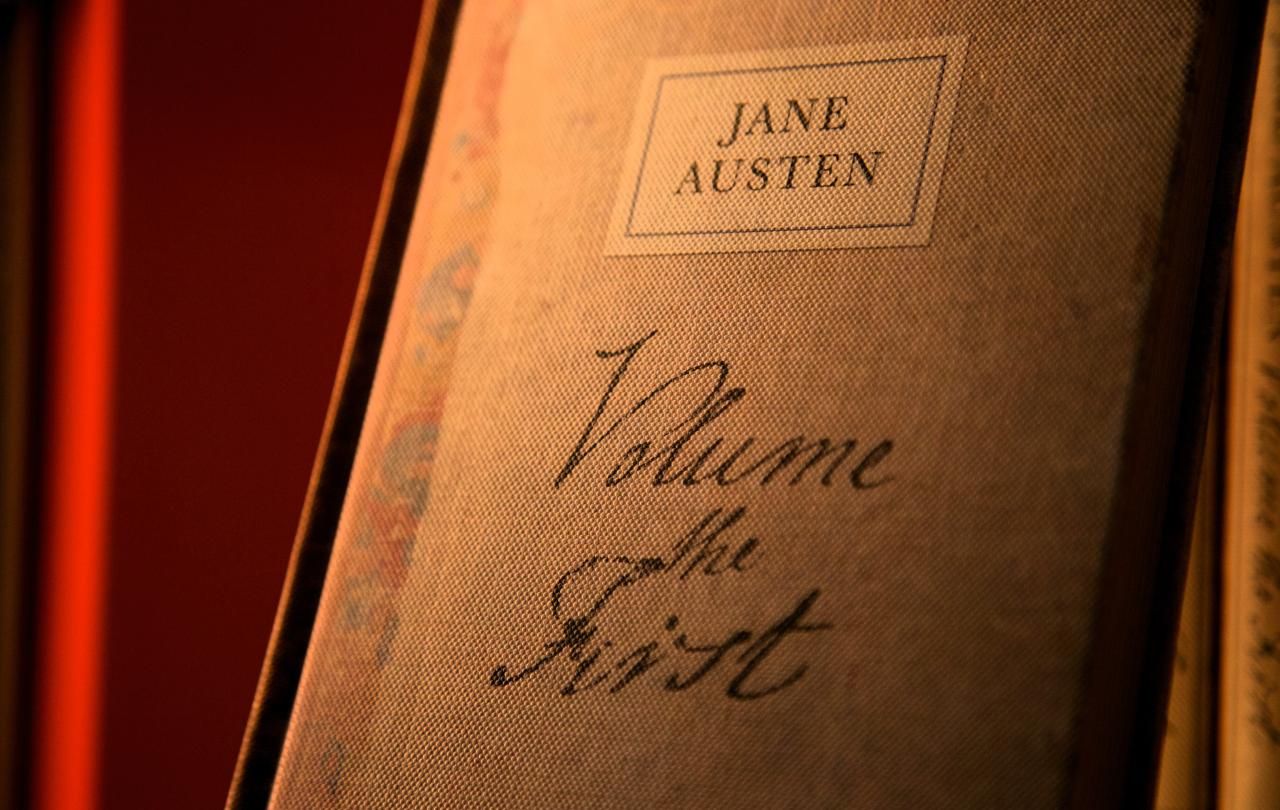

250 years after Jane Austen’s birth, her stories are still an incredibly significant part of our culture. The annual Jane Austen Festival in Bath is gearing up to be bigger than ever; Winchester Cathedral is set to unveil a new statue of Austen later this year; and – perhaps most controversially – Netflix has announced yet another adaptation of Pride and Prejudice.

Historically, there’s been an overwhelming focus on two elements of Austen’s writing: the Regency setting, and the romance plots. There’s nothing inherently wrong with enjoying these two aspects of her novels. I know I do. But this comes at the risk of underestimating the richness of Austen’s literary legacy. The internet is littered with listicles and blog posts in the format of ‘What to Read Next If You Love Jane Austen.’ Some of these lists will point you to other nineteenth-century literary classics. Others will home in on the romance element, recommending Helen Fielding’s wildly successful Bridget Jones’s Diary, Georgette Heyer’s Regency romances, or even Julia Quinn’s Bridgerton series.

I’d like to share with you an alternative and more eclectic list of books that I’ve fallen in love with as a lifelong Austen fan. Only one of these books is set in the Regency era; some have a romance as a major part of the plot, others don’t; some share Austen’s realistic writing style, one borders on magical realism. But I think each of these novels or authors brings out a fascinating and often overlooked aspect of Austen’s literary inheritance.

