Coronations point to the sacred nature of the United Kingdom monarchy. Packed with religious symbolism and imagery, they exude mystery, bind together church and state through the person of the monarch and clearly proclaim the derivation of all power and authority from God and the Christian basis on which government is exercised and justice administered. At their coronations kings and queens are not simply crowned and enthroned but consecrated, set apart and anointed, dedicated to God and invested with sacerdotal garb and symbolic regalia. Here, if anywhere, we find the divinity which, as Shakespeare observed more than four hundred years ago, hedges the British throne.

The United Kingdom is the only country which still marks the accession of a new monarch with a coronation. Of the other European monarchies, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands have never held coronations, Spain discontinued them in 1492 (they were not revived when the monarchy was restored there in 1975), Denmark in 1849 and Sweden in 1873. Norway abolished coronations in 1908 although since then its monarchs have undergone a ceremony of consecration or blessing in Nidaros Cathedral, Trondheim, with the royal regalia present in the church but not used in the ceremony.

Anglo-Saxon innovation

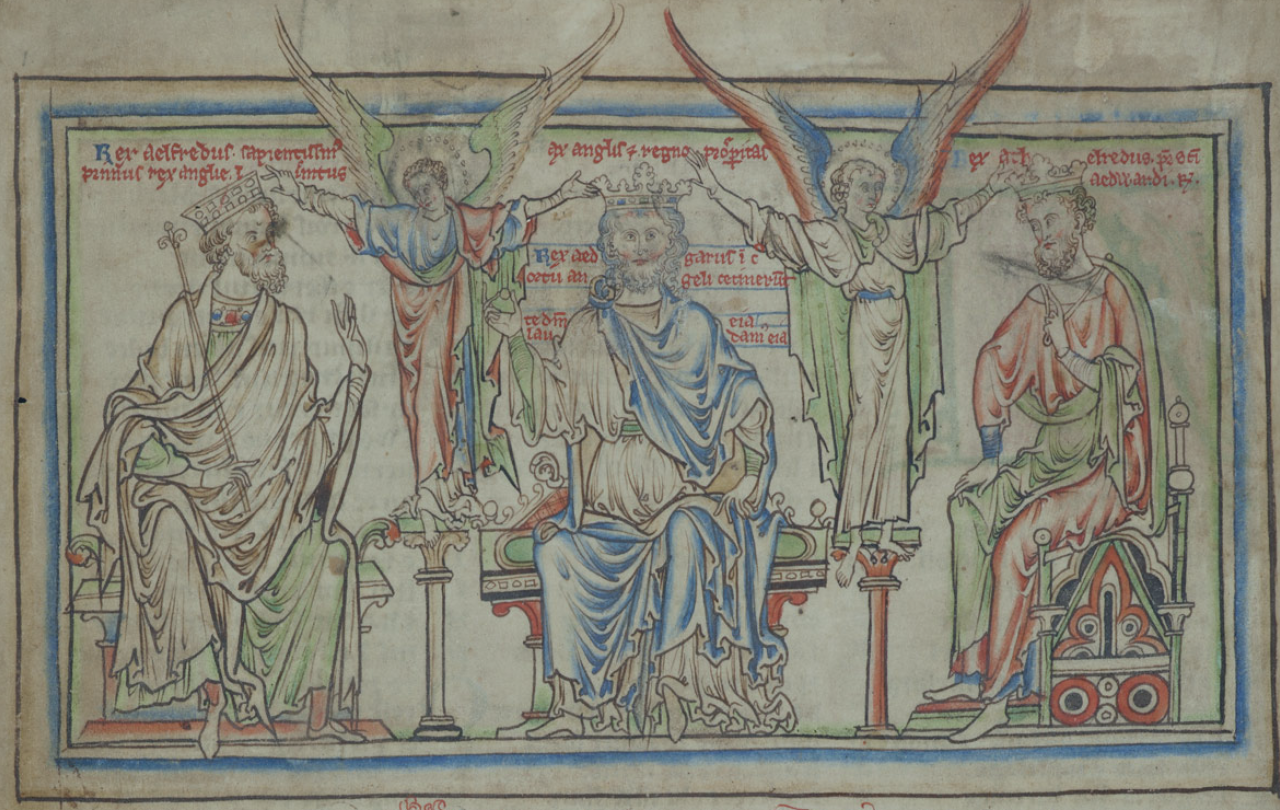

Coronations are religious services rather than constitutional ceremonies. While details have been subtly adapted over the centuries, the basic format has essentially remained the same for over a thousand years. The crowning of the monarch is just one of several distinct elements in the service. Others include recognition by the assembled congregation representing the people of their new sovereign, administration of oaths, anointing with holy oil, investiture with the royal regalia and celebration of Holy Communion. All these elements are present in the earliest surviving order for the coronation of an English monarch, prepared by St Dunstan as Archbishop of Canterbury for the Anglo-Saxon King Edgar in 973.

Edgar’s coronation, which took place in Bath Abbey, included many features found in all subsequent coronations. Held on Whit Sunday, the traditional day for ordinations to the priesthood, it laid considerable emphasis on the theme of consecration and the priestly aspects of kingship, exemplified by the wearing of priestly robes. Anointed and crowned by Dunstan, Edgar was entrusted with the protection and supervision of the church and graced with the titles rex dei gratia (king by the grace of God) and vicarus dei (Vicar of God). His wife, Aelfthryth, was anointed and crowned as queen. This practice, of a double crowning and anointing, was followed in the coronations of all subsequent married kings and queens as it will be with Charles and Camilla on 6 May.

Oaths and oil

Edgar was led into Bath Abbey by two bishops, as Charles will be as he enters Westminster Abbey which has been used for all English coronations since 1066. Before crowning, he was required to swear three oaths which form the basis of those still taken by every British monarch. As now framed, they include promises to adhere to the rule of law and the principles of justice and mercy, and to maintain the laws of God, the Protestant religion and the Church of England. Having taken the oaths, the monarch is anointed with holy oil, a further sign of being set apart and consecrated in the manner of a priest.

Earning the right

Edgar’s coronation included the celebration of Mass and it remains the case that the coronation is embedded in a celebration of Holy Communion. Dunstan’s order clearly established the church’s control over royal inauguration rites in England and specifically the key role of the Archbishop of Canterbury in presiding over the ceremony. In the sermon that he preached at a second coronation over which he presided, that of Ethelred the Unready at Kingston Upon Thames in 979, he preached on the duties of a consecrated king, describing him as the shepherd over his people and reminding him that while ruling justly would earn him ‘worship in this world’ as well as God's mercy, any departure from his duties would lead to punishment at Doomsday.

A sense of sharing

Rooted in tradition as they are, coronations still have the power to connect with the popular spiritual and religious instincts that remain strong, if often hidden, in our so-called post-Christian society. In a much-quoted article on Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation in 1953 two sociologists, Edward Shils and Michael Young, described it as:

‘the ceremonial occasion for the affirmation of the moral values by which the society lives. It was an act of national communion and an intensive contact with the sacred.’

They noted that it was frequently spoken of as an ‘inspiration’ and a ‘re-dedication of the nation’. The ceremony had ‘touched the sense of the sacred’ in the population, heightening a sense of solidarity in both families and communities. They pointed to examples of reconciliation between long-feuding neighbours and family members brought about by the shared experience of watching the ceremony together on television.

We have recently witnessed something of this sense of national communion and intensive contact with the sacred in the public reaction to the death of Elizabeth II, as shown by the numbers who came out to witness the progress of the late queen’s coffin on its last journeys and to file past it in the High Kirk of St Giles in Edinburgh and Westminster Hall.

Ultimately, Christian monarchy points beyond itself to the majesty, mystery and vulnerability of God. It is a lonely, noble and sacrificial calling. What our sovereign needs and deserves most is our loyal and heartfelt prayers. As we prepare for the king’s coronation, we could do well to reflect on and respond to the request that his mother made before hers:

“You will be keeping it as a holiday; but I want to ask you all, whatever your religion maybe, to pray for me on that day, to pray that God may give me wisdom and strength to carry out the solemn promises I shall be making, and that I may faithfully serve them and you, all the days of my life.”