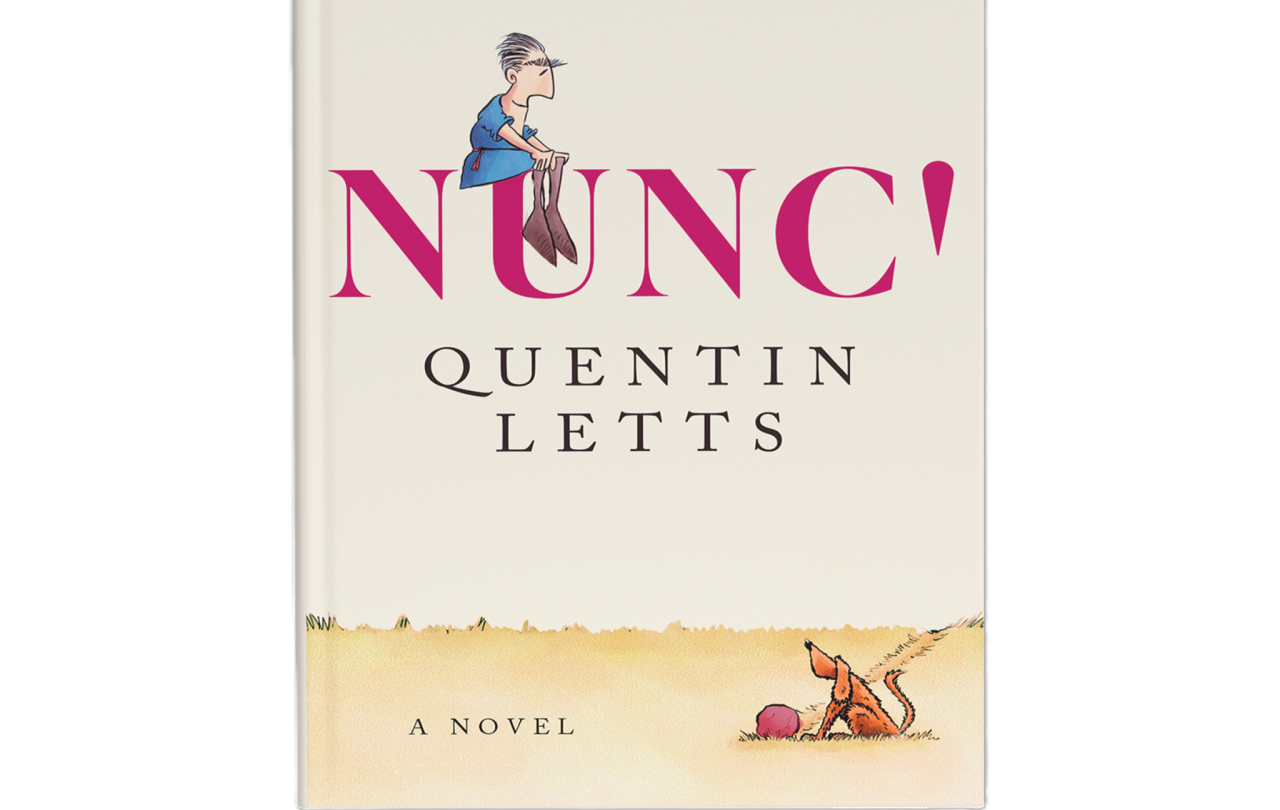

Historical fiction is my favourite genre of novel. Make it biblical historical fiction and you’ve sold me before I’ve cracked the spine! I bought a copy of Quentin Letts’ NUNC! without having read a single review or knowing anything about it… and what a sensible decision it was. Letts has produced a novel that combines his rapacious satirical wit, theological and historical acumen, and a beautiful sentimentality – the novel is dedicated to his brother Alexander, who died of cancer.

It is inspired by the words of the Nunc Dimittis, as translated in the Book of Common Prayer. Sung by Simeon, as he holds the Christ child in his arms, they are words that are full of joy, because God has promised Simeon that he will not die until he has seen the Messiah. “Lord, now lettest thou now thy servant depart in peace,” it begins: words that are spoken or sung at every Evening Prayer in the Church and have provided hope and comfort for generations.

The novel opens with the character of Symons (no, I didn’t misspell it), a titanic literary concoction of corduroy, wax jacket, and mild middle-aged irritation, who lives in a classical English cathedral town. He receives a terminal cancer diagnosis. He has an argument with his wife, Anne (the typology is strong in this novel). He gets pissed. As he totters home from his local wine bar, he passes the cathedral and is captivated by the sound of singing.

Upon entry he realises the choir is rehearsing the canticles for Evensong. He hides behind a pillar and kneels down in a pew. The Nunc Dimittis is rehearsed, and the heady combination of high emotion and fine wine sends him into a prayerful stupor. We are transported to first century Jerusalem and spend most of the rest of the novel in the company of Simeon and a cadre of his friends, acquaintances, and opponents.

What follows is a series of hilarious vignettes, featuring a wide array of brilliantly sketched characters. Spending much of our time in ‘Deuteronomy Square’ we meet Rueben the tea seller, Tambal the slave (who has a fondness for Roman cuisine and a horrid aversion to gefilte fish), Noor the mad garlic seller, Jonah the hypocritical Pharisee, and Shlomo the dog. Through them, and many others, Letts allows the reader to explore the social, political, religious, and dietary life of the inhabitants of Jerusalem.

The humour never vanishes, the confessional power never overwhelms, the lightness of touch is always present; and yet the novel takes on a new intensity...

How did the Judeans feel about the Romans? Were there ever friendships between Jew and Gentile oppressor? How did the average man or woman feel about Herod? What was their attitude to a priestly and religious hierarchy? Were the Wise Men buffoons? Letts weaves such themes through a narrative laden with the humour and heart-warming episodes that mark the best ‘slice-of-life’ writing. The people of first century Jerusalem might be separated from us by time, space, language, culture, and cuisine, but their highs and lows, their gripes and loves, their daily search for happiness and meaning, are no different to ours.

Underpinning the story is Simeon’s daily watch for the promise of the Christ. Letts has ten verses from the Gospel of Luke as a foundation to build his protagonist, and four of these are a song. Undeterred, Letts uses Simeon as a cypher to explore further and deeper themes: youthful indiscretion, regret, passion, love, shame, faith, doubt.

Letts also allows for a certain frisson of imaginative licence to round out his back-story. What was Simeon’s profession? Who were his parents? Did he know Anna the Prophetess? Why had God given him this task of watching and waiting, praying and hoping? Never overexplaining or labouring the point, Letts grants the reader a few moments of memory and introspection from the old man, but otherwise invites us to understand Simeon through his daily dealings with those around him.

By the end of the novel we have not only one of the funniest characters of modern fiction, but one of the most spiritually and emotionally complex. I prepared to leave Simeon – encountering Mary, Joseph, and the infant Christ – feeling as if he was a member of the family.

Letts concludes the novel with Simeon’s great biblical performance: ten verses which suddenly take on a remarkable poignant weight. The novel quietly switches gear to become a theological meditation worthy of any spiritual writer. The humour never vanishes, the confessional power never overwhelms, the lightness of touch is always present; and yet the novel takes on a new intensity and seriousness that took me by the hand and led me to look upon the mystery of life, death, truth, beauty, and goodness.

It took me a while to make it through the final two chapters…my eyes kept misting with tears.

If you only read one novel this year, please let it be NUNC!

Celebrate our 2nd birthday!

Since Spring 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,000 articles. All for free.

This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief