Most summers we go on holiday to Cornwall in the west of England. One of our favourite walks is across a rather smart seaside golf course, with manicured greens, tidy fairways and well-dressed golfers. Just behind the 11th tee is something you don’t usually expect to find on a golf course: a church. It’s a tiny place, with a small crooked spire and a low slate roof, built of ancient stones weathered by centuries of wind and saltwater. The inside smells of damp hymnbooks and a faint whiff of candle wax, a few memorials to villagers who drowned in the seas nearby, and usually, some flowers carefully placed to give the building a sense of life and colour. Its origins go back 1500 years, supposedly built on the site of a cave where an early Christian hermit called Enodoc used to live and pray.

Built near a beach, over the years, wind-driven sand has built up banks around the church which give it the appearance of sitting in a large hole. In fact between the 1500s and the 1800s, the church was virtually buried under sand dunes. During those years, the vicar and the parishioners could only enter the church through a gap in the roof. In 1864, the church was dug out and restored, and it still holds services to this day, as golfers wend their way past, cursing after another missed putt.

'The buildings kept standing through winter storms, mounting sand dunes, reformations, civil wars and revolutions.'

Year after year for fifteen centuries, people have gathered in that building to pour out their hopes, fears and dreams to God in prayer; husbands and wives made life vows to each other, baptised their children around the small worn font; people took bread and drank wine at the rickety wooden altar and buried their dead in the graveyard surrounding the building. Some of those people had the fierce, intense, focused faith of the hermit who originally prayed on the site. Others had a more uncertain faith that flickered rather than burned brightly, but still was a guiding light for their life. Meanwhile, the buildings kept standing through winter storms, mounting sand dunes, reformations, civil wars and revolutions, and provided a continuity that held together the changing fortunes and moods of that local community for a millennia and a half.

Walking past this minor architectural miracle, I’ve often asked myself the question why people bothered to build a church in such a remote and awkward place, and why such efforts have been made to maintain this tiny structure, which can only seat around 40 people even when jam-packed full.

'This building stood, and stands, for a way of life, and a view of the world that sustained people.'

The answer is that this building stood, and stands, for a way of life, and a view of the world that sustained people in small communities like this, and countless larger ones – towns and cities - for around 2000 years. And it’s not just here. Wherever you go in Europe, when you enter a town or village, somewhere in the heart of that community will be a church. Some are grand, opulent affairs, built by some local grandee eager to show off their devotion, or sometimes, let’s be honest, their wealth. Others, like the one in the golf course, are small, humble, ramshackle structures, lacking in any great architectural merit, but whose stones breathe the love and devotion of the generations for whom that building was the anchor of their lives, the place where life began and ended, and where most significant events were commemorated in between.

These days, many of these churches are struggling to stay open. Regular churchgoing has dropped off in many parts of Europe, and many of these village churches in particular are slowly decaying. It’s partly a result of the general decline in community activities - political party membership has declined significantly, many local pubs and cinemas have closed, and people don’t join things as much as they used to. But at the same time, many people no longer believe what their ancestors did, and so church seems a strange blend of general niceness with some religious mumbo-jumbo that doesn’t really make much sense anymore. Yet many people still celebrate significant life events in churches. Despite the decline in regular church attendance, most people still want weddings in churches, many get their babies baptised, and ask the local vicar to conduct the funerals of their loved ones. There is still something - a sense that these places, and the connection with transcendence that they offer - are places you go to at moments of extreme joy or sadness.

Those people in the past were not stupid. Christian faith held together communities and whole nations across Europe for centuries, not because nobody thought hard about it, but because it gave a framework for living that made sense to people, and enabled them to manage and make sense of their lives. It met the needs of the simplest villagers and the most sophisticated and intelligent philosophers. Of course today we are much more technologically advanced and scientifically knowledgeable than they were. However we still look into a dark night sky and marvel at our smallness in a vast universe just as they did; we still cry agonising tears when we lose our friends and family, or when a relationship breaks up, just as they did; we too ask questions about the meaning of life, freedom, suffering, just as they did. The science may have changed, but human nature does not change that much. The questions we ask are remarkably similar to the ones that our ancestors struggled with in the past.

