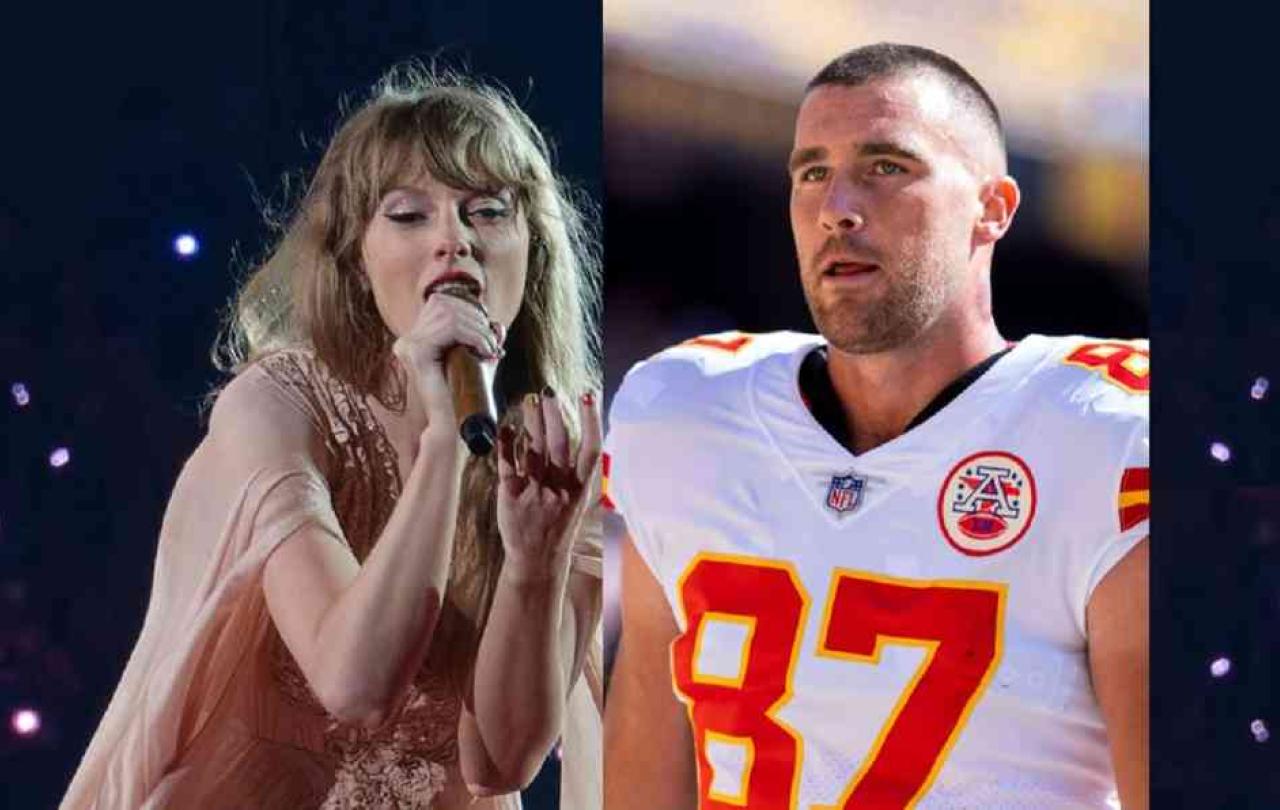

If you live on planet earth, you no doubt have heard of our now famous local love story: Kansas City Chiefs tight end player Travis Kelce is courting pop sensation Taylor Swift. One can read multiple accounts of this special love story on the Internet. (One of my favorites was written by London's The Guardian.) I don’t intend to repeat this well-known narrative. Rather, I wish to add commentary from what my wife calls a certified “Catholic Romantic”, or what my students call me, “a lover of human love.”

From the outset, please don’t get me wrong. I do not mean to canonize Taylor Swift or Travis Kelce or propose that their relationship is the ideal. I merely want to notice some very healthy things about it.

I tip my hand in the opening sentence. I describe the relationship as “courtship” not “dating.” Courtship differs from dating in terms of its intention, methods and goal. A man courts a woman whenever he pursues her seriously for a romantic relationship that is opened to the exclusiveness of marriage. The intent (serious) and goal (exclusive) determines the methods.

They met on common turf with uncommon talent. But she first made him work “for the right to party.”

After Ms. Swift declined Mr. Kelce’s unimaginative “I’m just a good ole boy” friendship bracelet, he decided to up his game – or better – run his own route. He invited Swift to return to Arrowhead Stadium to watch him “light up the stage” just as she had done three months earlier. She accepted this time. They met on common turf with uncommon talent. But she first made him work “for the right to party.”

Courtship requires work, which brings clarity to the relationship. Ends determine methods.

Another difference between courtship and dating is that it’s a family affair. Persons are more than individuals; we are social creatures who live, move and have our being in webs of relationships. We cannot know each other truly or deeply apart from those webs that create and sustain us. At the first two Chiefs games Ms. Swift attended, she was seen cheering alongside Mr. Kelce’s mom. After those central relationships have been honored, the widening circle of friends are introduced. And good friends know their role: circle the couples relationship and then face the crowd.

Kelce’s teammate Patrick Mahomes, as usual, threaded the needle, saying:

“She’s good people. Now let’s let them alone.”

What Kelce recently told reporters was refreshing. “It feels like I was on top of the world after the Super Bowl and right now I’m even more on top of the world,” he said. And when asked about having to navigate so much public interest in his relationship, he said, “You’ve got a lot of people who care about Taylor, and for good reason.” Excellent answer.

Finally, not all courtships end in marriage. And if this one doesn’t it is not a failure. If the couple loves each other well they will leave the relationship better for having known each other. Courtship is always a growth in self-knowledge by way of self-donation. They will grow as they learn to give of themselves. May they give of themselves and by so doing learn to make their love work.

As others have already said, this is the best catch of Travis Kelce’s life. And I, for one, hope he never lets her go.

This article was first published as: The Kelce Courtship of Taylor Swift, on the Benedict College web site.