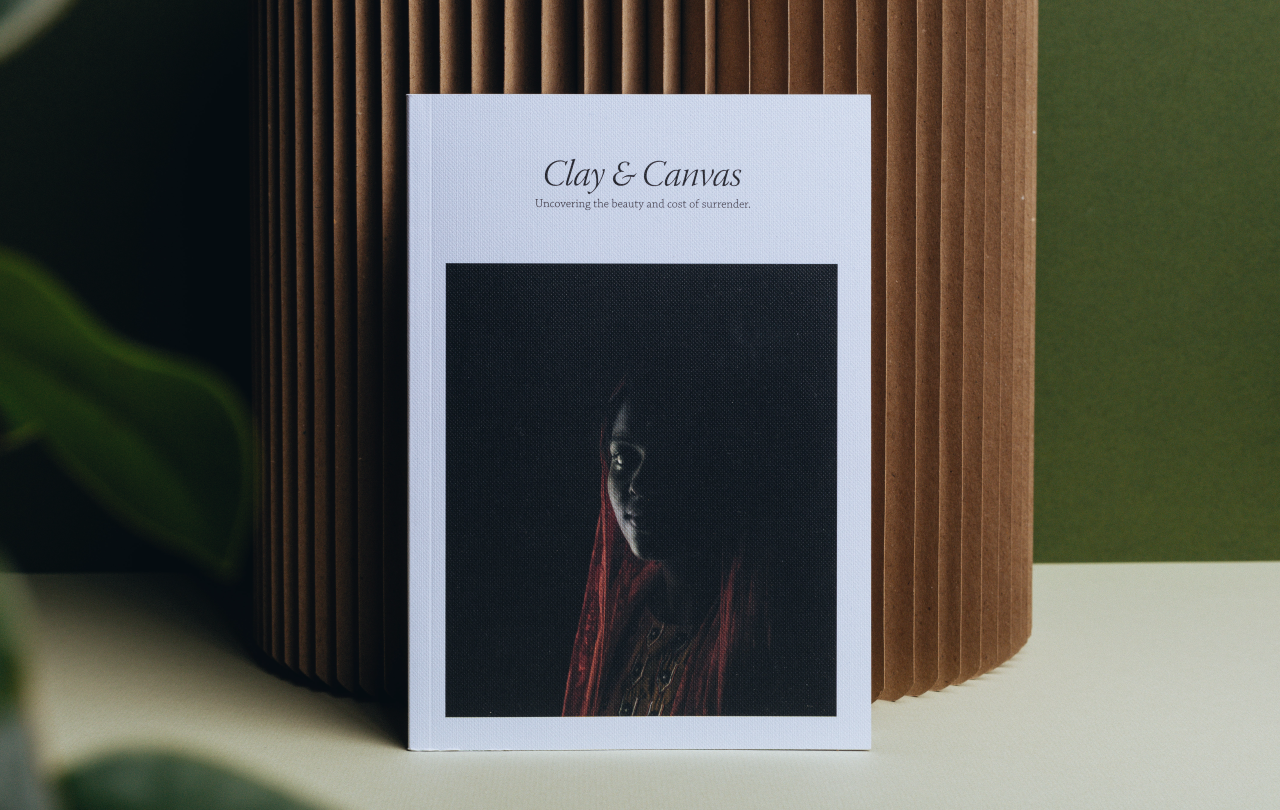

In 2018, in the Houses of Parliament, Hannah Rose Thomas displayed a collection of radiant portraits she had painted of Yazidi women who had escaped ISIS captivity. She did this to bring their ongoing plight to the attention of the Government. In 2019, at the London Riverside Development, three photographers (Chris de Bode, Abbie Trayler-Smith and Nora Lorek) used their photographs to powerfully tell the story of the hunger crisis in Sudan, Liberia, and the Central African Republic. In 2021, a 3.5-metre-tall interactive puppet of a 10-year-old Syrian girl named Amal was walked from Turkey to Kent, and in so doing, gave the world a glimpse of what such a journey entails for thousands of refugee children. And in 2022, the advocacy group, Open Doors, published a striking book entitled Clay and Canvas, which compellingly tells seven stories of individuals who have faced un-imaginable trauma because of their belief in Jesus.

While these projects were created by different people, at different times, highlighting different situations, it seems to me that the powerful impact of all four artistic offerings is twofold. Firstly, they each force us to move beyond numbers and statistics, inviting us to come face-to-face with the humanity behind the headlines. And secondly, the utter beauty with which these pieces have been both created and curated hints at the startling beauty that can be found in the midst of pain. The glimmers of light that are ever present, even in the darkest of contexts.

This is most certainly the case with Clay and Canvas.

Its strikingly minimal aesthetic ensures that it can comfortably sit alongside the most classic of ‘coffee table books,’ but instead of being filled with recipes, interior decoration inspiration, or the complete lyrical works of Paul McCartney, this holds within it stories that will simultaneously break and inspire its reader’s heart.

There are around 360 million people in the world who are currently under some sort of threat because of the Christian beliefs that they hold, and this book tells just seven of those harrowing stories.

It introduces us to Baheer and Medet, two friends who played together as children, but now find themselves in a torture chamber. One of them is being electrocuted because of his Christian beliefs, while the other is looking on at the torture of the friend that he himself had reported to the authorities. Both are utterly terrified.

We also meet Rebekah, Eti and Ratina as they are thrown into the back of a police van, sentenced to five years in a high-security prison for telling children about their belief in a man called Jesus.

And then there’s Kirti, who is being continually hounded by a violent mob, her body repeatedly broken and battered by their sheer anger at her refusal to deny her faith.

These stories are an afront to the comforting habit one may have of disassociating individual realities from vast statistics.

These stories don’t give their readers the blissful luxury of ignorance. They are an afront to the comforting habit one may have of disassociating individual realities from vast statistics, of regarding this epidemic of violence as some sort of faceless or nameless phenomena.

Rather, readers are brought face-to-face with the detail of religious persecution. We are shown the thought-processes of a man on the brink of death, we are walked through the moment-by-moment decisions of a person attempting to flee for their life, we are exposed to the agony of three women being separated from their children.

The writing is heart-wrenchingly powerful, the stories its telling, infinitely more so. This is certainly not your average ‘coffee-table book.’

As well as the written stories, there are photographs of these persecuted individuals dotted through-out the book. Readers are not only told their stories, they are also shown their faces. These pictures serve to remind us that this discrimination isn’t happening to people who resemble cinematic-style heroes, it is happening to husbands, wives, daughters, sons, neighbours, friends, mothers, fathers.

2023 is the most dangerous year to be a Christian on record, it is integral to the increasing number of people who are losing their right to hold their beliefs that this reality is continually, and indeed creatively, amplified.

And yet, as noted earlier, the darkness of these stories is not devoid of glimmers of light. There is a distinct thread of redemption that is weaved through this resource, and indeed, these people’s lives. The beauty is found in the forgiveness shown by those who have been betrayed, the hope found by those who have nothing else to hold onto, the ‘gentle, defiant glow’ of those who are stubborn in their selflessness – all of it all the more staggering for being completely true.

This book presents its readers with a costly kind of goodness. A truly counter-cultural form of beauty. If you sit with it long enough, it will begin to chip away at the modern and ever-so-Western tendency we have to consider pain and beauty as forces that are mutually exclusive.

Art, in its various forms, is one of the most powerful tools we humans have, and that is never more evident than when it is used to communicate circumstances with a depth that statistics alone could never reach. Clay and Canvas is certainly one such example.

Clay and Canvas has been produced by Open Doors in Partnership with Something More Creative