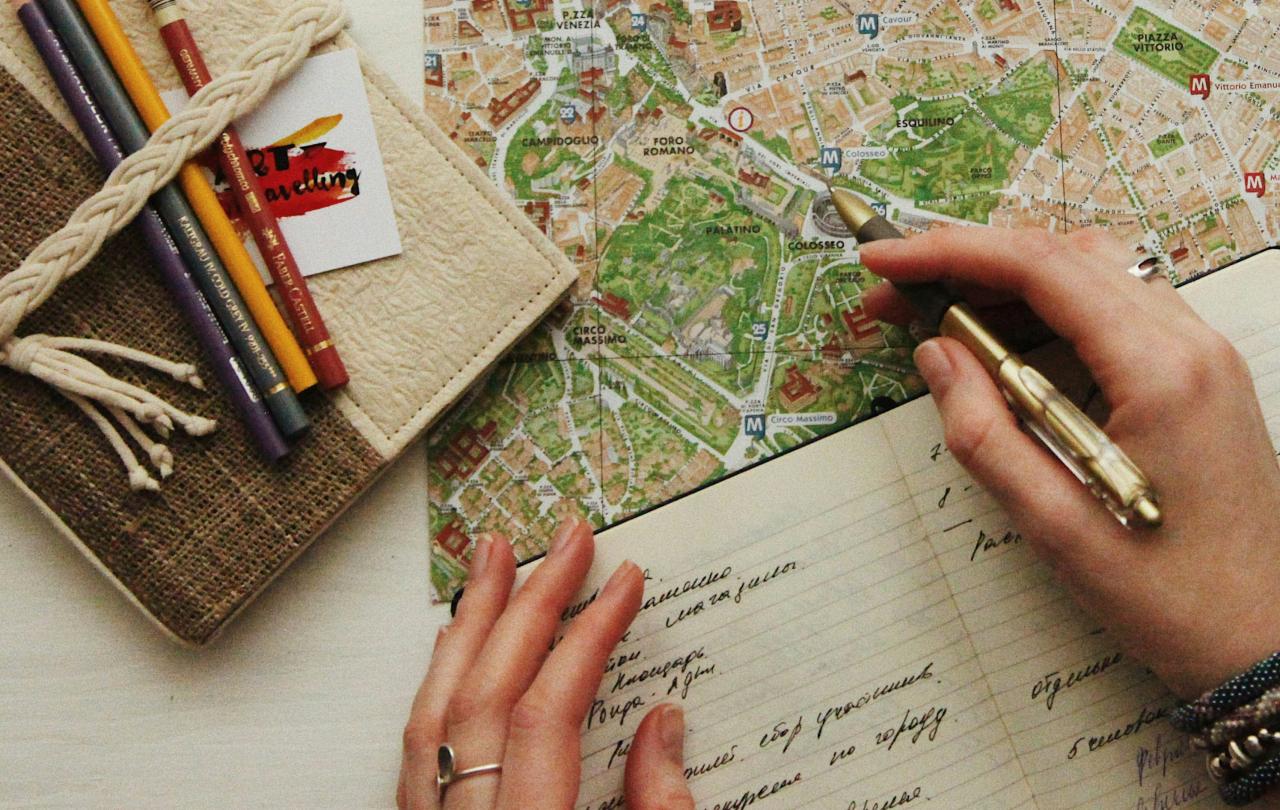

People first began to think about theology not because they were looking for intellectual stimulus or solutions to abstract problems, but because they found themselves living in an unsettling and vastly expanded ‘space’. They were conscious of new dimensions in their connection with each other, new dimensions in coping with their own fear, guilt, despair, a new sense of intimate access to the limitless reality of God. They connected these new experiences with the story of Jesus of Nazareth, executed by the Roman colonial government, reported by his closest friends as raised from death and present with them and their converts in the communication of divine ‘spirit.’ As we read Christian scripture, we are watching the first generations of Christian believers trying to construct a workable map of this unexpected territory.