Anne Brontë’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848)

Austen is regularly compared to Charlotte Brontë, who famously wrote Jane Eyre, but I think her younger sister Anne is a fairer comparison. Writing only a few decades after Austen’s death in 1817, Brontë’s style is closer to Austen’s realism than to her own sister Charlotte’s use of gothic tropes and supernatural themes. Like Austen, in The Tenant of Wildfell Hall – as well as in her other novel, Agnes Grey – she focuses on simple language and engaging dialogue. Austen and Brontë also share a deep concern for female education. In several of her novels, notably Pride and Prejudice and Emma, Austen critiques the reality that many young women from middle-class and upper-class families were being taught to value ‘accomplishments’ like dancing and singing over any other form of education, with the aim of attracting a rich husband. Similarly, in The Tenant of Wildfell Hall Brontë’s heroine Helen criticises society’s belief that boys and girls should be educated differently, with boys being taught about the dangers and vices of the world, and girls being kept in ignorance of them. Helen thinks that this attitude makes girls more vulnerable to suffering and disappointment; I suspect Austen would have agreed.

Barbara Pym’s Excellent Women (1952)

Now somewhat forgotten, many of Pym’s stories are considered ‘novels of manners’, that is, novels that detail the costumes and values of a particular sphere of society at a particular time in history: in Austen’s case, the middle and upper classes in Regency England; in Pym’s case, the parishioners of a typical Anglican community in post-World War II London. Like Austen, Pym’s writing style is incredibly witty, and both writers favour everyday stories about ordinary people. In fact, Pym took the title Excellent Women from a phrase used by Austen in her unfinished novel Sanditon. These so-called ‘excellent women’ perform seemingly unheroic, small duties for others, the kind that may well go unnoticed, but which are often indispensable in small communities. In Pym’s novel, the first-person narrator, Mildred Lathbury, spends her life between working at a charitable organisation and helping and helping the priest at her local Anglican church. Mildred’s work is often taken for granted, much like the heroine of Austen’s Persuasion, Anne Eliot, whose family are remarkably ungrateful for all the ways in which she eases their burdens. Novels like Pym’s rightly celebrate the quiet bravery of the women who devote their lives to serving others.

P. D. James’ Death Comes to Pemberley (2011)

Detective fiction is not the first thing that crosses my mind when I think about Jane Austen. And yet, in a 1998 talk to the Jane Austen Society titled ‘Emma Considered as a Detective Story’, novelist P. D. James made a compelling case that Austen should be considered a precursor to the genre. James argued that a detective novel isn’t defined by the discovery of a murder (nobody dies in Dorothy Sayers’ acclaimed Gaudy Night, for example), but by the unveiling of a mystery. In Emma, Austen scatters clues for us readers along the way but withholds enough information as to keep us – and Emma herself – in the dark. When it’s revealed that Jane Fairfax and Frank Churchill have been lying to hide their secret engagement for the entirety of the novel’s timeline, Emma realises how much she’s been deceived, and it’s this theme of deception that really links Austen’s novel to the detective genre. Yeas after her talk, James ended up writing a detective fiction sequel to a different Austen novel, Pride and Prejudice. Death Comes to Pemberley takes place six years after Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy’s wedding. A man is found dead on the grounds of Pemberley and Mr. Wickham is the prime suspect. I won’t say any more. It’s my favourite retelling of an Austen novel.

Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant (2015)

The Buried Giant tells the tale of a Briton couple, Axl and Beatrice, as they set out on a quest to find their long-lost son in a post-Arthurian England where people struggle with the loss of long-term memories. Ishiguro blends a very realistic portrayal of the relationship between a married couple with magical elements such as the presence of a dragon whose breath causes forgetfulness. On paper, this is also not an obvious recommendation, yet memory is a crucial theme for Austen. Persuasion is centred around Anne Eliot’s memories of her broken engagement to Captain Wentworth, which simultaneously bring her happiness and suffering. Mansfield Park’s heroine, Fanny Price, has an equally complex relationship with her past. She often she misses her childhood home, yet part of her is glad that she was taken to be raised by the Bertram family at Mansfield Park, a place which she loves in spite of painful memories of being mistreated by her Aunt Norris. Fanny thinks of memory as the most wonderful faculty of human nature, as it can be at times incredibly ‘retentive’, at others ‘bewildered’ and beyond our control. Ishiguro would surely agree, as that’s precisely what The Buried Giant is about: the ways in which memory can both fail us and yet give us hope, recall suffering and yet brings us closer to those we love.

It’s hard to overestimate Austen’s impact on the literary world. And while she’s sparked a revival in literature set in the Regency era, it’s also fascinating to see how she’s influenced writers working in seemingly very different genres from her. Anne Brontë’s novels may be darker in tone, but they show very similar concerns to Austen’s, especially when it comes to virtue and education. Barbara Pym wrote Excellent Women over a century after Austen’s death, yet shared Austen’s interest in highlighting the joys and sorrows of ordinary life. P. D. James found inspiration in Austen despite her own background being in detective fiction. And Ishiguro, despite writing novels ranging from dystopian science fiction to magical realism, has mentioned Austen as an inspiration.

If you’ve already read all of Austen’s novels, read them again – no one writes quite like her. But once you’ve reread them all, why not try one of these novels next? They may illuminate a side of Austen’s writing that you’ve missed before.

Join us: support Seen & Unseen

Since Spring 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,000 articles. All for free.

This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief