purring voice just then, in the way the cat licks its lips lasciviously once more - something in the memory of the little mouse who, for all his strange urgings, clearly meant kindness towards him - stirs in the Rat’s heart more than regret, more even than fear. A sudden, white hot rage grips him dispelling in an instant the drowsiness that has come over him. And before he knows quite what he is doing, the Rat raises his little paw and swipes the cat smack across his pink nose with all the force he can muster.

He knows it can be but a futile gesture which will only bring him trouble, but to his amazement, the cat is flung across the cell, hitting the wall with such force that he falls limp and unmoving to the floor. For a moment, bewildered, the Rat thinks the cat is dead, or else he himself is dreaming. But then slowly the cat picks itself up, shakes itself, casts him a final look of slavish terror, then flees, disappearing through some unseen hatch as quickly as he had come.

The Rat looks down in wonder at his paw, mystified at the strength in it.

And yet, what he sees now is not the familiar pink pads of a rat’s paw, with the fragile little nails that he is used to, but something altogether bigger, stronger, fiercer. Covered in hair, with black claws long as his tail. Astonished, he gets to his feet. And so doing, his whole body feels heavier, and yet holds within itself a new strength to move. The weight of his chains, he notices not at all.

He turns now to the door, suddenly determined to discover what lies beyond its bolts and bars. But when he goes to it and raises his paw to push against it and test its resistance, his paw goes right through it. There is no resistance. There is nothing there. And all at once, the walls and floor and low cramped ceiling of his cell melt away until he finds himself standing in a new sort of darkness. One that feels expansive, that has no limits.

No, not quite darkness. There is a source of dim light now giving some shape to the things around him. It seems far off though, and high. He wants to go to it. He takes a step forward, and as he does, he is suddenly overcome with a violent choking. He drops his head, gasping for breath, his great back heaving with strain as something jagged and hard rises in his gorge. And next moment, he is vomiting up something into the soft ground at his feet. At once he feels lighter, he feels his breath coming more freely in thick rasping pants. There at his feet lies an ugly object indeed. It is a kind of misshapen metal ball covered in a multitude of sharp spikes, and he wonders in disgust that such a thing could be lodged unknown in his throat for so long.

But it is out now, and he feels all the better for it.

Now he walks towards the faint glow above and beyond him. The ground is soft beneath his paws. He seems to be climbing through a landscape which he can see but dimly at first. There is a great openness above him. In the growing light, shapes take form and with them the memory of things long, long forgotten. Maybe things he never really knew but only dreamed of once. Alien and yet at once familiar. Trees and rocks and other forms stirring in the gloom. There is much he cannot see, but he is not afraid. Indeed he feels no fear at all now, only a kind of growing expectation, a growing certainty of what he must do.

And so he climbs and climbs.

At last he sees the line of a ridge above him. He sets himself to the task of scaling this last, highest hill. And though he walks in shadow still, the sky above him is filling with light. It turns in colour from grey to white to coral pink. And as he pads the last few paces to the summit, a feeling swells inside of him, a long hidden explosion of sound and emotion. The very cry of his heart.

He is there now. He looks out across an endless landscape below him.

And as the first rays of a mighty dawn race over the distant purple hills, the lion’s roar rings out across the land. At the sound of it, all the sleeping animals awake and prick up their ears.