When I started writing the assorted pieces that make up the little book on Discovering Christianity (published earlier this year), my hope was above all to convey something of this sense of Christian thinking as a process of mapmaking in a new and bewildering landscape. That’s why one chapter – originally drafted for a Muslim audience – tried to list some of the things that an interested observer might spot in looking from outside at the habits of Christian believers: not first and foremost their spectacular and uniform embodiment of unconditional divine love (if only), but just the sorts of things they said and did, the sort of language used about Jesus, the rituals of induction and belonging. Indeed, if there is one biblical text I had in mind in virtually all the chapters, it is the simple phrase, ‘Come and see’ that Jesus uses in St John’s gospel when he is first followed by those who will become ‘disciples’, literally ‘learners.’

‘Come and see’. When we use language like that in everyday life, we’re encouraging others to share something that has excited or troubled us (or both). It’s not a proposal for solving a problem. It’s not even a recruitment campaign. It’s an invitation to stand where someone else is standing and look from there. In the rich symbolic context of John’s gospel, it’s about sharing Jesus’ ‘point of view’ – which is, as we’re told right at the start of the gospel, a point of view unimaginably close to the heart of eternal life and reality itself.

We can only see in this way when we move away from our ordinary perceptions a bit. Just as we can only learn to swim when we have jumped into the water, so we shan’t learn what faith is all about until we have been prodded by whatever forces around us to take the risk of trusting that (so to speak) the ground is going to hold beneath us if we step forward (I like to speak sometimes about discovering what images, ideas, perspectives and relations are ‘load-bearing’ in our lives).

So part of the invitation is also about telling the stories of those who have taken that kind of risk and what sort of lives they have shaped for themselves in the light of it. There is little point in summoning others just to share my individual set of feelings. But there is perhaps more weight is saying, ‘A lot of people have felt this shape beneath the surface, this grain running through things.’ Which is why – as the book seeks to explain – theology works with the ‘classical’ shared texts that most Christian communities found themselves reading together in the first hundred years after Jesus; and works also with the history of the arguments and diverse perceptions that reading brought into focus.

We read and think in company; our theological reflection like the rest of our lives of faith is a shared, ‘conversational’ affair.

It's not unknown outside theology. We have become so much more interested over the last few decades in how to understand works of art not just in terms of what the artist ‘meant’, but in terms of what the actual work does or makes possible. What world does it create? So we read the Bible, obviously, but we also read the readers of the Bible (think of the Jewish Talmud, with the original text of its classical legal discussions literally surrounded on every page by the arguments that this text has generated). We read and think in company; our theological reflection like the rest of our lives of faith is a shared, ‘conversational’ affair. And so along with reading the Bible and immersing ourselves in the history of what sense others have made of the basic text and story, we also bring to bear the sorts of things that are part of our current conversations in society and culture – the habits of ‘reasoning’ that we have picked up.

There is an important difference between talking about ‘reason’ as a sovereign, detached capacity and talking about ‘reasoning’, the range of processes and practices that carry forward a common life of intelligent learning (and that learning may be at any level of supposed ‘intellectual’ capacity; once more, it’s not about abstractions). Our society these days is fairly comprehensively confused about this: we have a mythological picture of some supremely obvious way of arguing that allows for no final dispute; we call it ‘science’; and then we expect the impossible of it and are disillusioned and sceptical when it can’t give us absolutely certain answers. One of the many ironies of our society is that we are besotted with ‘science’ and at the same time fascinated by the idea that there are many ‘truths’, or else suspicious that apparently objective sources are actually controlled by other interests. Real ‘reasoning’ happens only when we have learned to trust one another’: a long story, but an all-important element in our human discovery.

Bible, tradition, human reasoning – those are the tools we bring to this job of mapmaking. The book is really just a meditation on those words, ‘Come and see’, as the basis of Christian thinking. At the centre of everything is a set of very ambitious claims about what God is like – and what we are like. Part of what we’re invited to ‘come and see’ is ourselves. Once again it’s not unlike what happens in a really good play or film, when we go away conscious that we have seen not just someone else’s story but something fresh about our own selves.

And my greatest hope for the book is that it may prompt someone to look a bit harder, to listen in to how Christians talk – and in that moment find that they recognize what’s being said in some complicated and untidy way. One of the most vivid characters in the gospel I’ve been quoting says of Jesus that he has told her everything she has ever done. I hope that those who are moved to investigate a bit further will come to that same unsettling and exciting point where they see themselves freshly, and the new landscape begins to unfold.

Celebrate our 2nd birthday!

Since March 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,000 articles. All for free. This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you’re enjoying Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief