Lent is upon us: the season to cultivate virtue. In that old-fashioned word, ‘virtue’ – so unpromising, even dismal in tone – lies so much of what Christianity wants to commend in its vision of a moral life. Even if Christian ethics enjoys a dour impression in the popular imagination, the tradition known as ‘virtue ethics’ places its emphasis on happiness, not being miserable, and on having a good disposition, not primarily on following laws. It’s all about having a good disposition – on being the sort of person to whom goodness comes naturally, even under taxing circumstances – and that as the basis for happiness. For the virtuous person, a virtuous response has become second nature: spontaneous, easy, and cheerful.

The idea of virtue as ‘second nature’ draws on Aristotle’s idea of habit. Over time, he thought, we settle into certain ways of being and reacting: into certain ways of behaving, responding, and relating to others. That can be for good, in which case we call that habit a virtue, but also for ill, in which case we call that a habit a vice.

'We are cultural, linguistic, and moral, and we have to learn and practice those things that make us human.'

We are creatures of habit, which makes us a strange sort of creature. We are born very much still a work in progress. All sorts of other organisms can perform their most characteristic actions more or less from birth. Contrast us. We are cultural, linguistic, and moral, and we have to learn and practice those things that make us human. In many important respects, what or who an infant will become remains an open question.

Aristotle put this pithily:

‘The virtues arise in us neither against nature, nor simply by nature. Rather, our very nature is to acquire them, and it is in that way that our nature reaches completion.’

Our nature is to be open, those works in progress. Inevitably, we acquire habits, one way or another, for better or worse. Habits are like a sediment that is laid down over time. Or – perhaps better – habits are like the course that river cuts through sediment or soil. The river cuts the course, but eventually the course directs the river. Acts lay down habits, then habits shape acts.

'We don’t become better or worse primarily by thinking hard about it; we become better or worse according to the way we act.'

That offers a bracing and distinctive view of what it means to be moral. For one thing, it shifts the emphasis away from motives, psychology, and an inner realm of the mind. We don’t become better or worse primarily by thinking hard about it; we become better or worse according to the way we act. Good deeds beget good habits, which beget further good deeds; bad deeds beget bad habits, which beget further bad deeds. That’s a good reason to make Lent a time for doing things (and maybe also not doing things, although virtue ethics will tend to think that action is important, and that we best drive out bad habits with good ones).

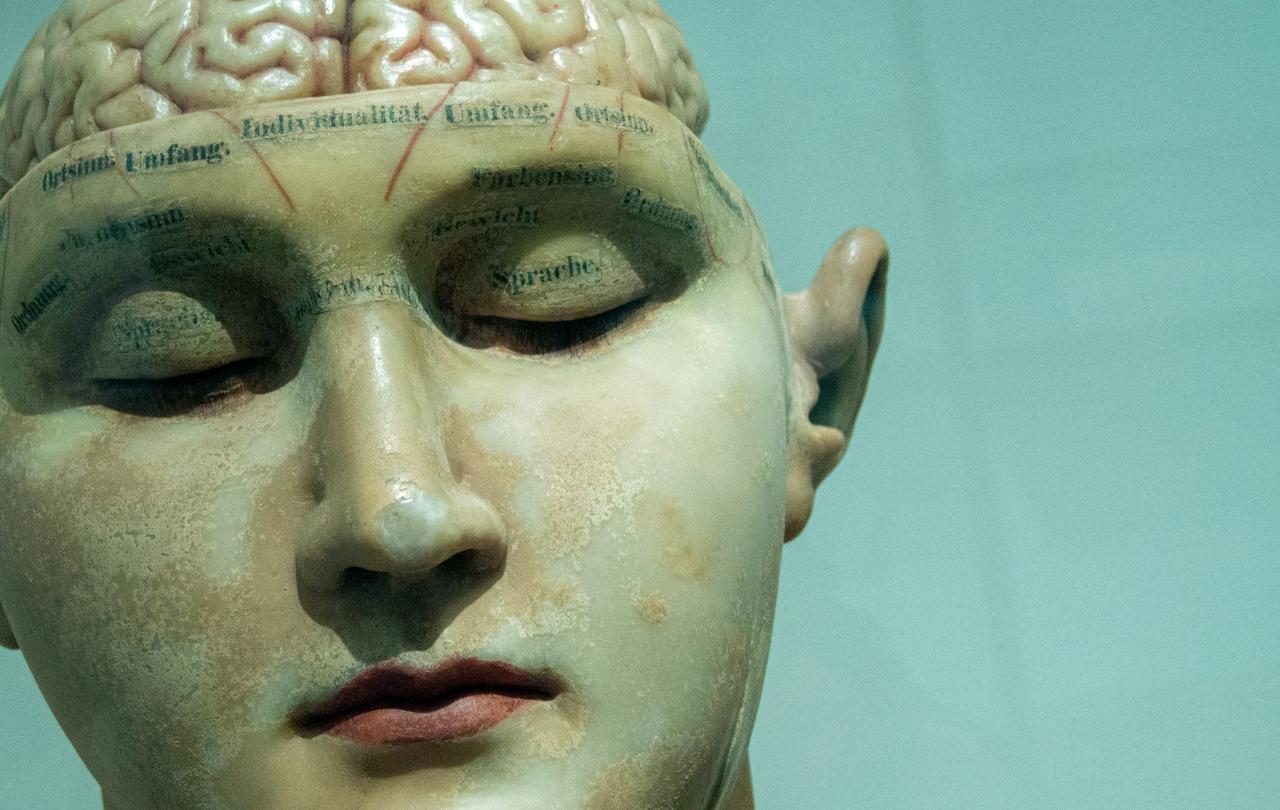

Virtue ethics has a lively place for reason, and we will come to that in the next article in this series (on the all-important rational virtue of prudence), but it’s also a remarkably bodily tradition. Virtue is almost as much laid down in one’s bones and sinews as in one’s brain. There is a ‘muscle memory’ to virtue, as also to vice. Imagine rescuing a child from an oncoming bus. It belongs to virtue in that situation for the body to move before the mind can catch up, or at least the conscious, deliberating mind. The child is snatched from danger in a pre-conscious whirl. The first well-formed thought to cross the mind of our virtuous protagonist might well be ‘Goodness, look what just happened?’

Virtue is at both home with dramatic responses in dramatic circumstances, but also disinclined to dramatize itself. The same person who reacted so bravely, and on instinct, faced with the child and the oncoming bus, is also likely to say ‘What else was I going to do? No big deal.’

The strength in virtue

The word virtue relates to the Latin with the word for strength. Virtue is strength of character. Virtue fills out what humanity can be. We might be born a work in progress, but that progress can go better or worse, depending on whether that human life is fulfilled in virtue, or hampered by vice. To fall into vices is to live an attenuated life, the glory of our humanity tarnished. To rise to virtue is to live a life of the kind of splendour of which a human being is capable.

Christianity has things to say about the crookedness of our tendency towards doing wrong, but rarely has it denied that we are still capable of making choices that are either better or worse, of performing better or worse actions, and of being formed, as a consequence, into better or worse people. Virtue isn’t the whole Christian story. It might not even be half the story, but it’s an indispensable part.

Offering common ground

Virtue perfects nature, as far as nature goes, but that isn’t the main part of that Christian story. It goes on to say that grace elevates humanity to a state beyond its wildest natural imaginings: to ‘participation in the divine nature’ and being a son or daughter of God. (There will be much more on all of that in other posts on this site). But, while that comment puts virtue in its place, it’s still an elevated place. If you are sympathetic to Christianity, but standing somewhat outside the door of the church, the traditions of thought and practice around virtue might offer common ground: common, both because they are about making the best of a humanity that we share, and common because so much of the thinking about them has been carried out across and beyond confessional lines, the great example being the place of Aristotle – an ancient Greek pagan – in all of this.

The virtues

Aristotle singled out four primary virtues. They are prudence (or practical wisdom), justice, courage, and moderation. To these, the church added three from St Paul: faith, hope, and love. We will think more about each of these in the weeks ahead, as we journey through Lent, and onto Easter.

Who is the honest man?

He that doth still and strongly good pursue;

To God, his neighbour, and himself, most true.

Whom neither force nor fawning can

Unpin, or wrench from giving all their due.

Whose honesty is not

So loose or easy, that a ruffling wind

Can blow away, or glittering look it blind.

Who rides his sure and even trot,

While the world now rides by, now lags behind.

Who, when great trials come,

Nor seeks, nor shuns them, but doth calmly stay,

Till he the thing and the example weigh.

All being brought into a sum,

What place or person calls for, he doth pay.

Who never melts or thaws

At close temptations. When the day is done,

His goodness sets not, but in dark can run.

The sun to others writeth laws,

And is their virtue: virtue is his sun.