Do you, like me, ever look around and ask yourself:

“What, of the things I see as normal now, will I realise were very wrong in 50 years?”

There were times in history when a huge proportion of the UK population saw no issue with forced labour and slavery. Sexism and even sexual assault were par for the course in corporate environments. Forcing young pregnant girls to give their babies up for adoption was considered “for their own good”. The list goes on.

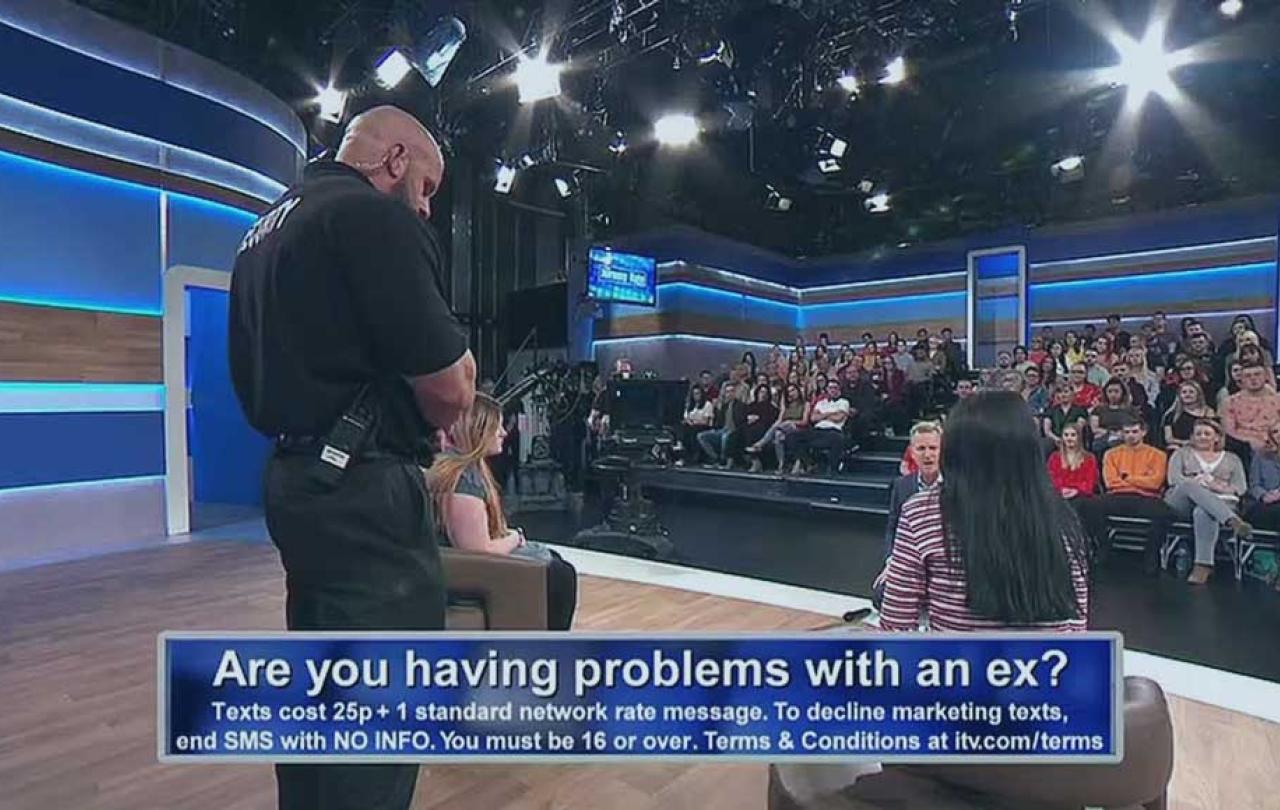

Talk shows, I believe, are now transitioning into the category of: “I can’t believe we thought that was OK.” The term “talk show” is used for two different formats; first the Parkinson style celebrity interview programmes, often billed late in the evening on the weekends and attracting big name guests. Then there’s the other kind – the one I’m talking about. The Jerry Springer, Jeremy Kyle audience shows where, often vulnerable, guests are invited to resolve some sort of conflict in front of a baying audience with a taste for blood.

When the “King of the Talk Show” Jerry Springer passed away last month at the age of 79, I couldn’t help but hope the TV format he made so famous would die with him. Brutal, I know. But it really is for the best.

The first episode of Jerry Springer aired in the States in 1991. He may have been the most famous, but he wasn’t the first. The Sally Jessy Raphael Show launched in 1983, it tackled tough tabloid issues like teen pregnancy and extreme religious views. Sally’s firm but fair, maternal style of leadership attracted a loyal fan base.

Outrageous content led to the sort of high viewing figures TV execs are happy to sacrifice people’s mental health for. So, the show went on.

Then in 1987, the launch of Geraldo, saw the daytime talk show make further waves. Fronted by journalist Geraldo Rivera, it was the show that inspired people to coin the term “trash TV”. Producers put virtually no effort into screening their guests, even hosting one show with Klu Klux Klan members on the same stage as Black and Jewish activists. This descended into an almighty brawl that included guests, audience members, crew and the host who left with a broken nose after someone hurled a chair at his face. You’d think that would be enough to call it off. You tried. It was chaos. Time to take your ball and go home, right? Of course not, the outrageous content led to the sort of high viewing figures TV execs are happy to sacrifice people’s mental health for. So, the show went on.

1991 was a big year for the tabloid talk show concept, with the introduction of a number of big names; The Maury Povich Show, The Jenny Jones Show, The Montel Williams Show and most famously Jerry Springer. They were later joined by Hairspray’s Ricci Lake whose iconic addition to the daytime TV scene was aimed at a younger crowd of “stay-at-home-moms”.

The Jerry Springer Show started off as a political talk show, but poor ratings encouraged producers to continuously adapt the model. In the mid-90s they landed on the salacious topics that it became famous for. Themes like incest and adultery were commonplace. Jerry featured a man who claimed to have married his horse, a woman who was pleased that she had cut off her own legs and a mother-daughter dominatrix duo. The bestiality episode has now been banned, but I reckon I could use my journalistic prowess to track down the others if I felt so inclined. Fortunately, I don’t.

The format gave guests an opportunity to publicly talk about their feelings, something that until that point, had only been open to the middle classes.

Meanwhile, us over the pond had finally caught on. If there were ratings to be boosted in America, there were ratings to be boosted in Blighty. Vanessa Feltz was one of the first to introduce the genre to the UK in 1994 with her self-titled show. The format gave guests an opportunity to publicly talk about their feelings, something that until that point, had only been open to the middle classes. People were excited by the show. Vanessa and her crew went on the road to invite real people to tell real stories. She was warm and allowed people to feel safe in opening up. While it wasn’t perfect, the programme was genuine in its desire to support those who spoke out about issues like domestic violence, eating disorders and sexual abuse. When Vanessa moved to the BBC in 1999, her ITV morning slot was filled by Trisha Goddard. Incidentally the BBC’s The Vanessa Show was cancelled later that same year after The Mirror newspaer revealed some of the guests had been paid actors.

It didn’t matter by then, because there was a new UK chat show queen and it was Trisha. Again, Trisha insisted that she was the to support – not to condemn. As the show grew in popularity, the producers began chasing ratings and the topics got increasingly incendiary. I had a friend who went on with his girlfriend. He was a former SAS officer and was having relationship issues with his glamour model partner. After one particularly vicious argument between the pair, he tied all her clothes in military grade knots. She wasn’t able to free her garments so was left without a wardrobe. Despite Trisha’s intervention the couple didn’t stay together.

It's a story we hear all the time in the media. If the audience keeps clicking/watching/streaming it, the producers will keep making it.

People lapped up the opportunity to peak from behind the curtain into the messy lives of others. One former producer who worked on both shows spoke to Eastern Daily Press about Trisha:

“It certainly didn't start out as a show designed for people to watch and laugh at others: it wasn't cruel. Over time, it did change as people's expectations changed. At the end of the day, the broadcaster is always chasing ratings.”

It's a story we hear all the time in the media. If the audience keeps clicking/watching/streaming it, the producers will keep making it. And it goes on and on. A tawdry game of one-upmanship where both the audience and producers feel vindicated as they blame the other for the problem. The serpent is eating its own tail and growing all the fatter in the process.

