This year marks four decades since the release of Bill Forsyth’s masterpiece, and it is a real joy to have the excuse to revisit it. Local Hero is a glorious warm-mug-of-tea of a film: charming, gentle, sweet, gorgeous, and funny in the kindest and most uplifting way. What’s more, its theme and message are as pertinent as they were forty years ago… more so, actually.

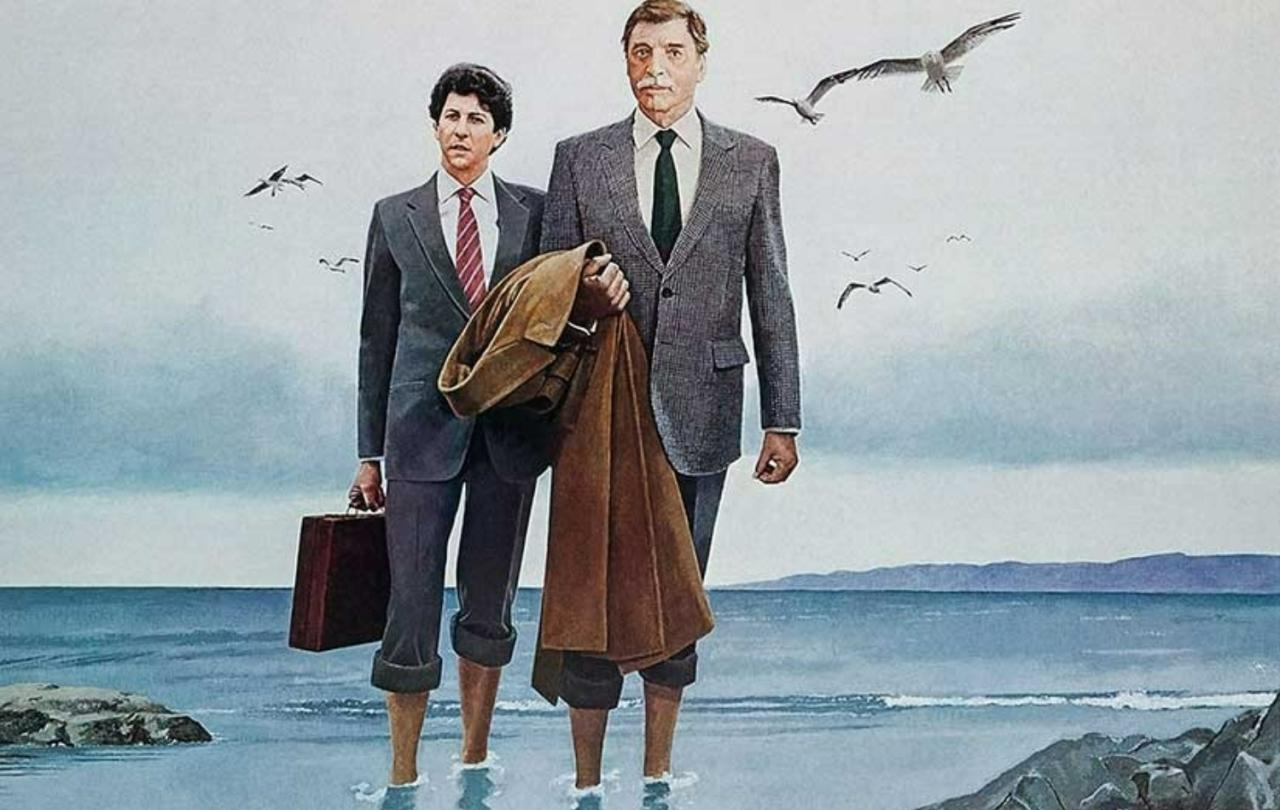

Local Hero follows Peter Riegert’s Mac, a faux-Scotsman who is displaced from his busy life as an oil executive in Houston to the small Highland village of Ferness. There he is expected to oversee the sale of the village and beach so it can be developed into an oil refinery. The eccentric and astronomy obsessed owner of the oil-company Felix Happer, played by Burt Lancaster, thinks that Mac is just the right man for the job on account of his name sounding Scottish.

Watch the Local Hero trailer

Upon arriving in Scotland Mac meets Danny Oldsen (Peter Capaldi) who will be his assistant from the Scottish branch of the company, and the two set off on the journey to Ferness – meeting Jenny Seagrove’s love interest and an ultimately unfortunate rabbit. When in Ferness Mac must contend with Denis Lawson’s hotelier-barman-accountant Gordon Urquhart, an affable but shrewd negotiator who is determined to get as much money as possible for the people of Ferness. During his stay Mac is baffled, bemused, and slowly bewitched by the colourful locals, from Urquhart’s wife Stella to Soviet fisherman Victor to shabby beachcomber Ben.

