In the recent horror-thriller Heretic, Hugh Grant plays Mr. Reed, a sharp-witted psychopath who imprisons two missionaries, subjecting them to ceaseless diatribes about the supposed irrationality of all religions. Mr. Reed is also a terribly smug, self-righteous bore, a caricature of the fervent atheist who dismisses faith as mere superstition while assuming atheism is objective and neutral.

This kind of assumption lies behind the criticisms directed by secularists at those who argue from a position of faith, as we saw recently with the debates on the Assisted Dying Bill. Yet, the notion of secular objectivity is itself a fallacy. Secularism, like any worldview, is a perspective, ironically one that is deeply indebted to Christianity, and humanity’s history of abandoning faith and its moral foundation has had disastrous consequences.

Secularism is a bias, often grounded in an ethical vanity, whose supposedly universal principles have very Christian roots. Concepts like personal autonomy stem from a tradition that views life as sacred, based on the belief that humans are uniquely created in God's image. Appeals to compassion reflect Jesus’ teachings and Christian arguments for social justice throughout history. Claims that the Assisted Dying Bill was "progressive" rely on the Judaeo-Christian understanding of time as linear rather than cyclical. Even the separation of the secular and sacred is derived from Jesus’ teaching to “render to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s”. Authors like Tom Holland in Dominion and Glen Scrivener in The Air We Breathe have shown how Western societies, though often disconnected from their Christian roots, still operate within frameworks shaped by centuries of Christianity.

The antidote to human pride and self-deception was to be found in the Almighty. Ironically, it was this humility, rooted in a very theological concern about human cognitive fallibility, that gave birth to the scientific method.

A political secularism began to emerge after the seventeenth century European religious wars but the supposed historical conflict between science and religion, in which the former triumphs over superstition and a hostile Church, is myth. Promoted in the eighteenth century by figures like John Draper and Andrew White, this ‘conflict thesis’ persists even though it has been comprehensively debunked by works such as David Hutchings and James C. Ungureanu’s Of Popes and Unicorns and Nicholas Spencer’s Magisteria. Historians now emphasize the complex, often collaborative relationship between faith and science.

Far from opposing intellectual inquiry, faith was its foundation. Medieval Christian Europe birthed the great universities; this was not simply because the Church had power and wealth but because knowledge of God was viewed as the basis for all understanding. University mottos reflect this view: Oxford’s "Dominus illuminatio mea" (The Lord is my light), Yale’s "Lux et Veritas" (Light and Truth), and Harvard’s original "Veritas Christo et Ecclesiae" (Truth for Christ and the Church). This intertwining of faith and academia fuelled the Enlightenment, when scientists like Boyle, Newton, and Kepler approached the study of creation (what Calvin described as ‘the theatre of God’s glory”) as an affirmation of the divine order of a God who delighted in His creatures “thinking His thoughts after Him”.

