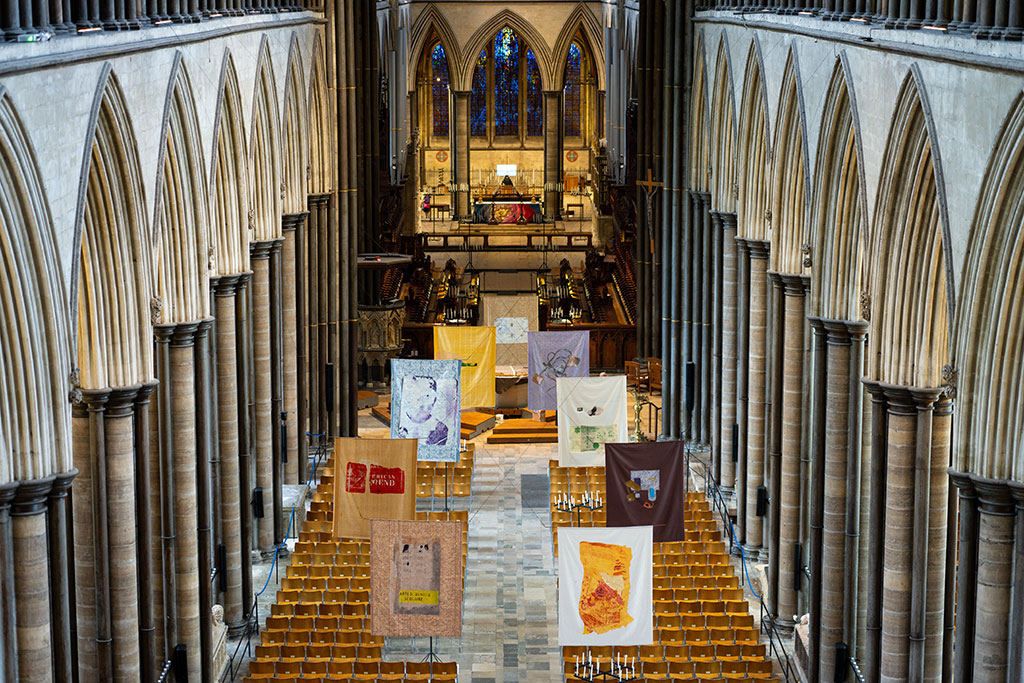

Hung in the central aisle of Salisbury Cathedral and reflected in the still water of William Pye’s cruciform font are a series of textile paintings by Shezad Dawood depicting objects recovered from the seabed of the Mediterranean.

Led by Professor Cristina Cattaneo, a team of forensic anthropologists from the Laboratory of Anthropological Forensics (LABANOF at the University of Milan go out with UN rescue teams when ships have sunk or capsized on the journey to Lampedusa and recover the objects and artifacts (as well as human remains). They do so, to create an archive whereby relatives can track missing family members. Unlike wars and natural disasters, there is no established protocol to deal with immigration deaths but, by its interventions, LABANOF is helping to potentially bring a protocol into being.

As seen at Salisbury, Dawood’s Labanof Cycle ranges from a pinch of earth wrapped in a twist of cling film to a passport and a faded photograph. Each of these textile paintings document a life and a journey in tribute both to lives lost and those that were saved.

Dawood became aware of the work of LABANOF through an article in the New York Times and reached out to them while preparing for an exhibition to coincide with the 57th Venice Biennale. As a result, he met with Cattaneo in Milan and she generously gave access to the archive. Dawood recalls:

“It was a shock to actually be confronted with those objects and be in the room with them. I really wrestled with whether it was appropriate to make work in response to those materials. One of the things that decided it for me, when I went away and sat with it, those objects made all of those lives so apparent to me and that was the shock. It transformed refugees and migrants from a statistical basis to something very human. The fact that I was crying looking at the material was what was important in bringing the humanity back to our fellow humans. There’s something very sad, and almost industrial, about viewing our fellows through the prism of statistics and othering them or demonising them as somehow threatening.”