I dare not say much more about the plot so as not to rob you, dear potential viewer, of the delightful experience of allowing Forsyth’s perfect writing and delicate directing envelop and clam you, take you by the hand and lead you through the story with grace and wit. The performances are lovely, Mark Knopfler’s haunting soundtrack (a balancing of folk, soft-rock, jazz, and electronica) complements the scenery, and the BAFTA nominated cinematography by Chris Menges captures that wild and rugged coastal landscape in all its glory. The Scottish landscape is really the unspoken lead of the film, and more often than not transports the viewer into the transcendent realms of the sublime!

I chose my words carefully: the theme of the film is very much about the power of natural beauty to change the values and perspective of the individual. Mac begins the story as a high-powered and cynical corporate man – willing to lie about his name and preferring to do deals over Telex than have real human interaction with clients. Oldsen is young and ambitious, fascinated by the glamorous lifestyle of the US, and keen to do well in his chosen profession. Yet over the days and weeks that they spend in Ferness, their outlook begins to change.

What is wonderful about Bill Forsyth’s subtle storytelling is that we know all this not because of any grand speeches, but with little visual cues.

The sheer beauty and simplicity of the coast takes hold of the businessmen and overwhelms their ambition and materialism with the power of the sublime. What is wonderful about Bill Forsyth’s subtle storytelling is that we know all this not because of any grand speeches, but with little visual cues. Slowly the dress of the two men devolves to mirror their thoughts and feelings: from the full corporate dress, to the removing of a tie, to by the end of the film dressing like a local in a proper cable-knit sweater. Mac comes to see that emptiness and vacuity of his life in Texas and yearns for the simple life by the sea surrounded by the majestic Scottish cliffs. Even as the locals become more and more excited by the prospect of their newly promised wealth, Mac and Oldsen come to regret their involvement in a scheme that will destroy the glory of the landscape.

There is a message beneath the message: the sublimity of the natural world can only be truly experienced in the context of human relationships.

This in itself would be enough for the film to have maintained its relevance for forty years – it's impossible to study current affairs today without encountering worries about climate change, pollution, over-industrialisation, and the loss of the natural world. The film’s clear conservationist message is as fresh as ever, but it isn’t the most powerful, for there is a message beneath the message: the sublimity of the natural world can only be truly experienced in the context of human relationships.

As I watched the film again, I noticed that the power of the scenery in the background is complimented and elevated by the human connections in the foreground. Mac forges a real friendship with Urquhart and develops a real fondness for the local people, so although he loves the landscape it is the relationships it inspires that really move his heart. Oldsen may be wowed by the sea, but this is elevated by the love he feels for the mysterious, web-towed marine biologist Marina swimming in it.

The great irony of the story is that Mac and Oldsen – isolated corporate men – come to want to protect the integrity of the landscape, while Urquhart and villagers are motivated to sell and abandon it as the local economy stalls. They have grown up with the scenery, they have been formed by it, it is in their bones, and they have been blessed by the cast-iron community bonds that such sublime surroundings inspire; it is on account of their total lack of individualism or atomisation that they have the confidence to leave the community behind.

In the end, it is a fledgling relationship that saves the village. Happer, isolated and lonely at the top of the corporate ladder (so much so that he pays for his quack-psychiatrist to insult and berate him in the hopes of some emotional breakthrough – laugh-out-loud interludes in the storytelling), travels to Ferness himself to close the deal. Negotiations have stalled when Ben the beachcomber refuses to sell his stake in the village, quite an important stake…the beach itself.

Star obsessed Happer arrives convinced that he can talk Ben round, but rather than a negotiation the interaction becomes a meeting of minds in which Ben convinces Happer that the beauty of the stars is a far better investment than oil. Ferness WILL BE SOLD, but so as to be an unspoiled spot where an astronomy observatory can be built. The unlikely relationship that blossoms between and billionare oil-baron and a bumbling beachcomber saves the landscape and the relationships which Mac has come to love so dearly.

In a world where technology and social media continue to atomise and divide us, while at the same time giving us simulated experiences and the simulacra of friendship, Local Hero is a gorgeous and glorious antidote. It reminds us of the vital importance and power of human relationships, the pinnacle of our experiences which even mediate the sublime power of Scottish coastal scenery. An important message, and if I may, a comfortably Christian message: for relationship is at the core of who God is as Trinity, relationship is at the core of what God wants as he creates the world to be in communion with him, and relationship is at the core of how God brings about our salvation as he comes to us in the person of Jesus Christ who calls us his brothers and sisters and friends.

Whoever you are and wherever you are, you should watch Local Hero immediately and be reminded of the beautiful and the sublime power of the natural world, and most importantly of all, the beautiful and the sublime power of human relationships.