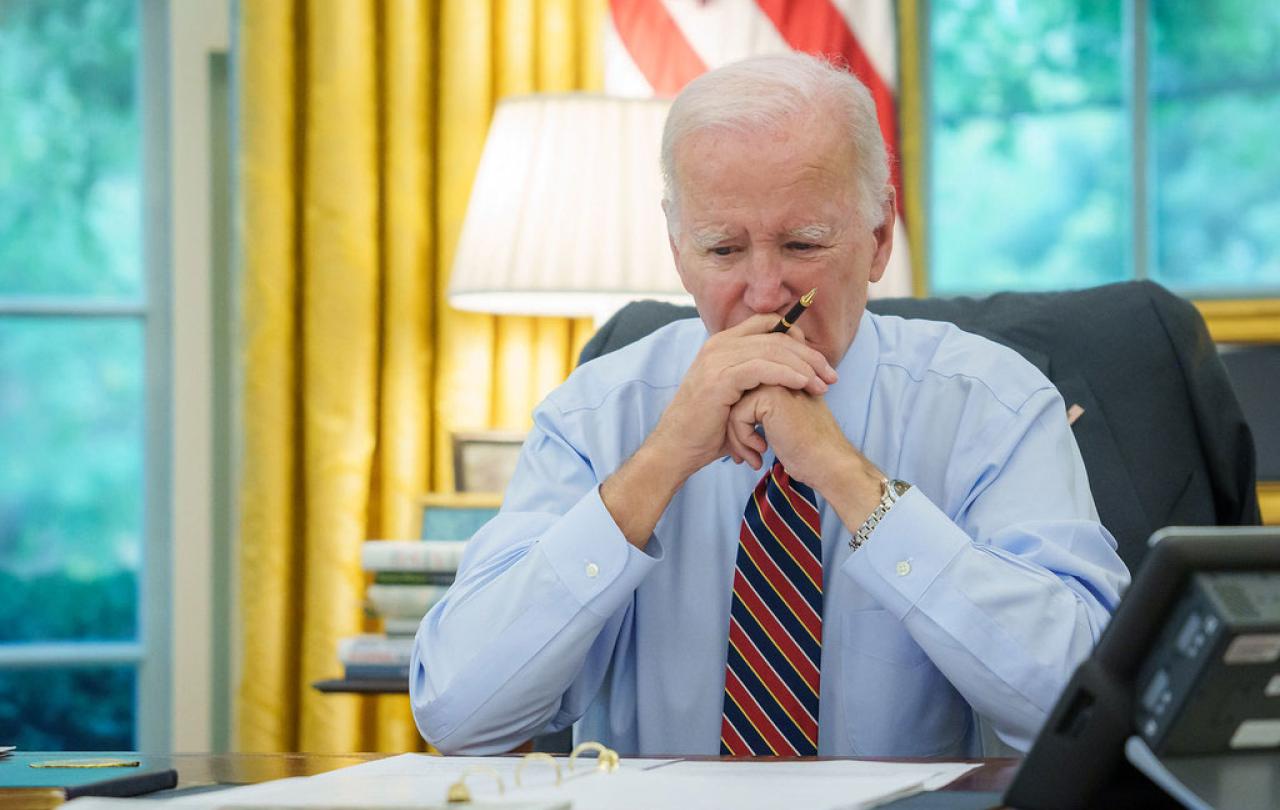

I am the same age as President Biden. So part of my heart went out to him as I watched his catastrophic confrontation with Donald Trump last week.

As we octogenarians know, or should know, our physical and mental faculties simply don’t work as well as they used to. If tested in the white heat of a Presidential debate, or at a multitude of far lower-level challenges, it is all too easy to slip, stumble or fall.

These human weaknesses have been almost unchanged for time immemorial. They were painfully if poignantly expressed some 2,500 years ago in the Psalms of David:

“The days of our age are threescore years and ten; and though men be so strong that they come to fourscore years: yet is their strength then but labour and sorrow; so soon passeth it away, and we are gone.”

Modern optimists may try to argue with the ancient psalmist. In our 21st century era of vitamin pills, workouts in the gym, macrobiotic diets and intermittent fasting, we are all too willing to believe that we can postpone the arrival of the grim reaper or at least prolong our youthful vitality.

Politicians are particularly susceptible to the fantasy that they can stay on their best form into old age longer than anyone else. “Age shall not weary us” they whisper to themselves, citing elderly successes such as Winston Churchill who became Prime Minister in 1940 aged 67, leaving Downing Street at the age of 80; William Gladstone who formed his last administration when he was 82; or Ronald Reagan who rode off into the sunset aged 77.

There are many reasons why political leaders have a tendency to hold on to power beyond their sell by date. Their egos make them believe they are indispensable. Their courtiers, their staff and their appointees like to stay in power too. When the White House changes hands approximately 30,000 people lose their jobs, from mighty Cabinet Secretaries in Washington to humble rural postmasters in Hicksville. So there is a built-in bias for preserving the status quo, by fair means or by flattery.

What President Biden now needs is loving, personal advice from his nearest and dearest, and wise political advice from disinterested friends whose candour he really trusts. Will he get it?

My late wife, Elizabeth, was brave in giving what she called “frank notes” to all three of her husbands when she watched them perform on stage, on screen, or, in my case, in pulpits.

Her movie star spouses, Rex Harrison and Richard Harris, were not always pleased when her notes criticised them for forgetting their lines, failing to sound consonants, or dropping their voices at the end of sentences. I, too, was sometimes less than appreciative, but I always took Elizabeth’s advice. Would that Jill Biden might now imitate such similar Elizabethan candour.

In his perceptive article on this subject for Seen & Unseen, young Bishop Graham Tomlin (he’s about 20 years younger than me!) made excellent points about the calling of old age. To which I can cheerfully shout, as if I was still in the House of Commons: “Hear! Hear!”

For, since being ordained at 74, I have found enormous fulfilment in the calling of prison chaplaincy, pastoral care, and preaching. These are not to be compared to the fastest tracks in competitive careers like politicians or investment bankers. Yet they have brought me great joy and I hope they have sometimes helped my prisoners and parishioners.

The race is not always to be swift.