I heard them calling out to me as I walked down the street.

“Hey Paki, why don’t you go black to your own country?!”

I carried on walking. I was 14 years old, and I had heard it all before. In fact, I couldn’t remember a day when I didn’t face a similar verbal barrage at some point. It didn’t get any easier. It always hurt.

When you are told something over and over again, you can start to believe it is true. But I wasn’t from Pakistan. None of my family members were from Pakistan. I had been born in the Sussex County Hospital in Brighton. I had a British passport – as did my parents.

That group of people on the other side of the road were making judgments about me that were entirely wrong. I had to remind myself – like I did every day: they were the ones who were out of place, not me. They were the ridiculous ones, not me.

I flashback to that moment sometimes as immigration persists as a top news story. Most days in the media I hear someone say today’s equivalent of “Hey Paki, why don’t you go back to your own country?! The derision is there, the bigotry, the racism, the aim to exclude and to humiliate, the false assumptions and preconceptions.

It’s time to hear the other side of the story. Who are the refugees that are coming here? Why are they coming? What has happened to them to make them stay in a country that is not always as welcoming as it should be? How does it feel to be an asylum-seeker or refugee in the UK right now? For refugees who have faced not just verbal abuse but physical assault, threats of torture and death the very least we owe them is the courtesy of listening to their stories.

As we approach World Refugee Day on 20th June I would like to recommend you to spend some time listening not just to the polarising rhetoric but those about whom they are talking. The best way is to spend time in person with those who have been forced to flee their homes. The second-best way is to read books written by or about refugees. The following are some of the most powerful I have read recently:

The Lightless Sky by Gulwali Passarly

This beautifully written book will not only give you fresh insight into life in Afghanistan but will help you understand why there are unaccompanied asylum-seeking young Afghan boys in the UK. Gulwali explains his dangerous childhood in Afghanistan and why his family paid to have him taken out of the country. This book draws you into the world of a young boy proud of his heritage but fleeing a war zone that ripped his family apart. Gulwali’s journey takes him from the mountains of Afghanistan with his grandfather to a rollercoaster of a life in the UK and how he became a carrier of the Olympic torch and an outspoken advocate for refugee rights.

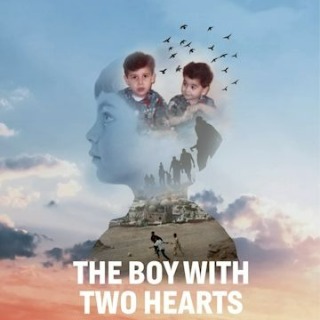

The Boy with Two Hearts by Hamed Amiri

I saw this gripping tale of Hamed and his family performed at the National Theatre in London. It begins with Hamed’s mother Fariba taking the brave decision to give a public speech against the injustices of the Taliban in Afghanistan. The Taliban issued an execution order against her which would likely have led to her death. The family sell their possessions and head out of Afghanistan to get anywhere they can to safety. There are added complications to their already challenging circumstances as Hussein, Hamed’s older brother needs urgent life-saving heart surgery. It’s a nail-biting story of love and loss told with grace as the family travel across seven countries to find sanctuary finally in Wales.

My Fourth Time, We Drowned by Sally Hayden

Sally Hayden did not plan to write a book about the world’s most dangerous migration route but when she received direct social media messages from refugees imprisoned in a Libyan detention centre her life was turned upside down. This gritty story has won numerous awards for outstanding journalism and opens up readers eyes to the desperate situation faced by asylum seekers in the Middle East and Europe. Sally writes with great precision and detail and offers a candid and challenging picture of life for those forced to flee from countries such as Sudan, Eritrea, Syria and Afghanistan.

You Don’t Know What War Is by Yeva Skalietska

Yeva Skalietska, aged 12, was sleeping soundly in her bed at her grandmother’s house when suddenly she was jolted awake by a noise that sounded like a car being crushed into scrap metal. She soon came to realise that a rocket attack was taking place in her home city of Kharkiv, Ukraine. Her gripping tale of those first few weeks of the Russian invasion told from a child’s perspective somehow brings home the reality of war in a most chilling and urgent way. It made me consider how my children would have dealt with all she had to go through.

No Place Like Home refugee book festival

If you would like to hear refugee authors such as the ones above telling their stories in person, the ‘No Place Like Home’ Literary Festival is taking place on World Refugee Day, 20th June, St Martin-in-the-Fields Church, Trafalgar Square. A full list of speakers, and tickets, subject to availability, can be found in this link.