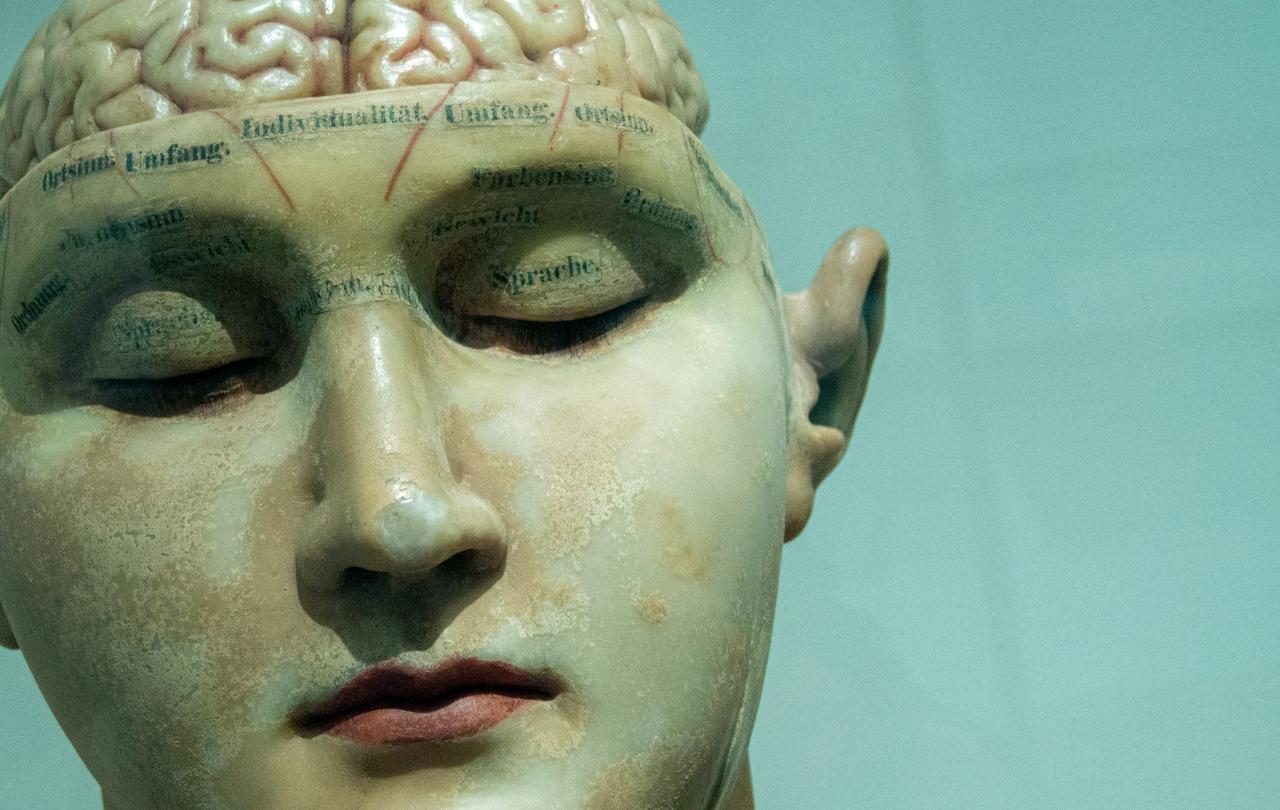

Their Christian beliefs not only provided an impetus for rigorous exploration but also instilled in them a humility about human intellect. Unlike modernity's view of the mind as a detached, all-seeing eye, they believed man’s cognitive faculties had been diminished, both morally and intellectually, by Adam’s fall, which made perfect knowledge unattainable. Blaise Pascal captures this struggle with uncertainty in his Pensées.

“We desire truth, and find within ourselves only uncertainty....This desire is left to us, partly to punish us, partly to make us perceive from whence we have fallen.”

For Pascal and his believing contemporaries, the antidote to human pride and self-deception was to be found in the Almighty. Ironically, it was this humility, rooted in a very theological concern about human cognitive fallibility, that gave birth to the scientific method, the process of systematic experimentation based on empirical evidence, and which later became central to Enlightenment thinking.

Orwell was not alone in thinking that some ideas were so foolish that only intellectuals believed them.

Although many of its leading lights were believers, the Enlightenment era hastened a shift away from God and towards man as the centre of understanding and ethics. Philosophers like David Hume marginalized or eliminated God altogether, paving the way for His later dismissal as a phantom of human projection (Freud) or as a tool of exploitation and oppression (Marx), while Rousseau popularised the appealing idea that rather than being inherently flawed, man was naturally good, only his environment made him do bad things.

But it took the nihilist Nietzsche, the son of a Lutheran pastor, to predict the moral vacuum created by the death of God and its profound consequences. Ethical boundaries became unstable, allowing new ideologies to justify anything in pursuit of their utopian ends. Nietzsche’s prophesies about the rise of totalitarianism and competing ideologies that were to characterise the twentieth century were chillingly accurate. Germany universities provided the intellectual justification for Nazi atrocities against the Jews while the Marxist inspired revolutions and policies of the Soviet and Chinese Communist regimes led to appalling suffering and the deaths of between 80 and 100 million people. Devoid of divine accountability, these pseudo, human-centred religions amplified human malevolence and man’s destructive impulses.

By the early 1990s, the Soviet Union had collapsed, leading Francis Fukuyama to opine from his ivory tower that secular liberal democracy was the natural end point in humanity's socio-political evolution and that history had ‘ended’. But his optimism was short lived. The events of 9/11 and the resurgence of a potent Islamism gave the lie that everyone wanted a western style secular liberal democracy, while back in the west a repackaged version of the old Marxist oppressor narrative began to appear on campuses, its deceitful utopian Siren song that man could be the author of his own salvation bewitching the academy. This time it came in the guise of divisive identity-based ideologies overlayed with post-modern power narratives that seemed to defy reality and confirm Chesterton’s view that when man ceased to believe in God he was capable of believing in anything.

As universities promoted ideology over evidence and conformity over intellectual freedom, George Orwell’s critique of intellectual credulity and the dark fanaticism it often fosters, epitomized in 1984 where reality itself is manipulated through dogma, seemed more relevant than ever. Orwell was not alone in thinking that some ideas were so foolish that only intellectuals believed them. Other commentators like Thomas Sowell are equally sceptical, critiquing the tenured academics whose lives are insulated from the suffering of those who have to live under their pet ideologies, and who prefer theories and sophistry to workable solutions. Intellect, he notes, is not the same thing as wisdom. More recently, American writer David Brooks, writing in The Atlantic, questions the point of having elite educational systems that overemphasize cognitive ability at the expense of other qualities, suggesting they tend to produce a narrow-minded ruling class who are blind to their own biases and false beliefs.

It was intellectual over-confidence that led many institutions to abandon their faith-based origins. Harvard shortened its motto from "Veritas Christo et Ecclesiae" to plain "Veritas” and introduced a tellingly symbolic change to its shield. The original shield depicted three books: two open, symbolizing the Old and New Testaments, and one closed, representing a knowledge that required divine revelation. The modern shield shows all three books open, reflecting a human centred worldview that was done with God.

However, secular confidence seems to be waning. Since the peak of New Atheism in the mid-2000s, there has been a growing dissatisfaction with worldviews limited to reason and materialism. Artists like Nick Cave have critiqued secularism’s inability to address concepts like forgiveness and mercy, while figures like Ayaan Hirsi Ali and Russell Brand have publicly embraced Christianity. The longing for the transcendent and a world that is ‘re-enchanted’ seems to be widespread.

Despite the Church’s struggles, the teaching and person of Christ, the One who claimed not to point towards the truth but to be the Truth, the original Veritas the puritan founders of Harvard had in mind, remains as compelling as ever. The story of fall, forgiveness, cosmic belonging and His transforming love is the narrative that most closely maps to our deepest human longings and lived experience, whilst simultaneously offering us the hope of redemption and - with divine help – becoming better versions of ourselves, the kind of people that secularism thinks we already are.

Join with us - Behind the Seen

Seen & Unseen is free for everyone and is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you’re enjoying Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Alongside other benefits (book discounts etc.), you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing what I’m reading and my reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief