William Blake once warned:

I was angry with my friend;

I told my wrath, my wrath did end.

I was angry with my foe:

I told it not, my wrath did grow.

Blake understood that unspoken—and, more precisely, unheard—wrath does not wither. Left untended, it grows. Its bitter roots tentacle around grievance; neglect waters it, and violence ripens as its fruit. Much like Blake’s tree, the wrath spreading through towns in this nation, and beyond, springs from seeds of anger. It is not irrational. It is cultivated in betrayal, frustration, and systemic disregard.

This essay is a triptych. Three panels, three faces of wrath poorly heard and poorly expressed. In England, it riots in the streets and hangs from lamp posts. In America, it narrows into bullets. These are not isolated curiosities but variations on the same Western fracture — anger left unheard, curdling until it explodes.

Wrath, of course, is not the same as anger. Anger is a natural passion, a flare of the soul in the face of injury or injustice. It can be righteous when governed by love, as even Christ was angry at hardened hearts. Wrath, by contrast, is anger left to harden — anger unspoken, unheard, or indulged until it festers into a vice. Scripture names it as both the fire of God’s judgement and, in humanity, a deadly sin. Wrath is anger that has ceased to heal and has become scar tissue.

Panel I: Gary from Blackpool

Enter “Gary from Blackpool”.

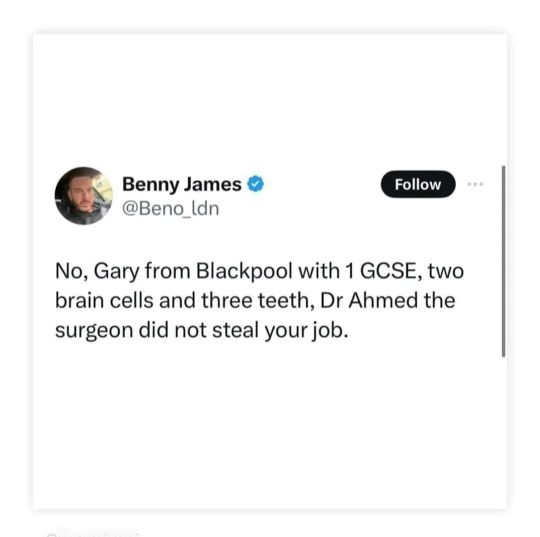

He was a London commentator’s caricature of provincial ignorance—“1 GCSE, two brain cells, and three teeth.”

The tweet was deleted, but not before the sneer had spread. Gary was a meme. He doesn’t exist, and yet he does; there are loads of “Garys” in Blackpool.

And Gary is angry.

His wrath first erupted in St John’s Square in the summer of 2024. When he raised a St George’s flag on a roundabout, it was not swaggering nationalism but a pathetic attempt to claim a place in a nation that no longer cares about people like him.

Blackpool’s collapse has been much-storied: once thriving, now one of the most deprived. Reports and documentaries measure poverty, chart prospects, and speculate on futures. The town is endlessly narrated.

Gary is not.

Yet his story mirrors that oft-told collapse. Poverty has scarred him visibly: the teeth, failing health. Gary’s life expectancy: 69, more than a decade shorter than elsewhere. He’s scarred invisibly too, in narrowed hopes and disillusion. These are not individual failings but markers of systemic neglect: underfunded schools, crumbling services, an NHS that doesn’t reach him. Dentist appointments in Blackpool are rarer than hens’ teeth, which are in better condition than Gary’s.

The England Gary remembers is gone. In its place stands a society he no longer recognises: multicultural, politically sensitive, shifting away from its past. A Daily Mail headline once told him, “Garys are heading for extinction” while Muhammad, in all its spelling variants, had become the most common baby name.

And then the boats. Images looping on his screen: more change he cannot control. His Brexit vote promised to take back control; his refusal to vote ever again, a gesture of resignation.

Because they don’t care about him. They hadn’t even cared for the girls. Now he saw the same system ushering them into clinics to become boys.

Gary and those like him, through their anger, reveal a politics that has abandoned them, economics that offer no hope, and a culture that makes them strangers in their own country. Rioting is no cure; it tears open wounds without healing. But the response is illuminating: in 2011, they prompted soul-searching; in 2024 and 2025, they brought only ridicule. The tweet exposed a national reflex: to mock rather than listen. That sharpened the bitterness.

Wrath here does not whisper or wait. It riots.

Panel II: Charlie Kirk

Gary may never have heard of Charlie Kirk, but Kirk’s rhetoric channelled the very anxieties that defined Gary’s world—about loss, displacement, and neglect. This resonance helps explain how his voice travelled so widely.

I didn’t watch Charlie Kirk either. His reels surfaced on Instagram or YouTube now and then, but it wasn’t my algorithm that latched onto him. It was my four nephews’—aged sixteen to twenty-two, two in Kent, two in New Zealand—imagination he captured, even if not always their agreement. Young men across the globe, caught in the fast cadence of an American voice.

When I saw the news, my reaction surprised me. It was strangely visceral for someone who had never featured in my life in the way he had theirs. I felt sick. Because he was dead. Because he wasn’t a politician behind glass or a general behind medals. He was public, certainly, but also strangely normal. And he had children, both younger than my youngest, and a wife.

And he had the guts to speak to people. Theo Von said he “tweeted with his feet.” How many of us can say we say what we believe as vociferously face to face as we might be brave enough to do on social media? He was visible. Accessible. Flesh and blood with people, not just pixels. I think this is partly why he appealed to my nephews. I’ve seen Facebook friends of their generation posting tributes, then engaging courteously and constructively with those who insisted on quoting Kirk out of context. For them, defending him has not been rage but dialogue.

And then the gun.

Charlie’s killer pulled a trigger. Wrath had narrowed into single, precise bullets with slogans on them. But this was not justice, not even protest. It was wrath corrupted into murder; an execution.

Wrath here does not riot. It narrows into bullets. It turns cannibal.

What will this spilt blood birth in those who listened, watched, believed?

Panel III: Flags in Hartlepool and Horden

And here, in England, it is the flags.

In America, flags are furniture. They’re on every porch, every school, every stadium. But in Hartlepool and Horden, when flags multiply on streetlights, and red crosses are painted onto white roundabouts, they do not feel ordinary. They are a display of patriotism that feels out of character here. They feel ominous.

They do not shout; they whisper. Every day. A slow, stubborn signal of belonging and defiance. Not the riot of Gary. Not the bullet for Charlie. But something quieter, somehow more enduring. Wrath sewn into fabric, taking root in silence as surely as Blake’s tree, its persistence echoing Gary’s resentment, its quiet endurance unsettling in a way different from the bullets that struck Charlie. When they thicken in certain places, when they layer and cluster, they become atmosphere.

Union Flags made it onto some streetlights I walk past with my daughter in Newcastle, on the way to the swimming pool. “What do they mean?” she asked. For some, pride. For others, threat. For most, perhaps nothing at all. And then they were torn down, leaving a frayed seam, a dangling strip of tattered cloth still tied to the upright metal. That felt even more ominous. Not simply a sign of division, but of reaction. And do you notice, where they are hung only as high as a ladder will reach, they look almost like flags at half-mast? As if beneath the defiance there lingers a subconscious grief.

And so the question lingers: what will come of it all? What future is being staked out? Are these new buds on Blake’s poisonous tree?

Some flags are celebrated, raised over civic buildings as sacraments of a new national creed.

Other flags are torn down, left to fray on lamp-posts, almost threatening in their persistence.

Wrath here does not riot or narrow. It takes root.

This is England, isn’t it?

A benediction: I was angry

And how might anger, left unheard before it hardens into wrath, speak with the voice of Christ?

I was angry, and you called me gammon.

I was angry, and you called me woke.

I was angry, and you heard only your politics,

not my pain.

I was angry, and you argued about tribes and sides.

I was angry, and you measured me as vote, as threat, as cause.

I was angry, and you did not really listen to me.

Truly I tell you:

when you saw the angry and called them only left or right,

you understood nothing.

You did not know me.

And these will go away still unheard,

their wrath growing strong in the shadows, waiting to erupt.

But those who bore the anger of the poorly heard,

who listened without contempt or fear,

This too is England. I am found there.

This article was first published on John Clifton’s SubStack. It is reproduced by kind permission of the author.

Support Seen & Unseen

Since Spring 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,500 articles. All for free.

This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief