My old RE teacher always liked to make the point that meaning can be found in anything, if you want to find it.

“Do you find meaning in a sunset?” he’d ask. “Or only beauty?”

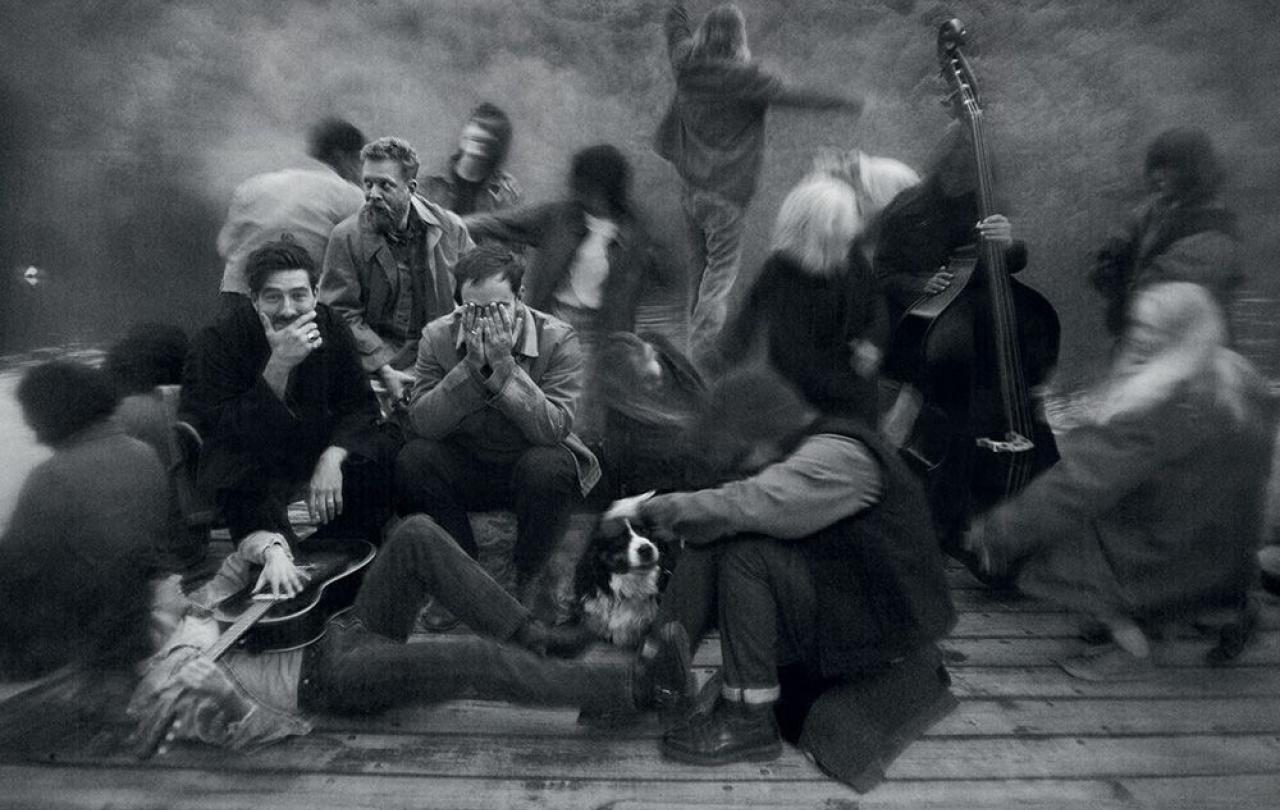

From the outset of Mumford & Sons’ new record, ‘Rushmere’, the deeper things, as ever, are front and centre - at least for those of us who wish to find them.

The folk band’s records have always been replete with religious undertones - lead man Marcus Mumford is the son of a preacher, don’t you know? - and they are apparent from the very start of the band’s fifth studio album and first since 2018.

‘Rushmere’ kicks off with ‘Malibu’, which speaks of finding “peace beneath the shadow of your wings”, and an unnamed “you” being “all I want” and “all I need”.

There’s even talk, right at the beginning of the song, of feeling “the spirit move in me again - the same spirit that moves in you”.

Precisely which spirit is meant is never defined - these are song lyrics, after all, not a sermon - but for this listener at least, the reference to the third member of the Trinity appears clear.

Not every song on the album hits such obvious religious notes, but the opening track is far from unique. Indeed, one needs only to flick through the names of the other songs to get a hint of the deeper meanings on offer, with titles such as ‘Truth’, ‘Anchor’ and ‘Surrender’.

Meanwhile, in ‘Monochrome’, we’re told that even within a hyacinth can “life”, “restoration” - even “Christ” - be found.

Could the “out of sight” monochrome “beyond reason” that we are called to contemplate represent the Christ - in theological terms, the “Word” of God - whose fingerprints can be seen across Creation?

And what is meant when Mumford sings that “the kind of love that I’m always chasing is the kind of love that won’t be chased?”

As with many of the band’s lyrics, there appears space for both a romantic and religious reading, though perhaps romance is harder to read into metaphors such as a “cup running dry”, as Mumford sings elsewhere in ‘Monochrome’.

Is it only me for whom this evokes memories of the old Sunday school refrain: “Fill up my cup and let it overflow”?

‘Truth’, meanwhile, begins with the fairly blunt statement: “I was born to believe the truth is all there is.”

“Oh my love, hold me fast,” the song ends, and again we are left to wonder about which love he is singing - earthly or divine.

It isn’t made clear whether such belief remains intact today, nor even which truth is meant, given that we now live in times where such things seem occasionally grey. But ‘Surrender’ appears more black and white, speaking of being brought to one’s knees, “broken” then “put back together”, and “held in the promise of forever”.

“I surrender, I surrender now,” Mumford cries - words Christian congregations have sung for centuries.

And as ever with a Mumford & Sons record, ‘Rushmere’ doesn’t hold back from the trickier theological issues, touching upon the concepts of both hell and original sin.

“Let your anger go to hell,” ‘Where It Belongs,’ Mumford sings in the track of the same name, which is sung like a lament, while in the final track, ‘Carry On’, those of us who believe in original sin are encouraged to consider that “there’s no evil in a child’s eye”.

“It was made, and it was good,” Mumford sings in a nod to the Creation story, when the world was blemish-free.

Meanwhile, in ‘Anchor’, Mumford sings that he “can’t say he’s sorry if he’s always on the run from the Anchor”. Which for some of us, at least, will conjure recollection of part of the Bible’s Book of Hebrews that speaks of our “hope” - Jesus - being “an anchor for the soul, firm and secure”.

“Oh my love, hold me fast,” the song ends, and again we are left to wonder about which love he is singing - earthly or divine.

Fans of Mumford & Sons - and yes, you’ve guess it, I count myself among them - will recognise that particular phrase from a previous hit, ‘Hopeless Wanderer’, which again seemed to speak to a life of faith; of pilgrims “called by name” trying “so hard to live in the truth”, but being “prone to wander”, as it says in the hymn ‘Come Thou Fount’, which Mumford has also been known to perform.

So this is not the first Mumford & Sons album to have contained such imagery. Far from it. For those of us who’ve followed the band since their debut album, ‘Sigh No More’, in 2009, there have always been calls to ‘Awake My Soul’ or to find comfort in a future day in which there will be “no more tears.”

In the years since, we have been encouraged to be ‘Lover[s] of the Light’, or to find hope in a ‘Guiding Light’ who won’t ‘Slip Away’ in the night.

Perhaps, then, there’s nothing very different about ‘Rushmere’ - it represents just another chapter on a journey of faith - but this particular fan continues to appreciate, deeply, the depth that Mumford and his bandmates continue to bring to our ears.

And as for the music, well I suppose by now that most readers will probably be familiar with what one can expect from a Mumford & Sons album, and ‘Rushmere’ certainly doesn’t disappoint those of us who like that kind of thing.

It’s notably shorter than the previous album - nearly half the length - but is probably no worse for it. It’s hard to think of a weak song on the album, while there is something for everyone: from the country feel of ‘Caroline’ (think Counting Crows/Ryan Adams) and rock and roll of ‘Truth’, to the gentle fingerpicking and harmonies of ‘Monochrome’. Heck, the banjos even make a comeback on the self-titled ‘Rushmere’, so truly something for everyone - or at least for all of us fans.

By the way, my old RE teacher never told us what he believed, but I later found out that he’d once been ordained, so I suppose that he, like me, might still find meaning in a sunset or even, perhaps, a Mumford & Sons record.

Celebrate our 2nd birthday!

Since March 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,000 articles. All for free. This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief