Clean, calm and collected,

That’s how it would have been.

The stable of filtered imaginings,

A picture perfect scene.

Perhaps more messy -

Undignified, unexpected, unseemly -

A not-so dream-like site,

As a king’s birthing barn that night.

Our unimagined stable.

No perfectly planned polaroid,

But in mess, mud, blood,

Is God with us

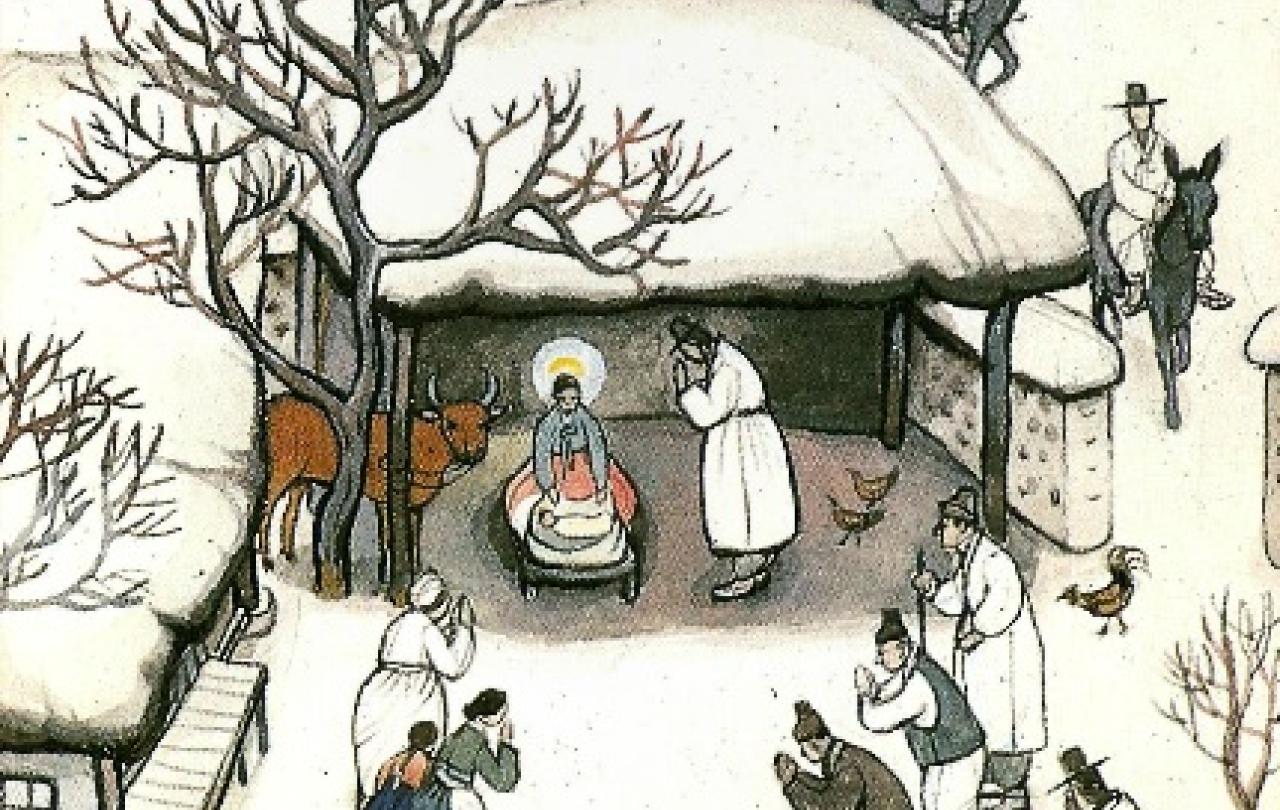

The stable of our Christmas cards, illuminated shop window scenes, and our children’s nativity plays is neat and tidy. A newborn babe lies quietly sleeping in a straw-filled trough, wrapped perfectly in a Persil white blanket. The mother, clothed and clean, looks on adoringly, standing over her child. Any animals present are gentle, still, and lying on the ground, unaffected by this unusual occurrence in their home. This is the stable of our imaginations.

However, the Bethlehem stable was the delivery suite for the Saviour of the world. And even a Saviour’s birth includes mess. I have experienced a variety of delivery rooms over my three pregnancies and each one has been messy. From birthing pool to theatre there is noise, blood, water, and tears. Birth is messy. And that’s not even beginning to acknowledge the mess that would have been in the stable to begin with! Despite this, the stables we see and celebrate never include the mess that Jesus would have been born into.

Birth is also extreme. It pushes the woman’s body to the limit of her physical and emotional capacity. She has laboured - aptly named for it is indeed hard work. Her body has been torn to enable this little life to be pushed or pulled into the world. She is exhausted. And now the work begins to sustain this little one outside of the womb. While inside he has been given all that he needs, now outside they must learn together how to feed. As the newborn babe is held close to his mother, he recognises her rhythmic heartbeat, his temperature regulates, his smell and touch encourages her milk to develop, and as he feeds, he contracts her womb for the placenta to be born and her body to begin to heal. They are still dependent on each other in these early hours.

Usually, this extreme and messy moment is done in community. It is not something we embark on alone. We have a support network of skilled people to help and guide us through birth. We have birth partners who encourage us, champion us, and remind us of our body’s innate ability to birth this baby. But Mary did not have this normal group of cheerleaders. There were no midwives at her birth, no older women who had walked this path before. Only her new husband, afraid and unsure of what his young wife was about to do. And then soon after, the Shepherds arrived. A bunch of slightly smelly, nocturnal chaps walking into a delivery room. Although they would have been familiar with mess, noisy animals, and birth, I’m not sure I would have rejoiced at their unexpected arrival. Somehow though, Mary graciously welcomes them into the space of what was probably a very messy stable.

Perhaps instead of the sanitised stable of our imaginations, we might consider an alternative imagining - the messy stable of the Saviour. A stable where the humanness of birth, of mother and child, and of life’s mess is fully felt. Because it was into the mess, grit, and dirt that the Saviour came. And it was from this mess that he was going to save.

Join with us - Behind the Seen

Seen & Unseen is free for everyone and is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you’re enjoying Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Alongside other benefits (book discounts etc.), you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing what I’m reading and my reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief