The Bough Breaks by Matthew Krishanu at Camden Art Centre has been described as the most significant exhibition of his work to date because, by showing the drawings and works on paper that he calls the generative heartbeat of his work as well as the works for which he is best known, the exhibition is the fullest expression to date of the expansive world of his artistic practice.

His images are primarily personal stories told through layers of memory, imagination, and conversations with the history of painting, in atmospheric, pared-back compositions which focus particularly on his childhood years in Bangladesh growing up with his brother, and their parents who were a British Christian priest and a Bengali theologian.

He speaks of his images in terms of an ‘I-you-them‘ axis. The work he considers his first painting, from 2005, entitled ‘Boy on a Bed’ was originally a scene of an empty room. He recalls that “late in the night before I was going to be exhibiting it, I sketched in this boy with black hair, brown skin, and a little toy car behind him”. He continues, “I knew that was me, and I knew that there was something I wanted to communicate about the inner world of that child”. In 2012, there came another “fundamental shift” in that “I wanted to paint myself and my brother”. With the first ‘Two Boys’ painting, “I remember it felt like worlds had opened up”. He explains that “when you have a single child, you can project ideas of melancholy or loneliness” but “when you have two, they outnumber the single viewer” and “I think the fact that they are clearly brothers and both have brown skin and often a very direct gaze at the viewer, holds a certain power”.

He recalls being in a show called Painting Childhood: From Holbein to Freud where the very last room was of the ‘Two Boys’: “Having gone through room after room of European children, white children, then coming into a room where these two boys weren't othered in any way, but were taking centre stage in the narrative, was hugely important.”

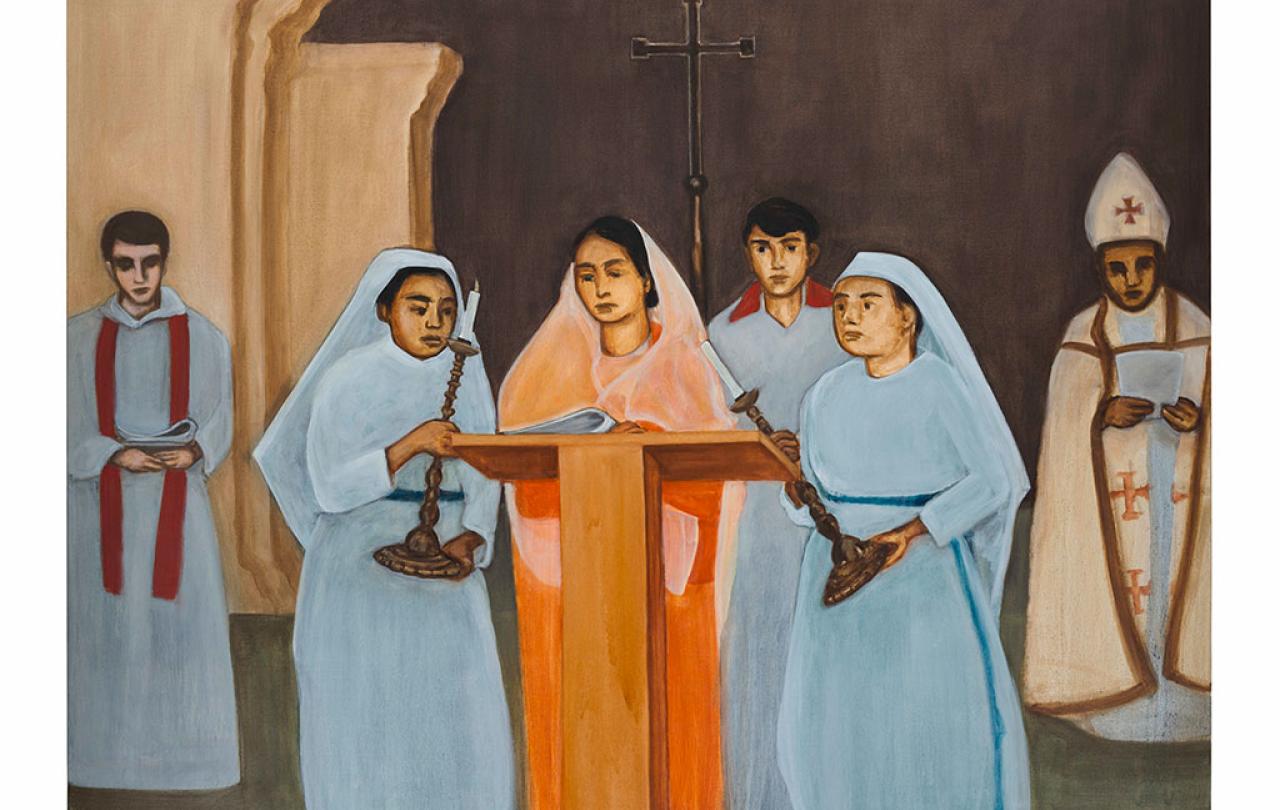

Adults are excised from the ‘Two Boys’ series “because I want the boys to be out on a limb or up on a hill, without parental supervision”. However, within the ‘Mission’ series - paintings of church life in Bangladesh - adults are seen from the perspective of children. As a result, they are in the ‘them’ part of the axis: “I see the adults in the third person. I'm constructing them as in some way other to the child's eye. This brings in the strangeness of performance and ritual, the stiffness of it too, particularly when you're used to being barefoot on the ground in Bangladesh and, suddenly, are meant to sit still and quiet. For me, it was compounded by the fact that I was brown skinned, as was my brother and mother, and my father was white skinned, and he was a priest, and he was a man, and all the power that comes with being a white man in Bangladesh; just the way he is perceived by his congregation, and even strangers on the street.”

He recalls that: At the time I knew that wasn't right and I didn't like the depictions of God as this white man flying around the sky. As a child, you have quite a raw and immediate relationship to life and nature and spirituality and, for me, it was the religious art that was the fundamental barrier to entering the world of the church. Also, the gendering of ‘Our Father’ or Jesus, the ‘only son’. That's why, as a young teen, I decided I didn't want to be confirmed, because I didn't believe in that construction.”

‘For me, that is where my faith is, in love, in the love of family, in all that a baby calls upon us to give it.’

In a painting like ‘Preaching’, he is exploring what it is to centre, in a congregation of brown adults and children, “the four nuns and my mother preaching with the two female candle holders and have the men on the sides”. So, “It's all about constructing a world which is both a counterpoint to the world of the two boys and nature, but also a counterpoint to the religious hierarchy we see in the church now”. The ‘Holy Family’ series, “which is of Bengali nuns, priests, and bishops” “is a deliberate response to the white depictions of Christ, baby Jesus, and Madonna”.

He notes that: “It's part of my painting mission to offer a counterpoint on the widest possible framing of an ‘I-to-you’ axis of a brown child, which isn't seen through the lens of National Geographic or Comic Relief ‘white saviours’, but is taken and centred as the heart of a human story. And if there's any spiritual message, then it's about that; of love, of the divinity of children and babies, and the divinity of our beautiful world, the ecological world of trees, water, glorious sunsets and sunrises, and all that comes with the human form.”

He thinks that this show has “set up a kind of a world philosophy” for him: “The core, the heart of the show, for me, is family, particularly of my late wife and my daughter. In and amongst the drawings, there are some pictures of our baby, and my late wife holding our baby or, indeed, holding the tree that my daughter is climbing. For me, that is where my faith is, in love, in the love of family, in all that a baby calls upon us to give it. That is the closest thing to divinity. I won't even use the word God because it's too masculine in our language. The closest thing to the divine, I sincerely believe, is in the eyes of children, is in the eyes of babies, particularly.”

He concludes by saying he would love to expand his practice further in the future, noting “a figure that has really resonated in a way I haven't felt before is the Palestinian priest Revd Munther Isaac and his ‘Christ in the rubble’ sermon”. However, his art always “needs to come from a personal connection to something I've conceptually explored; it needs to have that heart first of immediate one-to-one human connection”.

Matthew Krishanu: The Bough Breaks, 26 April - 23 June 2024, Camden Art Centre, London.