And then came Jeremy Kyle. What Jerry Springer did in the States to escalate the talk show, Jeremey Kyle did for the UK. Jerry Springer capitalised on the most sexual and depraved stories he could find and then put people in a ring to fight it out (their clothes hopefully coming off in the process). While Jeremy Kyle’s tactic was to belittle. He chastised and shouted. He told people to “get a job” and shamed them for accessing state support. He was judgemental, pious and cruel. The aim became to mock and humiliate, not to encourage and support. And all this came at a time where we as a society were poised and ready to take the mick out of the working classes or “chavs”. We lapped it up.

We weren’t “loving our neighbour”, rather loving their misfortune. Way back in the heyday of the Roman Empire, a cultural activist called Paul, wrote to some Christians living in the heart of the empire, Rome itself. He wrote:

“Live in harmony with one another…do not repay evil for evil…if it is possible, so far as it depends on you, live at peace with everyone.”

But instead, we made a spectator sport out of domestic conflict. The audience kept growing as we lapped up the misfortune of others, often those from disadvantaged backgrounds. We disregarded the biblical proverb that advised:

“Do not gloat when your enemy falls; when they stumble, do not let your heart rejoice” (Proverbs 24:17)

in favour of full audience jeering and whooping in the face of another's failure. When I first started working at The Sun in 2016, it was my desk who watched and reported on Jeremy Kyle. We pulled the post interesting segment from the morning show and wrote it up into a tabloid real life story. They are all much the same; a paternity test here, a cheating scandal there. But one in particular sticks in my mind when a guest had come on because they were desperate to work out who had defecated on a plate and put it in the fridge. Brilliant.

The show was cancelled after 14 years on the air and more than 3,000 shows because of the suicide of a participant who failed a lie detector test. Steve Dymond, 63, had been told to come off his anti-depressant medication in order to take the polygraph. He failed the test and was berated for “cheating on his partner”. He couldn’t handle the shame and the prospect of losing his relationship, so he ended his life.

Perhaps these shows started out as platforms for healthy conflict resolution, but that’s not what we, the general public, wanted to watch.

Since coming off air, countless horror stories have surfaced from behind the scenes on the famous show. Former production staff admitted that guests were so hard to come by that they weren’t performing the proper checks before signing them up. They also explained that they would keep guests separate and lie, telling them the other had said awful things about them, before sending them on stage for the confrontation. And perhaps most horrifically to my mind, as a recovering drug addict myself, they told guests hoping to be given rehab treatment that they were competing with other families for one bed in an expensive facility. Desperate addicts were told Jeremy had to think they were the worst case in order to qualify for care at the life-saving facility. When in fact, there was no restriction on places.

Perhaps these shows started out as platforms for healthy conflict resolution, but that’s not what we, the general public, wanted to watch. We wanted the drama. In short, we wanted the poo in the fridge. Thankfully the genre has petered out, both here and in the States and people are now looking back at previous episodes saying: “Did we really think that was OK?”

Prior to his death on April 27, 2023, Jerry Springer did issue an apology for his show and its wider effects. Jeremy Kyle has not, although he did explain in an interview in 2021 that his mental health had plummeted after the show was cancelled and that he felt he was scapegoated in the process.

The grim format has, for now, been relegated to the archives but if there is one lesson I can encourage us all to take from our unfortunate dalliance with tabloid talk shows, it’s to stop fuelling the beast. We may not be showing our support to Jeremy Kyle anymore but there are other topics that we are insatiably consuming despite being sceptical about their suitability in a loving society.

Bored of articles about Harry and Meghan? Stop clicking on them.

Appalled by the unrealistic body image or hook-up culture of reality TV? Stop watching it.

If it doesn’t feel right, good, kind or true – distance yourself from it.

The fact is, you can always find something salacious and titillating if you’re looking for it. There’s always a poo in the fridge. But instead let’s do what Paul also suggests,

“Finally, brothers, whatever is true, whatever is noble, whatever is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is admirable--if anything is excellent or praiseworthy--think about such things.”

We would have put Jeremy Kyle out of business a long time ago if we’d been sticking to the sage advice of scripture.