The other day – a cold grey day, the kind of day that makes summer seem as distant as a star – I encountered a woman who stood out. She was cheerful despite everyone else’s winter gloom, and she was wearing a home-made tabard. The tabard was covered in a layer that seemed to be made of tape and clingfilm, and underneath it were little Ukrainian flags, images, facts, and small everyday items like soap. I have seen her before dressed the same way. She stood out, I think, because of her attire but also because of the defiance she radiated – a defiant joy, but also belief that it is worth hoping and acting in the ways we can, even when all the evidence seems to tell us those actions make no difference. The news of Russian’s invasion on Ukraine in 2022 has lost its initial shock power. We are creatures who like stories, and so we like news that has a clear beginning or end. The messy middle can be hard to stick with, precisely because we do not know what comes next or how long it lasts. And so our attention moves on. This, coupled with our felt powerlessness in something so big and distant, can mean it is easy to lose hope, to stop taking action.

But the woman who raises awareness most days in this creative way, with suggestions for what items to donate or how to send funds or how to host refugees, has been making me re-look at hope. Her posture – her insistence on hope as choice – feels life-affirming and countercultural. For a moment, she snaps me out of despair for the world. She faces looks of bemusement and seems to say, if not this, then what?

What keeps us moving forward when the world seems heavy? Where does hope spring from, even in the face of overwhelming odds? Hope, I have learned, has been tangled with humans for as long as we’ve walked the earth. It ensured the survival of our ancestors because it drew them towards a future that might be better than today. It kept them going.

In Greek mythology, Pandora opened a box out of curiosity despite being told not to. All kind of curses contained in the box spilled out into the earth. She wrestled the lid back on but not until it was almost too late. Almost, but not entirely. One thing remained in the box: hope. This myth always brings to my mind memories of visiting a slave fort that still stands on the coast in Ghana. The walls were oppressive, the words above the gate that led to the slave ships were haunting: ‘door of no return’. And yet I learned that there were songs. Spirituals and other songs that passed the time, helped members of different tribes feel connected when they were all shoved together, and conjured hope despite all the evidence to the contrary.

Optimism asks us to sit back and hope for the best; hope knows that we have work to do to bring forth a better future.

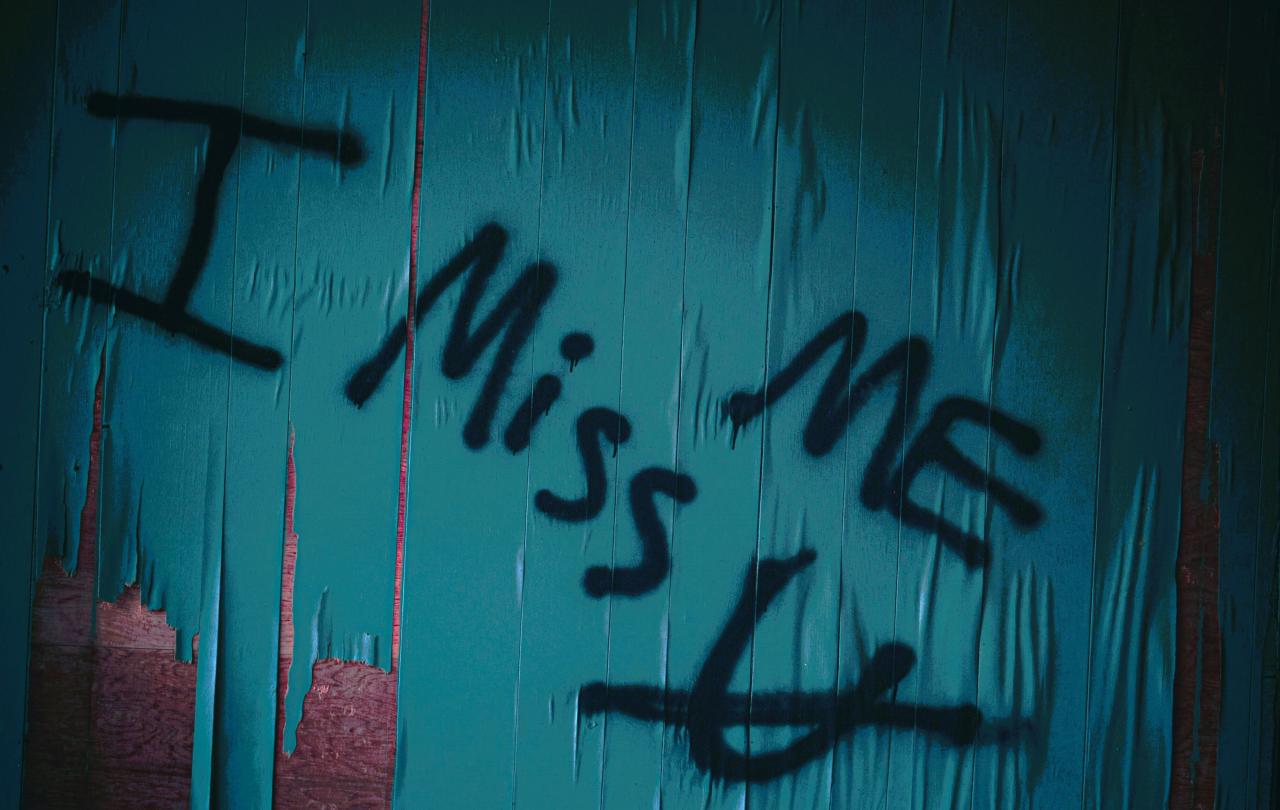

Ideas of hope have been with us always. And yet I find that hope can feel hard to conjure now, staring into the face of an increasingly unknowable and uncertain future: authoritarian leadership that seems to be on the ascendancy, impacts of the climate crisis that are coming into startling clarity, and loneliness that has been declared a global health concern by the World Health Organisation. It is easy to feel that things are falling apart. Faced with these things and more, hope can seem naive, wishful, hard to get hold of.

Perhaps one reason for this is that hope, in the age of the individual, is harder to come by because hope is relational, it cannot exist in isolation. It is transmitted through community, story, and care for others. Those old slave songs sang of hope because, I imagine, people had the reality or memory of each other. Hope said: people have been good, and they will be good again. Hope is insistently communal. It asks us not to bear the weight of the world on our own, but to face each other and distribute that weight via a web of relationship. Perhaps now, accessing a hope that can carry our burdens and our fears means first re-finding each other.

Hope and blind optimism are, of course, different things. Rabbi Jonathan Sacks said that “Optimism is the belief that the world is changing for the better; hope is the belief that, together, we can make the world better.” Optimism asks us to sit back and hope for the best; hope knows that we have work to do to bring forth a better future. And so perhaps that’s why lately, hope has felt exhausting. I’ve worked with communities internationally and locally for two decades on all kinds of projects, always asking, is this how things have to be? How might we imagine and build better? And yet still the climate worsens, inequality persists, bad leaders get into positions of terrifying power. It is easy to stand back and despair, to question, to wonder if all the hard work has been in vain.

Jesus knew this exhaustion. He knew what it was to work, encourage, and love hard, often to face rejection, mockery, and ultimately death. But still Jesus chose to enter into the persistent mess of the world. He chose the day in, day out work of becoming flesh. He affirmed the dignity of the marginalised, calling them into action, knowing that action would keep that dignity alive. He knew that new life would come through suffering, not by denying it.

Strongman authoritarian leaders aren’t the problem, they are a symptom of a society who are divided and not encountering each other well

Perhaps hope is hard too because though it is a posture which faces the future, it also asks that we live with integrity, love, and care right now, in this fractured world. Hope is not writing off the present in favour of some distant time or place. It is not wishing this world away so that we hasten to another one. It says, we can work for a better future, but we should not put off good work until then. That better future will only come if we invite it into our present, whatever the outcome might be. Hope is in living deep and timeless and world building values, even if there are no obvious or immediate results. Czech playwright and former dissident Vaclav Havel who led his nation after the collapse of communism said that

“Hope is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out.”

If a principle is right for the future, it is right for now, even if that requires work. If I espouse values of kindness, love, community, and imagine a future where these things rule, and yet ignore the marginalised, or distrust people not like me, or cut off people I don’t agree with, then my hope for the future is no more than optimism, because I am not willing to do the difficult work of living as if that future were here now.

Hope is turning outwards and living these values with others, even when honestly sometimes it seems easier and more appealing to turn inwards and single-handedly try and fix things — a myth that has grown in our age of individualism, celebrity, and our self-referential rhythms of life.

Hope has lately been asking me to take a Beatitudes perspective on things. In his Beatitudes, Jesus flipped the logic of the world on its head. The last will be first, the poor will inherit the kingdom, the weeping will find joy. Like the Beatitudes, hope asks me to take a different approach. When I look at the world through this lens I find new ways to think. Perhaps, for example, things aren’t getting worse but instead are becoming clear, truths are being unveiled – and so climate change is not the problem, rather, it is a symptom of a greedy economic system in which we are all complicit; Strongman authoritarian leaders aren’t the problem, they are a symptom of a society who are divided and not encountering each other well, and of money and distrust having too big a say in how we govern ourselves. This doesn’t mean we should stop addressing the symptoms, but that we have new possibilities in our scope for action.

Now, as we enter another cycle of — at best — strange politics that is steeped in lovelessness and will have unknowable outcomes near and far, the thing I search for alongside wise voices is hope. And searching for hope means living a good future now, and finding others who can carry both despair and beauty with me. Novelist and critic John Berger said that

“Hope is not a form of guarantee; it’s a form of energy, and very frequently that energy is strongest in circumstances that are very dark.”

So let us call on that energy, that light in the dark today. It is how we build the future.

Join us Behind the Seen

Seen & Unseen is free for everyone and is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you’re enjoying Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Alongside other benefits (book discounts etc.), you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing what I’m reading and my reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief