Genesis Tramaine begins her presentation as part of the McDonald Agape Lecture in Theology and the Visual Arts 2025 by singing ‘Amen’, a gospel song popularised by The Impressions in the 1960s. Her presentation about her art is essentially an act of testimony, such as might be given in a Southern Baptist Church in the USA.

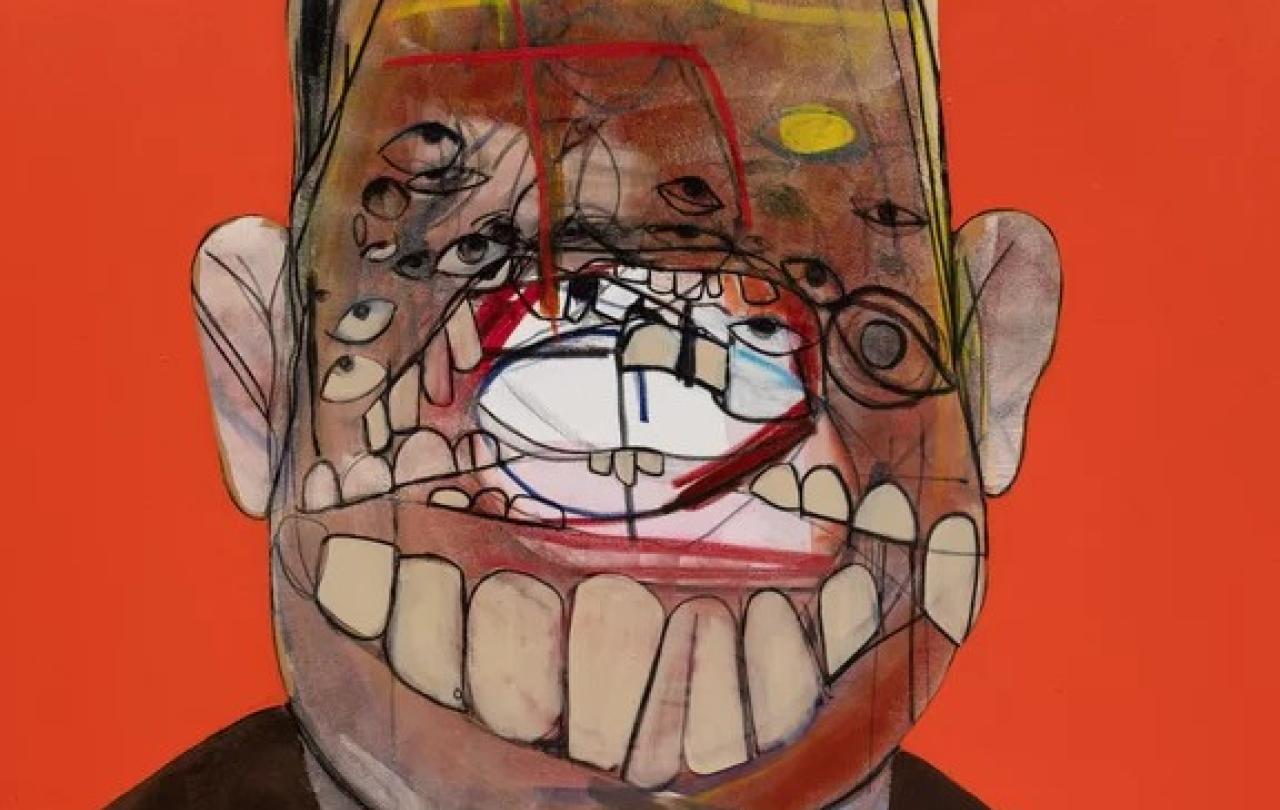

Tramaine is an expressionist devotional painter from the US who is deeply inspired by biblical texts and whose work is held in permanent collections, including the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC. The large expressionist heads she paints are not representational portraits but expressions of spiritual energies and forces within the person, often inspired by and showing biblical figures and saints, as well as church people, family and friends.

She speaks about having met the Gospel before meeting God, as she attended a strict Southern Baptist Church while growing up. She drew from the back of the church and also wrote thoughts and impressions in notebooks. She says that she loved church but that it fell out of place in her life as she grew up.