Kenneth Padley, Canon Treasurer and Chair of the Cathedral’s Arts Advisory makes connections between these works and the themes and stories of Advent and Christmas, saying:

“This exhibition is a timely reminder, amid the anticipation and excitement of Advent and Christmas, that Jesus and his family were refugees and were being persecuted.” In these seasons, we recall the vulnerability of Jesus, Mary and Joseph, forced by political order to travel from Nazareth to Bethlehem and then by fear of King Herod from Bethlehem to Egypt."

“None of us straightforwardly belong anywhere, however long our forebears have sojourned there, and none of us abide long on this earth”.

Sam Wells, Vicar of St Martin-in-the-Fields, has noted that we are all “strangers and pilgrims on earth”, and that “God is the one who comes to us like one unknown” being “in the world, but the world received him not”. He suggests that it is by the way we receive this challenge, that “the Christian community demonstrates who we realise we are and who we believe God is”.

More than this, he argues that the Bible itself is founded on six journeys, all of which have a bearing on themes of migration: “Jacob and his entourage migrate to Egypt in the midst of famine. This is an economic migration, but really it’s a journey of survival. Moses and the children of Israel migrate from Egypt to the Promised Land. They leave as refugees to flee slavery. They take 40 years to reach their destination, and, when they get there, they face a very hostile environment indeed. Judah loses a battle and is displaced 500 miles to Babylon. There, as Daniel shows, exiles play a vibrant role in public life, and bring unique qualities, represented by the ability to interpret dreams. Jesus travels from Galilee to Jerusalem. He’s living during the occupation by an invading power, Rome. Finally, Paul migrates from Jerusalem to Rome. He’s searching for legal protection in an empire where citizenship transcends geography.”

His conclusion is that “most of what we’d today call migration is in the Bible, and it’s through migration, not in spite of it, that revelation occurs”. As a result, we don’t get Judaism or Christianity without migration. He adds that “the greatest migration of all is of Christ from heaven to earth and back” and the statement that “Here we have no abiding city” “is an announcement that we should consider our whole lives as a season of migration, because we are transiting through earth to find our true home elsewhere”. As a result, “None of us straightforwardly belong anywhere, however long our forebears have sojourned there, and none of us abide long on this earth”.

The exhibition at Salisbury Cathedral is a small part of a large body of work begun when Dawood was working on two separate projects; one which involved research about democracy, the other about the oceans. The title of the exhibition refers to Leviathan, a 1651 text by the philosopher Thomas Hobbes which takes the sea monster described in the Book of Job as a metaphor for the state.

“What’s been quite shocking has been that things people told me we might witness in 10-15 years, I’ve seen happen in five”.

Dawood’s Where do we go now? is a polychromatic painted sculpture, depicting sailors in a small boat encountering a whale, that is inspired by engravings and illustrations from Jonathan Swift’s A Tale of a Tub, a 1704 pamphlet on the nature of legitimate government that was written in response to Hobbes. The whale represents the State, which threatens to destroy the vessel, prompting the sailors to throw a barrel (or ‘tub’) representing their labour (or ‘capital’) overboard to distract it. With figures representing refugees and a UN rescue worker in Dawood’s sculpture being placed within the Cathedral’s 1215 Magna Carta exhibition space, this work prompts visitors to consider the legacy of Magna Carta and the rights and freedoms of refugees.

Dawood has said that the exhibition is “an exciting opportunity to bring some of the key questions I’ve been asking of climate, migration and our shared humanity … at a time when a renewed sense of sharing and purpose is urgently needed.” In the light of such thinking, Beth Hughes, Salisbury Cathedral’s Visual Arts Curator, suggests that,

“Shezad’s exhibition is a powerful reminder of how we are all connected to each other, and to the natural world … [focusing] the mind to help us think about how we might be part of the solution, to make a better world for ourselves, our loved ones and all of humanity.”

