Staying up late on a Friday night to watch Cheers was one of the regular highlights of my childhood. My parents were as bewitched as I was with the sonorous voice of Kelsey Grammer. Indeed, the whole world loved it. His spin-off sitcom Frasier went on to run for 11 years, winning 37 Emmy awards, a feat only recently surpassed by Game of Thrones. Grammer himself became one of the most decorated, well-loved – and well-paid - actors in the world.

Nearly 20 years after its final episode Frasier is being rebooted. This time it is returning to Boston, the place where everybody came to know Dr Frasier Crane’s name. I, like many, are jubilant, convinced that the warm, masterful and often farcical humour will resonate just as well with a new audience. But what about Grammer? How does he feel about putting on the jester’s motley and playing Dr Crane again?

“He's fantastic.”, Grammer explains to me with a broad smile and clear enthusiasm. I find myself wanting to tell him everything that’s keeping me awake at night.

“Whatever it is about this journey with Frasier: he's lived a kind of a parallel life with me. Now we've found our way back to one another.”

Grammer seems to be as excited as I am about the comedy comeback, but has Dr Frasier Crane changed over the decades? He explains:

“He's a little wiser, a little calmer about some things. He's still a bit of a nuts on others. But the growth of the last 20 years or so in his life is reflected, I think, in this performance now.”

Sometimes our greatest triumphs are accompanied by our lowest moments. At the same time that Frasier was first showering Grammer with fame, fortune and critical acclaim, he was wading through personal trauma. Substance abuse, addiction, and divorces resulted. I had to ask Grammer if he was a stronger person this time around:

“I came to this one differently. I came to this one prepared to enjoy it. The previous manifestation of Frasier was a little bit much maybe a little bit too soon. It was challenging at times.”

Grammer’s personal journey fascinates me. He seems to have resolved the sense of emptiness that so often accompanies great success. Perhaps a clue can be found in the film Grammer is in London to promote. Jesus Revolution is based on a true story from the 60s and centres on a small church in Florida which gets invaded by hippies. Grammer plays the role of Chuck Smith, the pastor who is torn between two very different congregations.

“He spoke to my sense of good. People finding themselves, finding their way forward and not giving up, not relenting. I loved his search and his courage in the face of a waning congregation and the challenge of trying to make God relevant in that time.”

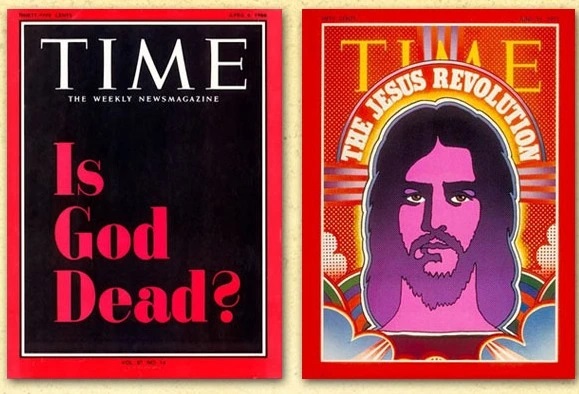

Time magazine covers from the 60s and 70s.

The film illustrates this challenge by bookending two editions of Time magazine. At the start of the film Grammer waves a 1966 cover at his sparse, stiff congregation. It is jet-black and asks pointedly “Is God Dead?” By the end of the film Grammer, surrounded by a crowd of unlikely long-haired worshippers, is clutching a Time Magazine from 1971, this time featuring on its cover a psychedelic picture of a bearded Christ proclaiming “The Jesus Revolution”.

Grammer’s character experiences his own personal Jesus revolution in the movie. He welcomes those long-haired bare-footed hippies into his home, his church, and his life, and as he begins to see the world – and God - through their eyes, he becomes a kinder, braver and happier person.

This is what I see in the Hollywood superstar I am interviewing: someone willing not only to talk openly about his faith, but to actively promote it. He is a man on a mission as he tells me:

"You can defend and champion and be an activist for a sort of alternate lifestyle or any number of things that you think are important. I applaud that. But it's also okay to applaud and champion the idea that a life of faith has equal value…”

Grammer, now wistful and warmer, adds:

"I just thought, I want to do something that has value, meaning, you know, other than just making people laugh."

Grammer grew up in a family of faith, but that family was also torn apart by heartbreak. His father was brutally murdered when he was just 13 years old. Seven years later his sister was abducted, raped, stabbed and left to die in a trailer park. I ask Grammer bluntly how he can have faith in God after such horrors and suffering:

“Well, I've been wrestling with it my whole life, since the early days of when tragedy first came knocking at the door… And I spent a long time looking around, you know, thinking, what the heck happened? Very recently, I stood on a baseball field at one of the harvest revivals and I just said, “Where were you?”. He said, “I was right there.”

Grammer has found a way to make sense of his life, a way to deal with trauma and tragedy. Like Chuck Smith making room for the outcasts, like Dr Frasier Crane making time to listen to troubled people on the radio, Grammer could be a new sort of pastor for a new generation.

“I think people are walking around with broken hearts. I hope they have a chance to say: ‘Well, maybe, maybe this faith thing isn't so bad.’”

Maybe he’s right. For a man that has experienced more than his fair share of personal tragedy, I have the feeling that he knows what he’s talking about. I came away feeling moved by his continuing faith in God despite everything he has suffered and despite everything he has struggled with. I hope audiences will see something of that authenticity and challenge in Jesus Revolution.

Jesus Revolution is on UK and Irish cinema release. Tickets are available now.