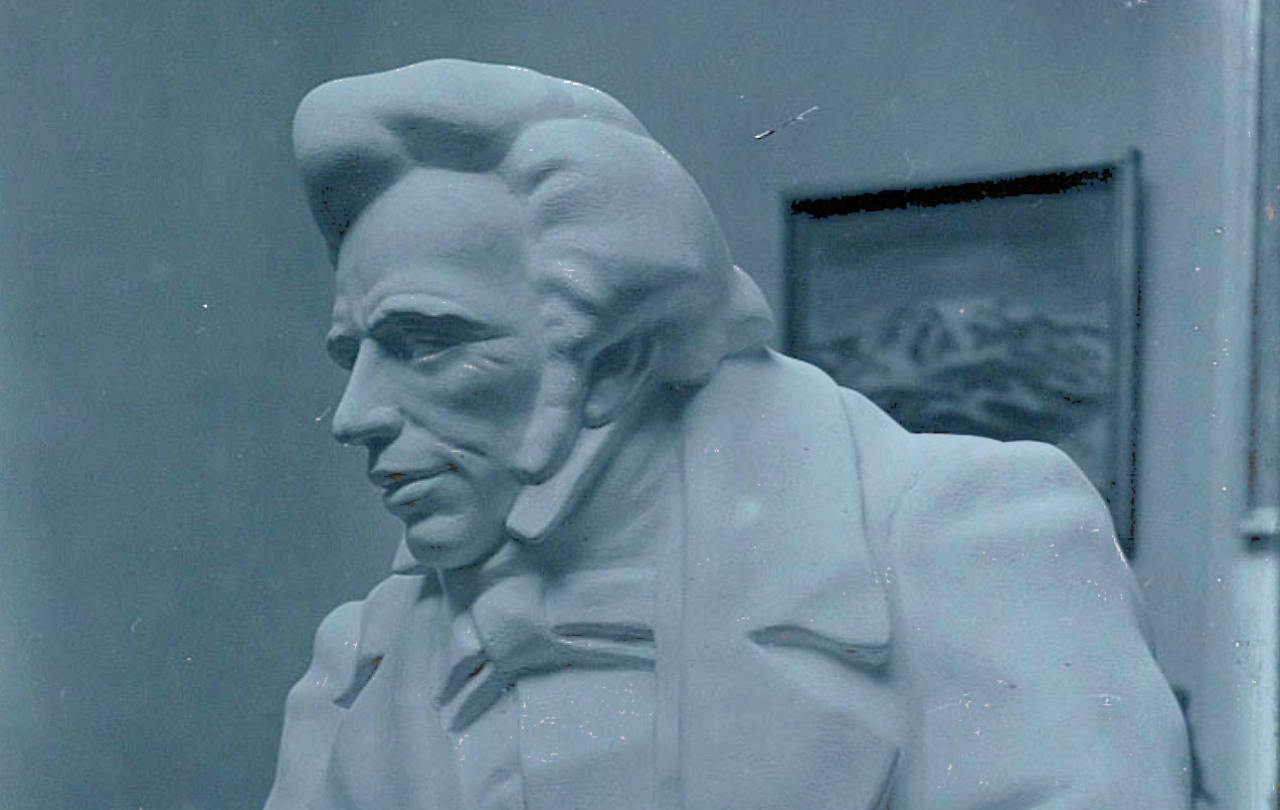

To get a sense of the sheer power of the Christian story, and the way in which it shaped the lives of millions, just walk into any art gallery, and look at just about any section before the 18th century. Many of the paintings and sculptures will be direct references to the stories of the Bible, and even the ones that aren’t often have all kinds of subtle references to Christian belief hidden deep within. Or take time to wander around one of the many mediaeval cathedrals that are dotted around biggish cities across the continent, and ask yourself why people designed structures that they knew they would never see because they took more than a lifetime to build.

We have laid aside this heritage in a comparatively short period of time. People in the west often look to eastern traditions, mainly Buddhist, whether of the full-on type, or the gentler forms of mindfulness, because they seem to offer a pathway to peace and tranquillity as well as a faint whiff of the exotic and tantalising. And yet right under our noses lies a deep well of wisdom that inspired our greatest architecture, our finest works of art, and our most soaring and spine-tingling music, and, to those who have discovered it, still claims to offer peace of heart, a sense of fulfilment and meaning, and an unshakeable underlying note of joy to life.

The problem is that we haven’t really found anything to replace it. As Julian Barnes wrote, in the first line of his book on death, Nothing to be Frightened of:

“I don’t believe in God, but I miss him.”

Our world has changed a great deal - in fact it doesn’t just change, but changes more quickly as each decade succeeds another. However in quite properly leaving behind some of the things our ancestors took for granted, such as slavery or the inferiority of women, we have at the same time lost hold of the central story that gave meaning to the lives of countless people who went before us, and which could still make sense of our lives today. Like the proverbial baby and bathwater, in moving on from the old, we have left behind something immensely valuable which could make all the difference to our lives today.

The well-known author C.S. Lewis once said:

“I believe in Christianity as I believe that the sun has risen: not only because I see it, but because by it I see everything else.”

Christianity, like any other creed, makes sense, not just on its own terms, but if it makes sense of everything else. Christianity offers a kind of counter-cultural wisdom to many of the things we take for granted in our world, things which if we carry on living that way, will destroy us and this precious planet which is our home. It offers a way of life that is much richer, fuller, more disturbing, costly yet utterly worth living – a life where, like that ancient Cornish saint, and those who worshipped in the building named after him, we learn the most fundamental skills about how to live together in a world we did not make.