Few White House Chiefs of Staff have been better than James A Baker III. Nicknamed the ‘Velvet Hammer,’ Baker was originally a Democrat, and only introduced to politics in his forties. But he made up for lost time, serving as the original catalyst behind President Ronald Reagan’s time in the Oval Office. He later served as Secretary of State, helping maintain peace following the Cold War.

In their recent biography of Baker, The Man Who Ran Washington, Peter Baker (no relation to James) and Susan Glasser write that, when called out of his retirement to lead the Republican strategy in the Bush-Gore 2000 Florida vote recount, ‘Baker’s reputation was so formidable that Democrats knew they would lose the moment they heard of his selection.’ More precisely, Baker ‘was not defined by his era; he helped to define it.’

And yet, the calm, cool and collected former Texas lawyer was – by the end of his tenure as White House Chief of Staff – broken. In Chris Whipple’s The Gatekeepers, a history of American White House Chiefs of Staff, a former Reagan staffer reflects that in a conversation long after their tenures, ‘Baker’s eyes filled with tears. He told me what it had been like for him to be chief of staff in a White House riven by different philosophies and ideological outlooks. And every day various people would try to take Jim Baker out.’

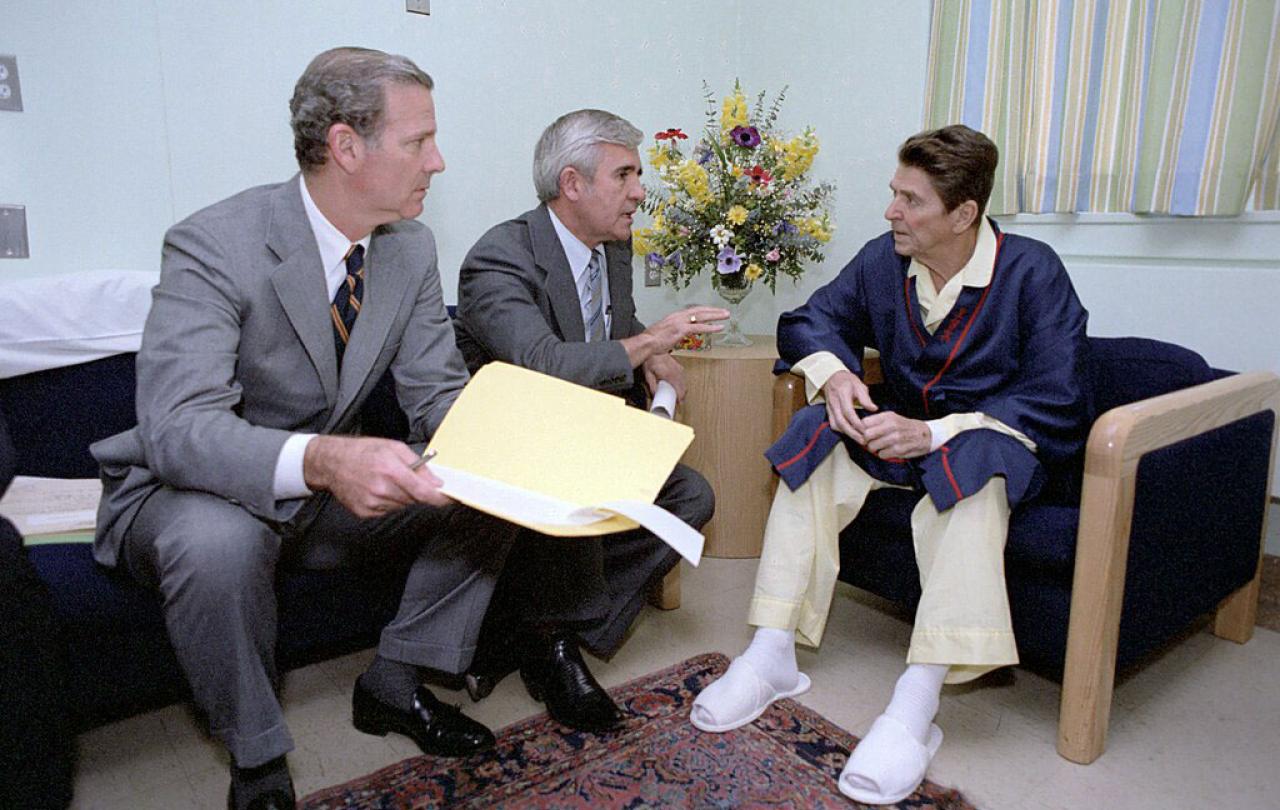

Baker, a problem-solver and political moderate, battled with his more ideological counterparts for the ‘soul’ of the Reagan presidency. This battle was ‘more emotionally grueling and deeply painful than almost anyone around him knew.’ His struggles were a harbinger of the more divisive American politics to come. Surrounded by long-time Reagan loyalists, he was an unexpected selection for the Chief of Staff role. He ran the Gerald Ford and George Bush presidential campaigns against Reagan but was recognised by the Reagans as the right person for the job. Baker kept focused within the Reagan Administration despite team members undermining him.

Baker shows that responding to a call requires that a person engage in the world as it is. This realism helps us to reform the world through service.

Through his participation in the world, Baker reminds us that life is messy. This is especially the case when engaging in communities involving competition between multiple worldviews, philosophies, or ideologies. Keeping the ship steady amid such variation comes with emotional cost. But participation is better than withdrawal from the scene of action, and into the safety of technology.

Balancing between perspectives requires a personal sense of restraint. Peter Baker and Glasser note, for instance, that ‘one of the keys to Baker’s success over the years was knowing when to back off’ in meetings. This balancing is difficult. Baker succeeded in his political vocation in part because he participated in this swirling mix of perspectives, but the balancing involved suffering.

What can we learn from Baker on the messiness of life? What does he show us about the living-out of a vocation? Baker was clear-eyed about his calling: that of serving his friend Reagan (and afterwards his close friend George Bush). He put his strategy and negotiating skills to good use as part of a larger life project. This calling strengthened Baker’s persistence, despite the trials and tribulations of participation in the world. Baker shows that responding to a call requires that a person engage in the world as it is. This realism helps us to reform the world through service.

‘Once we remove ourselves from the flow of physical, messy, untidy life… we become less willing to get out there and take a chance.’

How did Baker discover his political vocation? And what is a vocation? The philosopher Robert Adams defines vocation in his Finite and Infinite Goods as ‘a call from God, a command, or perhaps an invitation, addressed to a particular individual, to act and live in a certain way.’ The theologian Oliver O’Donovan defines vocation somewhat differently in his Finding and Seeking. He describes it as ‘the way in which the self is offered to us…. The course of our life that will come to be our unique historical reality.’ O’Donovan focuses on service, where vocation is ‘not a single function, but an ensemble of worldly relations and functions through which we are given, in particular, to serve God and realise our agency.’

Sometimes, as O’Donovan suggests, a calling captures our attention, even if we only know the immediate next step, as if stepping from a quayside onto a boat (a helpful metaphor used throughout O’Donovan’s work). For Baker, it was the death of his first wife that precipitated a call from his friend George Bush. In this conversation, Bush asked whether Baker would be interested in volunteering for a campaign, to help take his mind off his grief. What was initially a way to help keep his mind off a trauma became, over time, a life project.

Baker thought carefully about the world and the people around him as precursor to action. He epitomised the thinking of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who writes that individuals should participate ‘in the times and places which confront us with concrete problems, set us tasks and charge us with responsibility.’ We must remember that people are multidimensional. This is not easy, Baker as a case in point through his political vocation.

Unfortunately, while recognising this is a realm of considerable debate, aspects of our culture discourage genuine engagement in the world. Sherry Turkle, Professor of the Social Studies of Science and Technology at MIT, describes ‘networked life,’ where individuals use technological devices (we might think today of WhatsApp or Instagram) to withdraw from hard, in-person conversations. She says that people nowadays tend to communicate with others on their own terms. It is easy for people to engage – or disengage – others whenever convenient.

Yet, as Turkle writes, ‘Once we remove ourselves from the flow of physical, messy, untidy life… we become less willing to get out there and take a chance.’ Networked life is for Turkle an escape from the messiness of life. It prevents encountering others as they really are. This leads to weak personal foundations: personal characters built on sand rather than on rock. It helps to be tested by conflict with others that are different than ourselves. This testing helps to reduce narcissism, in which we think more about ourselves than about the wider world.

Marshall McLuhan, in his Understanding Media, reflects on the Greek word narcosis meaning numbness. The service of networked technologies, to which Turkle alludes, is in McLuhan’s eyes a worshipping of these technologies as God. This numbing via the worshipping of technology is contrary to Baker’s more engaged way of life – encountering others in person in their complexity.

We can remind ourselves that life is messy. What we think we see upon first impressions may evolve upon continuous examination. And what is previously unseen may become evident over time. Jesus states that ‘For nothing is hidden that will not be disclosed, nor is anything secret that will not become known and come to light’ and later, that ‘Nothing is covered up that will not be uncovered, and nothing secret that will not become known.’

The genius of James Baker was found not in academic intellect, but in his ability to understand others through real engagement in the world. This understanding of others, serving them, was the cornerstone of his vocation. Former White House speechwriter and now-columnist for the Wall Street Journal Peggy Noonan once commented – as reported in The Gatekeepers – that Baker ‘was a guy who didn’t seem to move forward with a lot of illusions about life or people or organizations or systems.’ Baker embraced the messiness of life, but also the importance of taking part to serve others and help restore the world.