Much of Dawood’s work is concerned with “world-building” and “imagineering”, something that developed from a “youthful love of science fiction, speculative fiction” which he found to be “a really useful space for philosophical dialogue and imagination”. Then, as “confidence and practice grew, I found through conversations with other artists, writers, academics, that we could have these conversations and start to imagine possible or plausible futures as a way to reflect on some of the issues of our time”.

One result has been the Leviathan Cycle, a ten-part film series exploring unexpected narratives that connect the most urgent issues of our times: climate change, migration, and mental health. When he began, he experienced surprise or disbelief at what he was trying to do “which was to imagine the world in 20-50 years’ time” in order to highlight the urgency, “because it felt like we didn’t have much time in which to change course”. He was primarily “thinking about what the immediate fault lines were and how they could deepen and darken in our lifetimes or just beyond”. As he started going out talking to scientists, particularly those working around climate, “there was something quite interesting about this 20-50 year’ timeframe, because their predictions were in that range”. However, “what’s been quite shocking has been that things people told me we might witness in 10-15 years, I’ve seen happen in five”.

How can we find new reserves of empathy and understanding for the difficult circumstances we are going through in our world?”

The Cycle follows the journeys of a cast of characters who are the survivors of a cataclysmic solar event in order to reflect on the systemic crises within our biosphere and imagine where we might end up if we fail to gain a deeper understanding of the intersections between fields of knowledge and ways of living, across and between human and more-than-human ecologies. The first five films imagine a dystopian future while the latter five - of which the latest, Seven and Eight, are on show here – explore “ways to navigate and negotiate this future with each other, with our government; ideally, a new social compact that’s not just human but extends beyond the human”.

Episode 7: Africana, Ken Bugul & Nemo, in the North Transept, takes the viewer on a journey through the Mangroves of Senegal which speaks of our interconnectedness where both science and the imaginary dovetail into a possible, collective future. Episode 8: Cris, Sandra, Papa & Yasmine, in Trinity Chapel, charts an embodied, spiritual, and ecological journey along an age-old Guarani path linking the Brazilian Atlantic Forest to the sea.

The wider Leviathan project from which the work on show in the Cathedral is taken, is the culmination of conversations Dawood has had with a wide range of marine biologists, oceanographers, political scientists, neurologists, and trauma specialists. This approach is typical of his practice, which often involves collaborations with groups and individuals from different disciplines that are transformed into expressive artworks.

The Leviathan Cycle itself has become a large community of scientists and collaborators around the world. The collaborative experience has broadened Dawood’s horizons in terms of how he thinks of the subjects of his work: “It’s not just a protagonist in a film or an artefact, it’s each of these scientists’ individual area of study that they’ve devoted a huge part of life and time to, and so it creates this huge web of obligation. It’s part of empathy and reciprocity, it’s how we work with others and try to do our best.”

As a result, he says: “There’s a debt to generations beyond us. They only stretch us just a little but we become better human beings by doing so. I think it’s also important to go beyond the human as well and stretch our empathy to include the non-human – animals, plants, algae – they’re all systems of which we are part and which we interconnect with in surprising ways. It’s something that I’ve become more actively aware of through this body of work. It just feels pivotal.”

His hope “is that the exhibition encourages visitors to think about ourselves as one humanity”: “My engagement with the topics of climate change and migration are driven by wanting to see a new set of ethical standards established for the world. How can we find new reserves of empathy and understanding for the difficult circumstances we are going through in our world?”

As we come to the end of 2023 and think about the coming new year and further into the future, the beauty of this exhibition and of Dawood’s work is that, as Beth Hughes notes, it “draws you in to explore some of the big questions facing humanity today”. World events in 2023 “have shown us how important it is to care for displaced people and the importance of looking after our natural world”. Kenneth Padley says, “The overriding message is a call to action before it is too late”, which is why the exhibition is prefaced with a verse from St Paul’s letter to the Romans that simply states, “Live in harmony with one another”.

Leviathan, An exhibition by Shezad Dawood at Salisbury Cathedral, 28 November 2023 – 3 February 2024.