People have been evangelical about the van Gogh exhibition at the National Gallery. Demand was high, with people sharing membership cards, and the gallery keeping its doors open all night on its final weekend. So off we went, except with a toddler and a baby (not for the late night session).

Along with the disapproving looks at the noise generated, and the security guard telling me I couldn’t have my son on my shoulders, was also the kind lady in her 60s with her large print guide expressing sympathy and empathy. We stayed for about half the time I would have wanted, and even that time was divided attention to put it generously, but it was glorious. Our kids were utterly, blissfully ignorant and had no concentration span for such a high concentration masterpieces. I was also grateful that our baby didn’t join a protest by throwing her purée at the Sunflowers.

It was less of an immersive experience than I might have had in another stage, and I wasn’t following the implicit and explicit rules of a very particular subculture. As a priest it pains me that this is so often the message transmitted by the church and how visitors can feel.

David Cameron wrote in his memoirs about how his first encounter with the late Queen was as a schoolboy reading at a carol service, with the monarch in the front row. When he finished the reading, he walked off, before realising he hadn’t said the right words - 'thanks be to God' and then he panicked and swore. This can often reflect our impression of church: you’ve got to be neat, make sure you say the right thing, don’t say the wrong thing - with this authority and power figure there near you watching with a keen eye that you do everything just so. And that's before you consider how weird it can be to participate in a public meeting in a church in a format called a service.

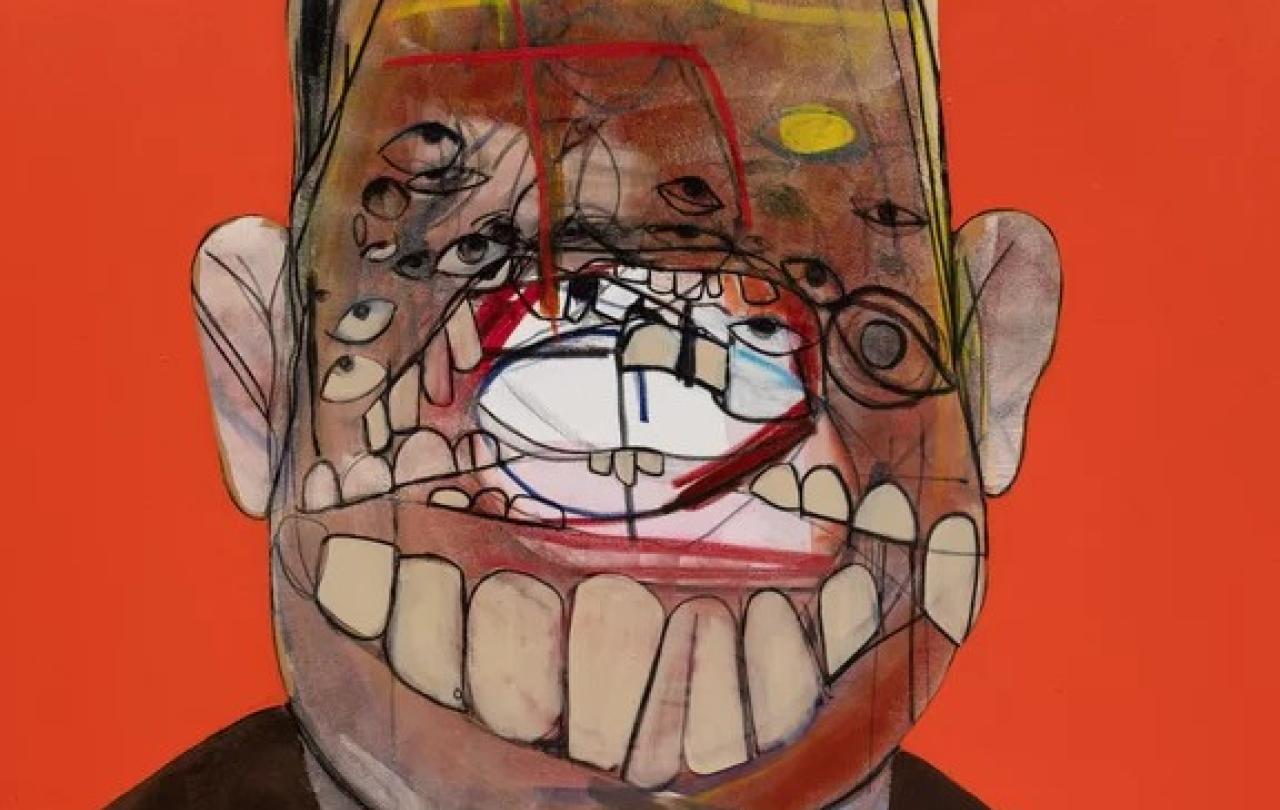

A church is not a gallery with perfect pictures. Lucian Freud said of the National Gallery: 'I use the gallery as if it were a doctor. I come for ideas and help.' Church should be a place where we are inspired, to have our 'hearts lifted' in the words of Thomas Cranmer, but also we would do well to think of it it more like a hospital. Where our right of entry is our weakness and need for help. Van Gogh himself said that 'Art is to console those who are broken by life.' Church should be a place where more than observing a master's work from a safe distance, we are in the presence of a master who made us and wants to restore us, all the while finding our company amusing and enjoyable.

It mightn't feel like the hottest ticket in town, but I regularly hear people finding courses like Alpha a refreshing way to taste the essence of what church can be: where it is made explicit that no questions or thoughts are off limits, and you don't have to worry about standing up or sitting down at the right time. Belonging isn't performance art.

And if we have the courage to come close to the colour and the texture - we find the possibility of understanding a little bit more about the artist behind it all.

Join with us - Behind the Seen

Seen & Unseen is free for everyone and is made possible through the generosity of our amazing community of supporters.

If you’re enjoying Seen & Unseen, would you consider making a gift towards our work?

Alongside other benefits (book discounts etc.), you’ll receive an extra fortnightly email from me sharing what I’m reading and my reflections on the ideas that are shaping our times.

Graham Tomlin

Editor-in-Chief