One day, far from home and needing help, she called her Nana on the phone, who said to seek first the kingdom of God. She found quiet in herself and prayed more, finding herself in conversation with herself. On one occasion, disturbed, she couldn't sleep and was experiencing physical manifestations. At this time, she says, she saw all of herself and surrendered to God. In the morning, she read Matthew’s Gospel - seek ye first the kingdom of God.

The words in the Bible started to make sense to her as a story reading itself to her and she began drawing faces. Her Bible had white images of Christ and Mary, so the words didn't match the images, and this was a spur to paint the women and children of the Bible revealing the beauty of black women in particular. She read the Bible in the King James Version, stopped trying to fit in and found the strength to play with and disrupt narratives. The tools and materials to do this were all one’s that she found in the Bible.

Eyes are our organ of vision, so faces sporting dozens of eyes are those which, like the saints, achieve the greatest insight into the true depths of reality.

Her current exhibition at the Consortium Museum, Dijon, France, is entitled Facing Giants’ and addresses these issues head-on. She has said of the exhibition: ‘I think it’s important that you paint a real narrative, an honest reflection. I don’t think [my saints] look like saints as they have been given to us...[those] were false narratives. The images of saints that we know and that are projected at us are all white with blond hair—and we all know that that is not true.’

She has explained that: ‘These are biblical saints who have faced giants whether those giants are actual giants or giants like fear, love, acceptance or non-acceptance, the giants of facing God and not being accepted, giants of judgments… those who have sat in the mud, if you would, and found a way to persevere. And I wanted to spend as much time as I could with those energies and those narratives, as a tool of self-encouragement and as a tool of encouragement for others.’ She feels these energies literally, speaking of entering the room where she paints with a sense of a whole other people - silent saints – being present with her when she is at the canvas.

While Tramaine emphasises the inspiration of the Holy Spirit in her work, critics have noted her stylistic closeness to graffiti art and she herself has explained that she was familiar with graffiti in her childhood in Brooklyn. Eric Troncy, Director of the Consortium Museum, relates her work stylistically to the expressionism of George Condo, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Willem de Kooning. Tramaine, though, speaks of other influences including Sister Gertrude Morgan, Romare Bearden, and David Hammond. In the McDonald Agape Lecture, she spoke of Hilma af Klimt and Jack Whitten as inspirations, as well as gaining inspiration from the significance of the Iyoba Idia of Benin in Nigerian culture.

One of the distinctive features of Tramaine’s portraits is the plethora of eyes that often feature. Eyes are our organ of vision, so faces sporting dozens of eyes are those which, like the saints, achieve the greatest insight into the true depths of reality. Some more recent images have also featured a plethora of open mouths and teeth. Troncy writes that: ‘Her figures, it seems, have started to smile. To shout, perhaps; to sing—why not?; and to talk—most definitely.’

This is interesting, in part because, when I asked her in an earlier interview about her influences, she began by speaking about her love of gospel music, including that of Jonathan McReynolds and Le’Andria Johnson. She says this Jesus focused music ‘encourages me to praise from the depth of my soul; to paint, let go and trust from that space’. While she’s ‘not quite sure what happens’ then, ‘Black folk say I catch the spirit’. She speaks of losing time as you paint, saying that you can't be present when painting as you have to trust yourself to the process, surrender, and play in the space.

This is, in part, why she began her McDonald Agape Lecture presentation by singing.

Her testimony is essentially simple, direct and profound: ‘I've wanted to be an artist since I was a child. I took my prayers seriously, which means I began to develop a relationship with Jesus Christ, my Lord and Savior … I asked God if I could paint and pray, help and give, as an offering of service for the rest of my life. And the paintings began to mature. I committed to the relationship that painting offers spiritually, in Jesus’ name.’

Support Seen & Unseen

Since Spring 2023, our readers have enjoyed over 1,500 articles. All for free.

This is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you enjoy Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Do so by joining Behind The Seen. Alongside other benefits, you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing my reading and reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief